Gulag (49 page)

Curiously, lesbianism in the camps was more open, or at least it is more frequently described. Among the women criminals, it was also heavily ritualized. Lesbians were referred to by the Russian neutral pronoun,

ono

, and they divided themselves into more feminine “mares” and more masculine “husbands.” The former were sometimes “genuine slaves,” according to one account, cleaning and caring for their “husbands.” The latter took on male nicknames, and almost always smoked.

15

They spoke openly about lesbianism, even sang songs about it

O thank you Stalin You’ve made of me a baronness I am both a cow and a bull A woman and a man.

16

They also identified themselves by what they wore, and by their behavior. One Polish woman wrote later that

Pairs of such women are known to everybody, and they make no attempt to conceal their habits. Those who play the part of the man are generally dressed in men’s clothes, their hair is short and they hold their hands in their pockets. When such a pair of lovers are suddenly seized by a wave of passion, they jump up from their seats, leave their sewing machines, and chase after each other, then amid frantic kisses they fall to the ground.

17

Valery Frid writes of criminal women prisoners who, dressed as men, passed themselves off as hermaphrodites. One was “short-haired, pretty, in officer’s trousers”; another did seem to have a genuine genital deformation.

18

Another prisoner described lesbian “rape”: she witnessed one lesbian pair chase a “modest, quiet girl” beneath the bunks, where they broke her hymen.

19

In intellectual circles, lesbianism seems to have been less kindly regarded. One ex–political prisoner remembered it as “a most revolting practice.”

20

Still, although it was usually more hidden among politicals, it did exist among them too, often occurring among women who had husbands and children in freedom. Susanna Pechora told me that in Minlag, a largely political camp, lesbian relationships “helped some people to survive.”

21

Whether voluntary or forced, homosexual or heterosexual, most sexual relationships in the camps shared in the generally brutal atmosphere. Of necessity, they were conducted with an openness that many prisoners found shocking. Couples would “crawl under the barbed wire and make love next to the toilet, on the ground,” one former prisoner told me.

22

“A multiple bunk curtained off with rags from the neighboring women was a classic camp scene,” wrote Solzhenitsyn.

23

Isaak Filshtinsky once awoke in the middle of the night and found a woman lying in the bed next to his. She had snuck over the wall to make love to the camp cook: “Other than myself, no one had slept that night, but with rapt attention listened to the proceedings.”

24

Hava Volovich wrote that “things that a free person might have thought about a hundred times before doing happened here as simply as they would between stray cats.”

25

Another prisoner remembered that love, particularly among the thieves, was “animal-like.”

26

Indeed, sex was so public that it was treated with a certain amount of apathy: rape and prostitution became, for some, part of a daily routine. Edward Buca was once working beside a woman’s brigade in a sawmill. A group of criminal prisoners arrived. They “grabbed the women they wanted and laid them down in the snow, or had them up against a pile of logs. The women seemed used to it and offered no resistance. They had their own brigade-chief, but she didn’t object to these interruptions, in fact, they almost seemed to be just another part of the job.”

27

Lev Razgon also tells the story of a very young, fair-haired girl whom he happened to encounter sweeping the courtyard of a camp medical unit. He was a free worker by then, visiting a doctor acquaintance, and although not hungry, was offered a generous lunch. He gave it to the girl, who “ate quietly and neatly and one could tell that she had been brought up in a family.” She reminded Razgon, in fact, of his own daughter:

The girl finished eating, and neatly piled the plates on the wooden tray. Then she lifted her dress, pulled off her pants and, holding them in her hand, turned her unsmiling face in my direction.

“Lying down or what?” she asked.

At first not understanding, and then scared by my response, she said in self-justification, again without a smile, “People don’t feed me without it . . .”

28

It also happened, in some camps, that certain women’s barracks became little more than open brothels. Solzhenitsyn described one which was incomparably filthy and rundown, and there was an oppressive smell in it, and the bunks were without bedding. There was an official prohibition against men entering it, but this prohibition was ignored and no one enforced it. Not only men went there, but juveniles too, boys from twelve to thirteen, who flocked in to learn . . . Everything took place very naturally, as in nature, in full view, and in several places at once. Obvious old age and obvious ugliness were the only defenses for women there—nothing else.

29

And yet—running directly counter to the tales of brutal sex and vulgarity, there are, in many memoirs, equally improbable tales of camp love, some of which began simply out of women’s desire for self-protection. According to the idiosyncratic rules of camp life, women who adopted a “camp husband” were usually left alone by other men, a system which Herling calls the “peculiar ius primae noctis of the camp.”

30

These were not necessarily “marriages” of equals: respectable women sometimes lived with thieves.

31

Nor, as Ruzhnevits described, were they necessarily freely chosen. Nevertheless, it would not be strictly correct to describe them as prostitution either. Rather, writes Valery Frid, they were “

braki po raschetu

” “calculated marriages”—“which were also sometimes marriages for love.” Even if they had begun for purely practical reasons, prisoners took these relationships seriously. “About his more or less permanent lover, a

zek

would say ‘my wife,’” wrote Frid, “And she would say of him ‘my husband.’ It was not said in jest: camp relationships humanized our lives.”

32

And, strange though it may sound, prisoners who were not too exhausted or emaciated really did look for love. Anatoly Zhigulin’s memoirs include a description of a love affair he managed to conduct with a German woman, a political prisoner, the “happy, good, grey-eyed, golden-haired Marta.” He later learned that she had a baby, whom she named Anatolii. (That was in the autumn of 1951, and, as Stalin’s death was followed by a general amnesty for foreign prisoners, he assumed that “Marta and the child, supposing no bad luck had occurred, returned home.”

33

) The memoirs of the camp doctor Isaac Vogelfanger at times read like a romantic novel, whose hero had to tread carefully between the perils of an affair with the wife of a camp boss, and the joys of real love.

34

So desperately did people deprived of everything long for sentimental relationships that some became deeply involved in Platonic love affairs, conducted by letter. This was particularly the case in the late 1940s, in the special camps for political prisoners, where male and female prisoners were kept strictly apart. In Minlag, one such camp, men and women prisoners sent notes to one another via their colleagues in the camp hospital, which was shared by both sexes. Prisoners also organized a secret “mailbox” in the railway work zone where the women’s brigades labored. Every few days, a woman working on the railroad would pretend to have forgotten a coat, or other object, go to the mailbox, pick up what letters had been sent, and leave letters in return. One of the men would pick them up later.

35

There were other methods too: “At a specific time, a chosen person in one of the zones would throw letters from men to women or women to men. This was the ‘postal service.’”

36

Hunger for Love

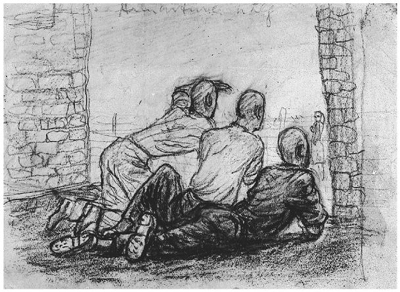

: male prisoners peering over the fence into the women’s zone—a drawing by Yula-Imar Sooster, Karaganda, 1950

Such letters, remembered Leonid Sitko, were written on tiny pieces of paper, with tiny letters. Everyone signed them with false names: his was “Hamlet,” his girlfriend’s was “Marsianka.” They had been “introduced” through other women, who had told him she was extremely depressed, having had her small baby taken away from her after her arrest. He began to write to her, and they even managed to meet once, inside an abandoned mine.

37

Others developed even more surreal methods in their quest for some kind of intimacy. In the Kengir special camp, there were prisoners—almost all politicals, deprived of all contact with their families, their friends, and the wives and husbands they had left back home—who developed elaborate relationships with people they had never met.

38

Some actually married one another across the wall that divided the men’s and women’s camps, without ever meeting in person. The woman stood on one side, the man on the other; vows were said, and a prisoner priest recorded the ceremony on a piece of paper.

This kind of love persisted, even when the camp administration raised the wall, covered it with barbed wire, and forbade prisoners to go near it. In describing these blind marriages even Solzhenitsyn momentarily drops the cynicism he applies to almost all other camp relationships: “In this marriage with an unknown person on the other side of a wall . . . I hear a choir of angels. It is like the unselfish, pure contemplation of heavenly bodies. It is too lofty for this age of self-interested calculation and hopping-up-and-down jazz . . .”

39

If love, sex, rape, and prostitution were a part of camp life, so too, it followed, were pregnancy and childbirth. Along with mines and construction sites, forestry brigades and punishment cells, barracks and cattle trains, there were maternity hospitals and maternity camps in the Gulag too—as well as nurseries for babies and small children.

Not all of the children who found their way into these institutions were born in the camps. Some were “arrested” along with their mothers. Rules governing this practice were always unclear. The operational order of 1937, which mandated the arrests of wives and children of “enemies of the people,” explicitly forbade the arrest of pregnant women and women nursing babies.

40

A 1940 order, on the other hand, said that children could stay with their mothers for a year and a half, “until they cease to need mother’s milk,” at which point they had to be put in orphanages or given to relatives.

41

In practice, both pregnant and nursing women were regularly arrested. Upon carrying out routine examinations of a newly arrived prisoner convoy, one camp doctor discovered a woman having labor contractions. She had been arrested in her seventh month of pregnancy.

42

Another woman, Natalya Zaporozhets, was sent on a transport when she was eight months pregnant: after being knocked around on trains and in the back of trucks, she gave birth to a dead baby.

43

The artist and memoirist Evfrosiniya Kersnovskaya helped deliver a baby who was actually born on a convoy train.

44

Small children were “arrested” along with their parents too. One woman prisoner, arrested in the 1920s, wrote an acid letter of complaint to Dzerzhinsky, thanking him for “arresting” her three-year-old son: prison, she said, was preferable to a children’s home, which she called a “factory for making angels.”

45

Hundreds of thousands of children were effectively arrested, along with their parents, during the two great waves of deportation, the first of the kulaks in the early 1930s, the second of “enemy” ethnic and national groups during and after the Second World War.

For these children, the shock of the new situation would remain with them all of their lives. One Polish prisoner remembered that a woman in her jail cell had been accompanied by her three-year-old son: “The child was well-behaved, but delicate and silent. We amused him as well as we could with stories and fairy tales, but he interrupted us from time to time, saying, ‘We’re in prison, aren’t we?’”

46

Many years later, a child of deported kulaks recalled his ordeal on the cattle trains: “People became wild . . . How many days we traveled, I have no idea. In the wagon, seven people died of hunger. We got to Tomsk and they took us out, several families. They also unloaded several corpses, children, young people, and the elderly.”

47

Despite the hardships, there were also women who deliberately, even cynically, became pregnant while in the camps. These were usually criminal women or those convicted of petty crimes who wanted to be pregnant so as to be excused from hard work, to receive slightly better food, and to benefit, possibly, from the periodic amnesties given to women with small children. Such amnesties—there was one in 1945, for example, and another in 1948—did not usually apply to women sentenced for counter-revolutionary crimes.

48

“You could ease your life by getting pregnant,” Lyudmila Khachatryan told me, as a way of explaining why women happily slept with their jailers.

49