Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (13 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

This effort to re-engineer the politics of Net Neutrality succeeded in another way: FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski lost his will to check the power of these powerful incumbents. He and the agency he led should have tried to clarify the FCC’s authority over broadband and ensure that broadband providers were subject to the same oversight as dial-up ISPs. But after a series of backroom meetings with big telecoms and tech giants, Genachowski deemed the strategy to “reclassify” broadband as a basic transmission service as too politically risky.

(See Alexis Ohanian’s Internet freedom advocacy for a look at the current state of popular Internet activism:

http://www.buzzfeed.com/jwherrman/why-is-this-man-running-for-president-of-the-inter

).

After several failed attempts at compromise, Genachowski’s FCC adopted “Open Internet” rules in December 2010, but it did so using much of the same legal framework that was shot down in the Comcast case. And the rules the FCC adopted are too weak. They offer decent protections for people using wired broadband connections, but almost no protections for the mobile Internet—which will soon be the predominant way most people get online.

Soon after the FCC passed these rules, Verizon announced it was suing; even these industry-friendly regulations were too much for the phone giant. That lawsuit is moving through the same court that ruled in Comcast’s favor last time, and the new case could be decided as early as spring 2013. If the FCC loses—and many fear that it will—then it’s back to the drawing board: there will be no Net Neutrality protections on the books.

The millions of Internet users who became engaged during the Net Neutrality fight spent 2011 getting ready for another big threat to the open Internet to emerge. It didn’t take long.

The first mass protests against the Stop Online Piracy Act and the Protect IP Act took place in November 2011, nearly a year after the FCC passed its Open Internet rules. This time things were a little different.

By late 2006, when the Net Neutrality fight got going, Facebook was just opening up to everyone, Google had just purchased YouTube, and Twitter had just launched. The digital activists that made up the Netroots were few in number, despite the success they were having in framing the political agenda.

By 2011, there were nearly a billion people on Facebook. Tens of millions were using Twitter. Everyday Internet users from around the world had grown accustomed to using the Web to organize protests. President Obama’s 2008 campaign had shown what online activism on a massive scale could look like. The growing numbers of people with Internet access—especially on mobile devices—meant more people could organize and share information.

With SOPA and PIPA, digital activists once again had a clear enemy. The entertainment industry and its friends in Congress were attacking something fundamental to the Web: our culture of online sharing and communication. These bills would hurt Internet users and the online platforms they depend on. With the danger posed to platforms like Google, reddit, Tumblr, and Wikipedia it was only a matter of time before they—along with tens of thousands of startups and individual entrepreneurs—got directly involved in the fight.

SOPA/PIPA was also the second coming of a truly nonpartisan movement for Internet freedom. As in the early days of the Net Neutrality fight, a varied coalition of groups and individuals formed to protect the open Internet. Progressives, libertarians, Tea Partiers, party-line Republicans, startup founders, mom-and-pop business owners, artists, academics, technologists, geeks, and newbies all rallied to the cause … it was as diverse an alliance as one could hope to find, especially in a country as politically polarized as ours.

This confluence of factors—an airtight ethical case, the engagement of millions of everyday Internet users, corporate villains showering cash on Washington lobbyists—echoed previous save-the-Internet campaigns. In many ways, the fight to stop SOPA and PIPA was the heir to the Net Neutrality fight.

1

Roger Crockett, “At SBC, It’s All About ‘Scale and Scope,’”

Businessweek

, Nov. 7, 2005,

http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2005-11-06/online-extra-at-sbc-its-all-about-scale-and-scope

2

The Supreme Court didn’t actually approve on its merits the FCC’s decision to change the regulatory treatment for broadband. The Court simply ruled that, as an “expert agency,” the FCC was entitled to make this decision. Justice Scalia wouldn’t even go that far, however, and in a withering dissent he argued that the FCC had made the wrong decision. He thought it was wrong for the FCC to treat broadband Internet access differently, noting that it provides exactly the same “physical pipe” for delivery of content that telephone lines provide for dial-up ISPs.

http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/04-277.ZD.html

MIKE MASNICK

Mike Masnick is the CEO and founder of Techdirt, a website that focuses on technology news and tech-related issues. Masnick is also the founder and CEO of the company Floor64 and a contributor at Businessweek’s Business Exchange. Techdirt has a consistent Technorati 100 rating and has received “Best of the Web” thought leader awards from Businessweek and

Forbes.

For many, Masnick and Techdirt blew the whistle on COICA—the predecessor to PIPA and SOPA. This entry is adapted from blog posts that he wrote in the fall of 2010

.

In the fall of 2010, two of the entertainment industry’s favorite senators, Patrick Leahy (who keeps proposing stronger copyright laws) and Orin Hatch (who once proposed automatically destroying the computers of anyone caught file sharing … before his own Senate office was found to be using unlicensed software, that is) proposed a new law that would give the Justice Department the power to shut down websites that are declared as being “dedicated to illegal file sharing.”

Perhaps these senators should brush up on their history.

Dare I ask if they realized that Hollywood (who was leaning on them for this law) was established originally as a “pirate” venture to get away from Thomas Edison and his patents? Things change over time. Remember that YouTube, which is now considered by Hollywood to be mostly “legit,” was once derided as a “site dedicated” to “piracy” just a few years ago. It’s no surprise that the Justice Department—with a bunch of former RIAA/MPAA lawyers on staff—would love to have powers to shut down many sites, but it’s difficult to see how such a law would be Constitutional, let alone reasonable. And finally, we must ask: why does the U.S. government consistently seek to get involved in what is, clearly, a civil business model issue? The senators quoted an already well-refuted series of U.S. Chamber of Commerce reports on the supposed “harm” of intellectual property theft—which just shows how intellectually dishonest they were being: they were willing to base a censorship law on debunked data.

Even worse, this proposed law was supposed to have covered sites worldwide, not just in the U. S. For a country that had just passed a libel tourism law to protect Americans from foreign judgments, it’s a bit ridiculous that we were now trying to reach beyond our borders to shut down sites that may be perfectly legal elsewhere. The way that the law, called the “Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act,” would have worked is that the Justice Department could ask a court to declare a site as a “pirate” site and then get an injunction that would force the domain registrar or registry to no longer resolve that domain name—you’d land on an error message or be redirected to a government notice instead.

It’s difficult to consider this anything other than a blatant censorship law. I can’t see how it passed even a simple First Amendment sniff test. It’s really quite sickening to see U.S. senators propose a law that is nothing less than censorship, designed to favor some of their biggest donors in the entertainment industry, who refuse to update their own business models.

There are many serious problems with the way COICA is written, but let’s highlight why it is a bill in service of censorship, and how it opens the door to wider censorship of speech online.

First off, the bill would have allowed the Justice Department to take down an entire website, effectively creating a blacklist, akin to just about every Internet censoring regime operated by the likes of China or those Axis-of-Evil-style foreign states our politicians are prone to shaming and using as evidence of American civil libertarian exceptionalism. Now, it is true that there was sometimes to be a judicial process involved in website blocking under COICA: the original bill had two lists, one that involved the judicial review, and one that did not. The latter was a “watch list” of sites which law enforcement would encourage ISPs and registrars to block, meaning they would block them; you just don’t go out of your way to step on the Attorney General’s big toe.

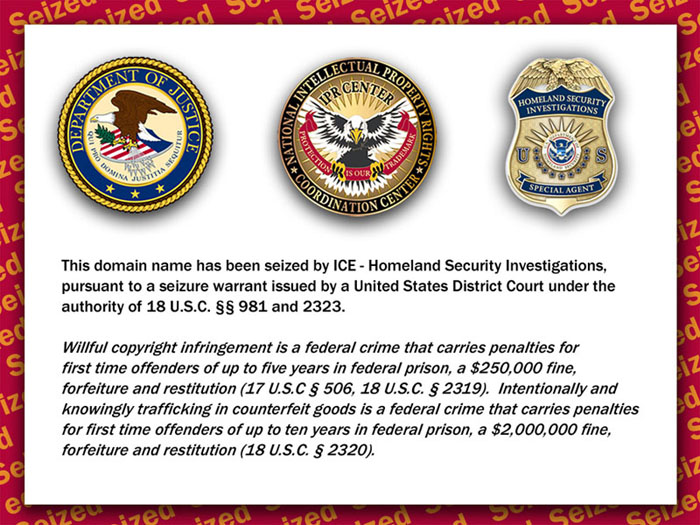

As COICA was being debated, federal law enforcement agencies were starting to use authorities they claim from 2008’s PRO-IP Act to block access to certain domain names and replace their homepages with this image. This provided a stark example of how a broader government-run Internet blacklist might function.

Case law around the First Amendment is clear that you cannot block a much wider variety of speech just because you are trying to stop some specific narrow speech. Because of the respect we have for the First Amendment in the U.S., the law has been pretty clear that anything preventing illegal speech must narrowly target just that kind of speech. Doing otherwise is what’s known as prior restraint.

Two very relevant cases on this front are

Near vs. Minnesota

and

Center for Democracy and Technology vs. Pappert. Near vs. Minnesota

involved striking down a state law that barred “malicious” or “scandalous” newspapers from publishing, allowing the state to get a permanent injunction against the publications of such works. In most cases, what was being published in these newspapers was pure defamation. Defamation, of course, is very much against the law (as is copyright infringement), but the court found that barring the entire publication of a newspaper because of some specific libelous statements barred other types of legitimate speech as well. The court clearly noted that those who were libeled have recourse to libel law to sue the publisher, but that does not allow for the government to completely bar the publication of the newspaper.

The Pappert case—a much more recent case—involved a state law in Pennsylvania that had the state Attorney General put together a blacklist of websites that were believed to host child pornography, which ISPs were required to block access to. Again, child pornography is very much illegal (and, many would argue, much worse than copyright infringement). Yet, once again, here, the courts tossed out the law as undue prior restraint, in that it took down lots of non-illegal content as well as illegal content.

While much of the case focused on the fact that the techniques ISPs were using took down adjacent websites on shared servers, the court did also note

that taking down an entire URL is misguided in that “a URL … only refers to a location where content can be found. A URL does not refer to any specific piece of static content—the content is permanent only until it is changed by the web site’s webmaster … The actual content to which a URL points can (and often does) easily change without the URL changing in any way.” The argument was that taking down a URL, rather than focusing on the specific, illegal content constituted an unfair prior restraint, blocking the potential publication of perfectly legitimate content. The court here noted the similarities to the Near case:

“Additionally, as argued by plaintiffs, the Act allows for an unconstitutional prior restraint because it prevents future content from being displayed at a URL based on the fact that the URL contained illegal content in the past … Plaintiffs compare this burden to the permanent ban on the publication of a newspaper with a certain title,

Near vs. Minnesota

, 283 U.S. 697 (1931), or a permanent injunction against showing films at a movie theater, Vance v. Universal Amusement Co., 445 U.S. 308 (1980). In Near, the Court examined a statute that provided for a permanent injunction against a ‘malicious, scandalous, and defamatory newspaper, magazine, or other periodical.’

“There are some similarities between a newspaper and a web site. Just as the content of a newspaper changes without changing the title of the publication, the content identified by a URL can change without the URL itself changing … In fact, it is possible that the owner or publisher of material on a web site identified by a URL can change without the URL changing. … Moreover, an individual can purchase the rights to a URL and have no way to learn that the URL has been blocked by an ISP in response to an Informal Notice or court order … Despite the fact that the content at a URL can change frequently, the Act does not provide for any review of the material at a URL and, other than a verification that the site was still blocked thirty days after the initial Informal Notice, the OAG did not review the content at any blocked URLs …”