Gulag (17 page)

Despite the setbacks, the OGPU was fast becoming one of the most important economic actors in the country. In 1934, Dmitlag, the camp that constructed the Moscow–Volga Canal, deployed nearly 200,000 prisoners, more than had been used for the White Sea Canal.

42

Siblag had grown too, boasting 63,000 prisoners in 1934, while Dallag had more than tripled in size in the four years since its founding, containing 50,000 in 1934. Other camps had been founded all across the Soviet Union: Sazlag, in Uzbekistan, where prisoners worked on collective farms; Svirlag, near Leningrad, where prisoners cut trees and prepared wood products for the city; and Karlag, in Kazakhstan, which deployed prisoners as farmers, factory workers, and even fishermen.

43

It was also in 1934 that the OGPU was reorganized and renamed once again, partly to reflect its new status and greater responsibilities. In that year, the secret police officially became the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs—and became popularly known by a new acronym: NKVD. Under its new name, the NKVD now controlled the fate of more than a million prisoners.

44

But the relative calm was not to last. Abruptly, the system was about to turn itself inside out, in a revolution that would destroy masters and slaves alike.

Chapter 6

THE GREAT TERROR AND ITS AFTERMATH

That was a time when only the dead

Could smile, delivered from their struggles,

And the sign, the soul of Leningrad

Dangled outside its prison house;

And the regiments of the condemned,

Herded in the railroad-yards

Shrank from the engine’s whistle-song

Whose burden went, “Away, pariahs!”

The star of death stood over us.

And Russia, guiltless, beloved, writhed

Under the crunch of bloodstained boots,

Under the wheels of Black Marias.

—Anna Akhmatova, “Requiem 1935–1940”

1

OBJECTIVELY SPEAKING, the years 1937 and 1938—remembered as the years of the Great Terror—were not the deadliest in the history of the camps. Nor did they mark the camps’ greatest expanse: the numbers of prisoners were far greater during the following decade, and peaked much later than is usually remembered, in 1952. Although available statistics are incomplete, it is still clear that death rates in the camps were higher both at the height of the rural famine in 1932 and 1933 and at the worst moment of the Second World War, in 1942 and 1943, when the total number of people assigned to forced-labor camps, prisons, and POW camps hovered around four million.

2

As a focus of historical interest, it is also arguable that the importance of 1937 and 1938 has been exaggerated. Even Solzhenitsyn complained that those who decried the abuses of Stalinism “keep getting hung up on those years which are stuck in our throats, ’37 and ’38,” and in one sense he is right.

3

The Great Terror after all, followed two decades of repression. From 1918 on, there had been regular mass arrests and mass deportations, first of opposition politicians at the beginning of the 1920s, then of “saboteurs” at the end of the 1920s, then of kulaks in the early 1930s. All of these episodes of mass arrest were accompanied by regular roundups of those responsible for “social disorder.”

The Great Terror was also followed, in turn, by even more arrests and deportations—of Poles, Ukrainians, and Balts from territories invaded in 1939; of Red Army “traitors” taken captive by the enemy; of ordinary people who found themselves on the wrong side of the front line after the Nazi invasion in 1941. Later, in 1948, there would be re-arrests of former camp inmates, and later still, just before Stalin’s death, mass arrests of Jews. Although the victims of 1937 and 1938 were perhaps better known, and although nothing as spectacular as the public “show trials” of those years was ever repeated, the arrests of the Great Terror are therefore best described not as the zenith of repression, but rather as one of the more unusual waves of repression that washed over the country during Stalin’s reign: it affected more of the elite—Old Bolsheviks, leading members of the army and the Party—encompassed in general a wider variety of people, and resulted in an unusually high number of executions.

In the history of the Gulag, however, 1937 does mark a genuine water-shed. For it was in this year that the Soviet camps temporarily transformed themselves from indifferently managed prisons in which people died by accident, into genuinely deadly camps where prisoners were deliberately worked to death, or actually murdered, in far larger numbers than they had been in the past. Although the transformation was far from consistent, and although the deliberate deadliness of the camps did ease again by 1939— death rates would subsequently rise and fall with the tides of war and ideology up until Stalin’s death in 1953—the Great Terror left its mark on the mentality of camp guards and prisoners alike.

4

Like the rest of the country, the Gulag’s inhabitants would have seen the early warning signs of the terror to come. Following the still mysterious murder of the popular Leningrad Party leader Sergei Kirov in December of 1934, Stalin pushed through a series of decrees giving the NKVD far greater powers to arrest, try, and execute “enemies of the people.” Within weeks, two leading Bolsheviks, Kamenev and Zinoviev—both past opponents of Stalin’s—had already fallen victim to the decrees, and were arrested along with thousands of their supporters and alleged supporters, many from Leningrad. Mass expulsions from the Communist Party followed, although they were not, to start with, much broader than expulsions that had taken place earlier in the decade.

Slowly, the purge became bloodier. Throughout the spring and summer of 1936, Stalin’s interrogators worked on Kamenev and Zinoviev, along with a group of Leon Trotsky’s former admirers, preparing them to “confess” at a large public show trial, which duly took place in August. All were executed afterward, along with many of their relatives. Other trials of leading Bolsheviks, among them the charismatic Nikolai Bukharin, followed in due course. Their families suffered too.

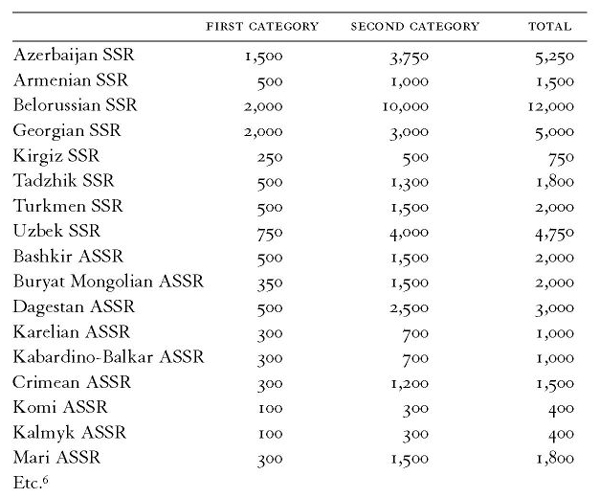

The mania for arrests and executions spread down the Party hierarchy, and throughout society. It was pushed from the top by Stalin, who used it to eliminate his enemies, create a new class of loyal leaders, terrorize the Soviet population—and fill his concentration camps. Starting in 1937, he signed orders which were sent to the regional NKVD bosses, listing quotas of people to be arrested (no cause was given) in particular regions. Some were to be sentenced to the “first category” of punishment—death—and others to be given the “second category”—confinement in concentration camps for a term ranging from eight to ten years. The most “vicious” among the latter were to be placed in special political prisons, presumably in order to keep them from contaminating other camp inmates. Some scholars speculate that the NKVD assigned quotas to different parts of the country according to its perception of which regions had the greatest concentration of “enemies.” On the other hand, there may have been no correlation at all.

5

Reading these orders is very much like reading the orders of a bureaucrat designing the latest version of the Five-Year Plan. Here, for example, is one dated July 30, 1937:

Clearly, the purge was in no sense spontaneous: new camps for new prisoners were even prepared in advance. Nor did the purge encounter much resistance. The NKVD administration in Moscow expected their provincial subordinates to show enthusiasm, and they eagerly complied. “We ask permission to shoot an additional 700 people from the Dashnak bands, and other anti-Soviet elements,” the Armenian NKVD petitioned Moscow in September 1937. Stalin personally signed a similar request, just as he, or Molotov, signed many others: “I raise the number of First Category prisoners in the Krasnoyarsk region to 6,600.” At a Politburo meeting in February 1938, the NKVD of Ukraine was given permission to arrest an additional 30,000 “kulaks and other anti-Soviet elements.”

7

Some of the Soviet public approved of new arrests: the sudden revelation of the existence of enormous numbers of “enemies,” many within the highest reaches of the Party, surely explained why—despite Stalin’s Great Turning Point, despite collectivization, despite the Five-Year Plan—the Soviet Union was still so poor and backward. Most, however, were too terrified and confused by the spectacle of famous revolutionaries confessing and neighbors disappearing in the night to express any opinions about what was happening at all.

In the Gulag, the purge first left its mark on the camp commanders— by eliminating many of them. If, throughout the rest of the country, 1937 was remembered as the year in which the Revolution devoured its children, in the camp system it would be remembered as the year in which the Gulag consumed its founders, beginning at the very top: Genrikh Yagoda, the secret police chief who bore the most responsibility for the expansion of the camp system, was tried and shot in 1938, after pleading for his life in a letter to the Supreme Soviet. “It is hard to die,” wrote the man who had sent so many others to their deaths. “I fall to my knees before the People and the Party, and ask them to pardon me, to save my life.”

8

Yagoda’s replacement, the dwarfish Nikolai Yezhov (he was only five feet tall), immediately began to dispose of Yagoda’s friends and subordinates in the NKVD. He attacked Yagoda’s family too—as he would attack the families of others—arresting his wife, parents, sisters, nephews, and nieces. One of the latter recalled the reaction of her grandmother, Yagoda’s mother, on the day she and the entire family were sent into exile.

“If only Gena [Yagoda] could see what they’re doing to us,” someone quietly said.

Suddenly Grandmother, who never raised her voice, turned towards the empty apartment, and cried loudly, “May he be damned!” She crossed the threshold and the door slammed shut. The sound reverberated in the stairwell like the echo of this maternal curse.

9

Many of the camp bosses and administrators, groomed and promoted by Yagoda, shared his fate. Along with hundreds of thousands of other Soviet citizens, they were accused of vast conspiracies, arrested, and interrogated in complex cases which could involve hundreds of people. One of the most prominent of these cases was organized around Matvei Berman, boss of the Gulag from 1932 to 1937. His years of service to the Party—he had joined in 1917—did him no good. In December 1938, the NKVD accused Berman of having headed a “Right-Trotskyist terrorist and sabotage organization” that had created “privileged conditions” for prisoners in the camps, had deliberately weakened the “military and political preparedness” of the camp guards (hence the large numbers of escapes), and had sabotaged the Gulag’s construction projects (hence their slow progress).

Berman did not fall alone. All across the Soviet Union, Gulag camp commanders and top administrators were found to belong to the same “Right-Trotskyist organization,” and were sentenced in one fell swoop. The records of their cases have a surreal quality: it is as if all of the previous years’ frustrations—the norms not met, the roads badly built, the prisoner-built factories which barely functioned—had come to some kind of insane climax.

Alexander Izrailev, for example, deputy boss of Ukhtpechlag, received a sentence for “hindering the growth of coal-mining.” Alexander Polisonov, a colonel who worked in the Gulag’s division of armed guards, was accused of having created “impossible conditions” for them. Mikhail Goskin, head of the Gulag’s railway-building section, was described as having “created unreal plans” for the Volochaevka–Komsomolets railway line. Isaak Ginzburg, head of the Gulag’s medical division, was held responsible for the high death rates among prisoners, and accused of having created special conditions for other counter-revolutionary prisoners, enabling them to be released early on account of illness. Most of these men were condemned to death, although several had their sentences commuted to prison or camp, and a handful even survived to be rehabilitated in 1955.

10

A striking number of the Gulag’s very earliest administrators met the same fate. Fyodor Eichmanns, former boss of SLON, later head of the OGPU’s Special Department, was shot in 1938. Lazar Kogan, the Gulag’s second boss, was shot in 1939. Berman’s successor as Gulag chief, Izrail Pliner, lasted only a year in the job and was also shot in 1939.

11

It was as if the system needed an explanation for why it worked so badly—as if it needed people to blame. Or perhaps “the system” is a misleading expression: perhaps it was Stalin himself who needed to explain why his beautifully planned slave-labor projects progressed so slowly and with such mixed results.

There were some curious exceptions to the general destruction. For Stalin not only had control over who was arrested, but he also sometimes decided who would

not

be arrested. It is a curious fact that, despite the deaths of nearly all of his former colleagues, Naftaly Frenkel managed to evade the executioner’s bullet. By 1937, he was the boss of BAMlag, the Baikal–Amur railway line, one of the most chaotic and lethal camps in the far east. Yet when forty-eight “Trotskyites” were arrested in BAMlag in 1938, he was somehow not among them.

His absence from the list of arrestees is made stranger by the fact that the camp newspaper did attack him, openly accusing him of sabotage. Nevertheless, his case was mysteriously held up in Moscow. The local BAMlag prosecutor, who was conducting the investigation into Frenkel, found the delay incomprehensible. “I don’t understand why this investigation was placed under ‘special decree,’ or from whom this ‘special decree’ has come,” he wrote to Andrei Vyshinsky, the Soviet Union’s chief prosecutor: “If we don’t arrest Trotskyite-diversionist-spies, then whom should we be arresting?” Stalin, it seems, was still well able to protect his friends.

12