Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (26 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

The initial groundwork of the SOPA fight was hashed out by phone and over email, but to spread the message far and wide we knew we needed to work with policy, academic, and advocacy Internet policy groups and operators of larger websites. First we approached our closest allies, Demand Progress, Public Knowledge, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation. We then reached out to friends we knew at Mozilla, Techdirt, Boing Boing, Hype Machine, Open Congress/Participatory Politics Foundation, and Free Software Foundation, who agreed to sign on.

To get the ball rolling, FFTF worked with Demand Progress and individuals like

Hacking Politics

contributor Elizabeth Stark to organize a brown bag gathering at Mozilla attended by representatives of CDT, EFF, Public Knowledge, Union Square Ventures, Yale and Stanford Universities, Silicon Valley, and others.

These groups joined together on a listserv that became the core venue for anti-SOPA activist organizing over the months to come. Ernesto Falcon at Public Knowledge led legislative strategy on the mailing list and on conference calls. His timely work on the Hill and when he interfaced with grassroots groups was essential. Blogs used videos, infographics, and info sheets to report on the issue.

We began to approach more friends and more people we knew at sites, like reddit, Wikipedia, and Google, who, in turn, knew more people at sites like Scribd and Urban Dictionary. Many Wikipedia users were individually interested in participating in a blackout, and we got the support of the Wikimedia Foundation, but we were told that the decision for Wikipedia to participate in the blackout would require a community-wide conversation and decision-making process. We followed their advice and posted the idea of Wikipedia blacking out on the Village Pump section of Wikipedia, where active users congregate to discuss meta-concerns about the site. We crossed our fingers. Elizabeth Stark reached out to sites like Tumblr and 4chan. Aaron Swartz and David Segal spearheaded outreach to progressive “Netroots” groups like Avaaz, Credo, and MoveOn.

Twitter was chirping about the following day’s protest. In the evening, when 4chan’s founder tweeted that he wished he could support American Censorship Day, we responded immediately and were buoyed by the potential for small ideas to grow. We still did not know if the site itself would participate.

On November 16, huge sites like reddit, Mozilla, Boing Boing and 4chan either linked to our “Write Congress” pages, or included our widget on their

site. In the early morning, we got a call from Tumblr who wanted to make sure we could handle the volume of traffic. We were definitely ready.

Tumblr went above and beyond the call of duty with one of the most creative actions of the protest: they blacked out the dashboards of their over sixty million members, the overwhelming majority of whom had surely never heard of SOPA, or ever engaged in political protest.

Whether or not we’d sunk the bill was still unclear, but the fruits of the campaign were many: it generated over two million petition signers as well as two million emails and eighty-four thousand calls to Congress—four calls per second from Tumblr users alone. Videos and infographics built for the event eventually attracted over six million views and almost three million views, respectively. This was the first major attempt by Internet platforms to mobilize their users en masse. Rep. Zoe Lofgren redacted the logo of her Congressional website. Google, Huffington Post, and AOL placed a full-age ad in the

New York Times

about SOPA. And there was a crack in the armor of the Democratic Party establishment, which had been largely supportive of the bill: responding to the day of protests, Nancy Pelosi tweeted her opposition to SOPA.

American Censorship Day successfully turned SOPA into a viral sensation, but the bills were still, somehow, expected to pass. Our work served to set the stage for an even larger protest to come on January 18. Coming up, there was still the SOPA committee hearing and a final vote on PIPA in the Senate. Ernesto at Public Knowledge made us well aware that we needed further action, and kept the SOPA listserv where activists undertook most of their coordination up to date on the latest legislative events. FFTF and its allies kicked into even higher gear, seeking to expand the number of participating websites.

AARON SWARTZ

There was probably a year or so of delay. And, in retrospect, we used the time to lay the groundwork for what came later. But that’s not what it felt like at the time. At the time, it felt like we were going around telling people we thought these bills were awful and, in return, they thought we were crazy. I mean, kids wandering around waving their arms about how the government is going to censor the Internet? It sounds crazy.

You can ask my friends. I was constantly telling them about what was going on, trying to get them involved, and I’m pretty sure they just thought I was exaggerating. Even I began to doubt myself! I started wondering: was this really that big a deal? Why should I expect anyone to care? It was a tough period.

But when the bill came back and started moving again, it all started coming together. All the folks we had talked to suddenly began really getting involved—and getting others involved. Everything started snowballing.

It happened so fast. I remember one week, I was having dinner with a fellow in the technology industry. He asked what I worked on and I told him about this bill.

“Wow,” he said. “You need to tell people about that.”

I groaned.

And then, just a few weeks later, I was chatting with this cute girl on the subway. She wasn’t involved in the technology industry, but when she heard that I was she turned to me, very seriously, and said “You know, we have to stop SOAP.”

Progress.

But that’s illustrative of what happened during those couple weeks. Because the reason we won wasn’t because I worked to stop SOPA or reddit did or Google or Tumblr or anyone else. It was because there was this enormous mental shift. It was suddenly everyone’s responsibility. Everyone was thinking of ways they could help—often clever, ingenious ways. They made videos and infographics and started PACs and designed ads and bought billboards and wrote news stories and held meetings. Everyone wanted to help.

I remember at one point during this period, I helped organize a meeting of startups in New York, trying to encourage everyone to get involved in doing their part. And I tried a trick that I heard Bill Clinton used to fund his foundation, the Clinton Global Initiative. I turned to every startup founder in the room in turn and said “What are you going to do?”—and they all wanted to one-up each other.

If there was one day that this shift happened, I think it was the day of the hearings on SOPA in the House, the day that we got the phrase “It’s no longer OK to not understand the Internet.” Something about watching those clueless members of Congress debate the bill, watching them insist that they

could regulate the Internet and a bunch of nerds couldn’t stop them—that really brought it home for people. This was happening. Congress was going to break the Internet and it just didn’t care.

It became a popular refrain for SOPA/PIPA protestors to suggest “It’s no longer OK to NOT know how the Internet works.” See the protest signs above from the Jan. 18,2012 NY Tech Meetup.

I remember when that moment first hit me. I was at an event and I got introduced to a U.S. senator—one of the strong proponents of the original COICA bill. And I asked him why, despite being such a progressive, despite giving a speech in favor of civil liberties, he was supporting a bill that would censor the Internet.

And the typical politician’s smile faded from his face and his eyes started burning a fiery red. And he started shouting. Something like, “Those people on the Internet!” He yelled, “They think they can get away with anything! They think they can just put anything up and there’s nothing we can do to stop them! They put up everything! They put up the plans to our fighter jets and they just laugh at us! Well, we’re going to show them. There’s got to be laws on the Internet—it’s got to be under control.”

Now, as far as I know, no one has ever put the plans to U.S. fighter jets up on the Internet. I mean, that’s just not something I’ve heard about. And there’s absolutely no way whatsoever that COICA, PIPA, or SOPA would’ve addressed that issue: it’s simply not what the bills were constructed to do—even a cursory reading of them makes that evident. But that’s sort of the point. It wasn’t a rational consideration—it was an irrational fear that things were out of control. Here was this man, a United States senator! And those people on the Internet? They were just mocking him. They had to be brought under control. Things had to be under control.

That was the attitude of Congress. And just as seeing that fire in the senators’ eyes scared me, I think it scared a lot of people. This wasn’t the attitude of a thoughtful government trying to resolve tradeoffs in order to best represent its citizens. This was the attitude of a tyrant.

And the citizens fought back.

DAVID SEGAL

As a former legislator, I see a committee vote as a key choke point—and typically a point of no return: if a bill makes it through committee it typically means that it has the backing of legislative leadership and that it’s greased and ready to go before the full floor for a final vote, where, for having leadership’s backing, it’s pretty certain to pass. Floor votes are theater. If it fails to make it through committee after an earnest push, it’s likely not going anywhere anytime soon.

To most of the public, a mid-December committee vote is but a form of legislative arcana that’s much less interesting than getting blissful on egg nog. It’s much easier to rally people to take action in front of a floor vote, even though the outcome of such votes is almost always pre-ordained and quite unlikely to be influenced by public pressure.

There was a standing sense that we needed to pull together another meeting of Internet and activist big wigs to try to mobilize more people for the next round of the fight, whenever that might be. I worked hard to convince as many people as possible that it was RIGHT NOW, before the scheduled “markup” of SOPA in the House Judiciary Committee.

A core group of us—Holmes and Tiffiniy at FFTF, Elizabeth Stark, Brad Burnham, and Aaron and I—began to organize in New York. (The Silicon Alley folks, for whatever reasons, got mobilized in opposition to SOPA far faster than the West Coast.)

Brad leaned on his portfolio companies to participate, and with that came a scatter shot of some of the moment’s most influential social media startups, and a home base for the meeting: Tumblr’s hipster-chic offices in lower Manhattan.

We asked Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren to open the call, and she quickly accepted: her gravitas would help draw people in, and she would be able to walk us through the nuts-and-bolts of the markup process. And the techies whom we were hoping would participate would be impressed by her savvy about issues that many of them seemed to assume every last member of Congress was completely ignorant of. (A handful of them actually know a thing or two, and several others are at least aware, and willing to admit, that they don’t know much.)

Millions of people had already joined forces to fight SOPA and PIPA—but that work had overwhelmingly taken part in the virtual space. For me a “meeting” used to mean a face-to-face encounter around a bulky wooded table at the State House or City Hall; now it meant any of dozens of conference calls that took place two or three times a day with people whom I’d never met in real life.

Part of me longed for more real, in-person negotiation and collaboration, and the Tumblr meeting served that purpose and has remained an important marker when I look back on organizing efforts of last fall and winter. Nearly

one hundred people participated, about half of them in person and half on the phones, from throughout the country. Participants ranged from reddit and Tumblr employees to progressive MoveOn organizers to libertarian wonks at Cato, and the meeting provided me with the sense that this was coalescing into a real movement. We were now a team that actually identified as such, with a clear, unified purpose at hand. The mood was upbeat, with a newfound sense that we could win this fight, and the Holiday spirit was in the air: reddit’s Alexis Ohanian showed up in costume, just back from a flashmob of Santas.

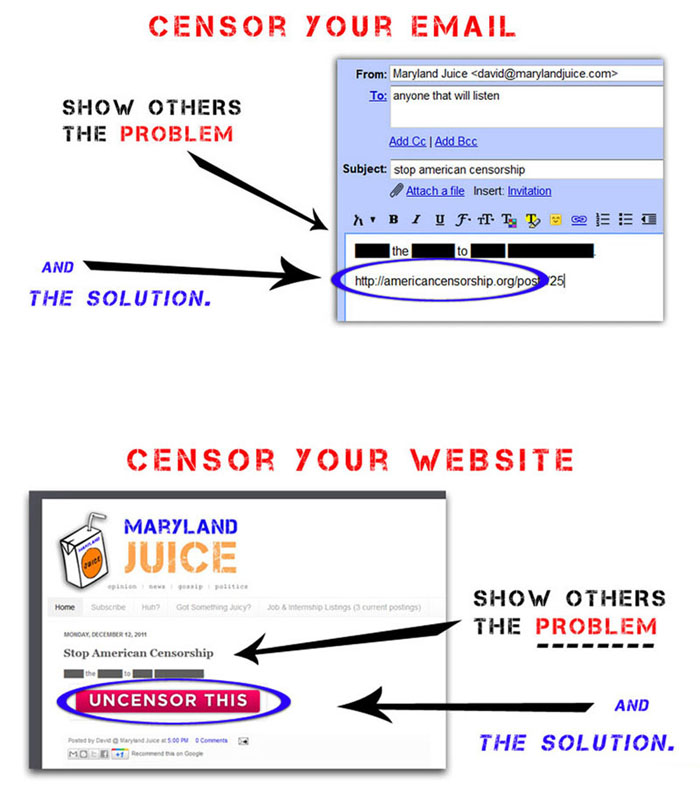

Lofgren implored us to turn up the volume of emails and phone calls—the notion that we should “melt the phones” on Capitol Hill was ubiquitous, but I can’t recall whether or not she uttered that precise phrase. We immediately started brainstorming new sites and tools that we could use to make that happen. Demand Progress and Fight for the Future (who generally had access to a more robust tech team than we did) launched a refresh of several sites and conspired on activism tools, the most novel of which (FFTF’s brainstorm) allowed users to “self-censor” posts to Facebook. Their friends would need to email Congress in opposition to SOPA in order to read the text beneath the redaction.