Grunts (67 page)

In Iraq, by 2005, the Americans were deeply enmeshed in this kind of desperate, deadly counterinsurgent war. They often felt, and acted, as though they were grappling with phantoms in a pitch-dark room. In spite of Fallujah and the successful January 2005 elections, the insurgency was growing stronger and the American death toll was rising in Iraq. Commanders were finding that they had nowhere near enough troops, particularly of the infantry variety, to maintain stability in their areas of operation. “The lack of Army dismounts . . . is creating a void in personal contact and public perception of our civil-military ops,” one general stated. Somehow, a ragged ensemble of third-world insurgents was withstanding the might of the world’s leading military power.

The soldiers were now paying a steep price for the catastrophically wrong ideas their leaders had embraced about war. The flawed 2003 Rumsfeldian vision of a shock-and-awe, techno-rich, lightning-fast war in Iraq had given way to an unglamorous, complex, politically controversial, troop-intensive guerrilla slog in 2005. “In struggles of this type there are seldom suitable targets for massive air strikes,” one military commentator wrote. “Ground forces geared and equipped for large-scale war are notoriously ineffective against guerrillas. Militarily such forces cannot bring their might to bear, and their efforts are all too likely to injure and alienate indigenous populations and thus lose an equally important political battle.”

The stunned Americans—in political and military circles—were ill prepared for this most human of conflicts. This was particularly true of the Army, upon which the greatest burden of the war rested (as usual). Although the service had a long tradition of fighting, and mostly winning, guerrilla wars, the Army had de-emphasized counterinsurgency studies after the painful experience of Vietnam. The Special Operations School at Fort Bragg had even thrown away its counterinsurgency files after Vietnam, an act that was roughly analogous to a group of attending physicians throwing away all case history information on a disease that had just claimed the life of a beloved patient. The Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, along with most every Army development school, offered few if any courses on irregular war. The Army prepared itself to fight conventional wars against similarly structured adversaries. Reflecting the outlook of American policymakers, the Army was preparing for the war it wanted to fight rather than the one it might fight. The 1991 Gulf War only exacerbated the yawning gap in counterinsurgency studies. So, by the Iraq War, the armed forces as a whole were poorly prepared to fight a war against insurgents. “The only way to fill the void was through a career of serious self-guided study in military history,” wrote Colonel Peter Mansoor, a brigade commander with a Ph.D. in military history from Ohio State. “The alternative was to fill body bags while the enemy provided lessons on the battlefield.”

And, tragically, the body bags were being filled, largely because of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Through hard experience, most of the insurgents had learned to shy away from pitched battles with the Americans. Instead they sowed the roads and alleys of Iraq with IEDs. Simple and lethal, an IED was often nothing more than a mortar or artillery shell hidden among roadside debris, dead animals, or dug into a spot alongside or even under the road. Sometimes they were pressure-detonated. More often, a triggerman waited for the Americans to enter a kill zone and then detonated the IED by wire or the electrical signals generated by such mundane items as a cell phone or garage door opener. At times the IEDs were wired up to propane tanks. When the IEDs’ ordnance exploded, the propane ignited, along with the targeted vehicle’s fuel tank, badly burning the victims. IEDs ranged from crude and easily spotted grenades or mortar shells to elaborately prepared traps with daisy-chained artillery shells or hundreds of pounds of explosives capable of destroying a Bradley or even an Abrams tank.

For insurgents, IEDs were perfect standoff weapons, inflicting death on the Americans from a safe distance, impeding their mobility, and eroding their morale and resolve. Insurgents in Iraq used IEDs in much the same way the Viet Cong had used booby traps in Vietnam, but with even greater effect. Whereas 20 percent of American casualties in Vietnam were caused by mines and booby traps, in Iraq IEDs were responsible for more than 50 percent of American deaths by 2006. “They [Americans] are not going to defeat me with technology,” one insurgent told a journalist around this time. “If they want to get rid of me, they have to kill me and everyone like me.” Car bombs and suicide bombers (called VBIEDs and SVBIEDs by American soldiers) only added to the bloody harvest.

All of these frightening weapons were indicative of two undeniable facts. First, there was considerable opposition to the American presence in Iraq. To a distressing extent, insurgent groups reflected the murderous anger and frustration of substantial numbers of Iraqis, or at least their willingness to tolerate such shadow warriors in their midst. Second, they represented the latest illustration of human will in war. They showed that human beings themselves are the ultimate weapons, not machines, no matter how clever, technologically advanced, or useful those machines may be. How, for example, could any machine possibly negate a suicide bomber who was determined to blow himself up because he believes that this was the path to paradise?

Opponents of the American occupation understood that they could not hope to defeat the Americans in a conventional fight, so they adapted, using their own standoff weapons, negating American technological and material advantages. Using the Internet and mass media, they waged information-age political war. Their targets were not just the American soldiers who traversed the roads each day. In a larger sense, they were targeting the will of the American people to continue this faraway war in the face of rising casualty numbers. Day by day, the guerrillas were demonstrating anew one of history’s great lessons, summed up perfectly by Adrian Lewis: “War is ultimately a human endeavor. War is more than killing. And the only thing that technology will ever do is make the act of killing more efficient. Technology alone will never stop a determined enemy. The human brain and the human spirit are the greatest weapons on the Earth.” Indeed they are, and the experiences of one American infantry outfit, circa 2005, illustrate that vital lesson quite well.

1

2-7 Infantry in Saddam’s Backyard

They called themselves the Cottonbalers. Unit lore held that their regimental ancestors had once taken cover behind cotton bales to fight the British during the Battle of New Orleans. In reality, the soldiers of the 7th United States Infantry Regiment probably fought that battle from behind the cover of earthen embankments, but the nickname stuck nonetheless. Proud owners of more battle streamers than any other regiment in the United States Army, the 7th fought in every American war, from 1812 to the twenty-first century. Even a cursory look at their combat history read like an honor roll of U.S. battles—Chapultepec, Gettysburg, Little Bighorn, El Caney, the Marne, Argonne Forest, Sicily, Anzio, Chosin, Tet ’68, Desert Storm, to name but a few. World War II Cottonbalers had fought from North Africa through Italy, France, and Germany all the way to Berchtesgaden, where they captured Hitler’s mountain complex in May 1945 (contrary to popular myth, the

Band of Brothers

paratroopers were not the first into Berchtesgaden).

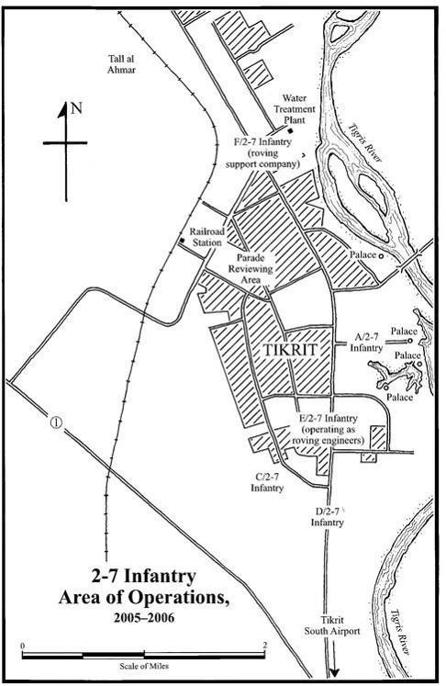

The Cottonbalers of the early twenty-first century were Eleven Mike (11M) mechanized infantrymen. In April 2003, as part of the 3rd Infantry Division, they had led the way into Baghdad. In January 2005, two of the regiment’s battalions, 2-7 Infantry and 3-7 Infantry, returned to Iraq and were assigned responsibility for different sections of the country—Tikrit for 2-7 and western Baghdad for 3-7. Their war this time was radically dissimilar to their April 2003 dash to Baghdad. This time, they were immersed in counterinsurgency.

Located on the Tigris River about eighty miles north of Baghdad, in Salah ad Din province, Tikrit was Saddam Hussein’s hometown and a place dominated by Sunni tribes. This river town of a quarter million people sprouted some of the dictator’s key advisors and many of his elite Republican Guard soldiers. This was especially true of Saddam’s al-Nassiri tribe. In spite of the ties with Saddam’s regime, Tikrit was not a focal point of resistance to the initial American invasion. Only later in 2003 and 2004, partially in response to the occupying 4th Infantry Division’s heavy-handed tactics, did insurgent violence begin to grow. “A budding cooperative environment between the citizens and American forces was quickly snuffed out,” one historian wrote.

By the time the Cottonbalers arrived in 2005, the Americans had begun to reach out to the locals but the insurgency was still going strong. Car bombs, suicide bombings, IEDs, mortar, and rocket attacks were all too common. In Tikrit (and Iraq, for that matter), there was no central resistance group such as the Viet Cong. Instead, there were a dizzying variety of cells, some with only a few members, others numbering in the dozens, with names like Juyash Mohammed, Taykfhrie, Albu Ajeel, and Ad Dwar. Some of the guerrillas were former regime loyalists. Some were Sunni opponents of the Shiite-dominated regime in Baghdad. Some simply resented the American presence in their homeland. Others were part of organized crime groups that had operated in the area for many generations. A comparative few were hard-core al-Qaeda operatives and even some jihadi fugitives from the Fallujah fighting. Most, though, were average people just trying to survive in trying times. “We had a few people that were the hard-core old regime members,” Lieutenant Kory Cramer, a platoon leader in Charlie Company, said. “They were cell leaders. But the majority of the people doing the attacks were normal citizens. They were broke, poor and needed to put food on the table for their families. The cell leaders would pay these guys . . . if they would go out and plant something [IEDs].” The company kept finding mines on one road, only to find out later that a mentally handicapped child was planting them. “His brother or father . . . was telling him to go put these [mines] out there.”

COPYRIGHT © 2010 RICK BRITTON

Just before this deployment, known as Operation Iraqi Freedom III to the soldiers, 2-7 Infantry had been reorganized into a combined arms battalion, a typical process for mechanized infantry battalions by this time. Alpha and Bravo Companies were straight mechanized infantry. Charlie and Delta were armor companies. Easy was engineers and Fox consisted of supporting mechanics, trucks, recovery vehicles, and quartermasters. In practice, out of sheer necessity, most of the soldiers, at one time or another, functioned as dismounted infantrymen, even the tank crewmen and engineers. This was the trend all over Iraq by 2005.

Lieutenant Colonel Todd Wood, a gentlemanly Iowan and former college baseball player with nearly twenty years of experience in the infantry, was the commander. He had about eight hundred soldiers under his charge. They were stretched quite thin in their area of operations because they were responsible for more than just Tikrit. The battalion’s area of operations (AO) also encompassed Bayji, an oil town about forty miles to the north along the river, and most of the desert that led west out of Tikrit, many miles to Lake Tharthar. Lieutenant Colonel Wood spread his companies throughout the AO to cover it as best he could. Alpha Company was in the heart of Tikrit. Bravo Company was in Bayji. Charlie Company covered the outskirt towns of Owja and Wynot, plus the desert where weapons traffickers often operated. Delta had Mukasheifa and another slice of desert. Easy Company operated as roving engineers, infrastructure specialists, and additional infantry. Wood also had, at various times, a light infantry company from the 101st Air Assault Division or a Pennsylvania National Guard mechanized infantry company from the 28th Infantry Division to patrol Kadasia, on the northern outskirts of Tikrit.

2

The soldiers did not live among the people. That approach was an effective counterinsurgency tenet implemented later, during the surge phase of the war. Instead, in 2005, Wood’s troops were housed in forward operating bases (FOBs) with such names as Remagen, Danger, Summerall, and Omaha. They ate and slept in the FOBs and then ventured “outside the wire” to patrol their areas. The typical FOB was located within preexisting buildings, most of which featured the sturdy beige brick structure so common to Iraq. The buildings ranged from old houses to palaces. Each FOB generally consisted of living quarters, a chow hall, a motor pool, a command center, a gym, perhaps even surrounding walls and guard towers. Meals were nutritious and plentiful, offering a variety of foods that grunts of previous wars could only have dreamed about.

Soldiers typically lived in the buildings, or in trailers, two or three to a room. Officers and senior NCOs sometimes had their own rooms. Almost everyone had air-conditioning and, given Iraq’s brutal heat, that was a big deal. “I had a nice room to myself,” Lieutenant Kramer said. “It was about the size of my bedroom back home but I didn’t have to share it with my wife.” Lieutenant Casey Corcoran’s Delta Company was based in a palace called FOB Omaha, though it was anything but lavish. “It didn’t have walls and . . . there were birds and rats living in it with you and the electricity was on and off. But you could say you lived in a palace.”