Read Handbook on Sexual Violence Online

Authors: Jennifer Sandra.,Brown Walklate

Handbook on Sexual Violence (20 page)

Overwhelming force has not been sufficient to have courts put aside their attempts to find some semblance of consent. In

People

v.

Burnham

(1986) a woman was severely beaten and then forced to engage in intercourse with her husband and a dog and the court held out the possibility of consent or at least that the defendant might reasonably believe that she was consenting. So-called ‘submission’, no matter how ‘reluctantly given’, negated the element ‘without consent’ which was an element of the crime of rape. These interpretations of consent eviscerate the normative force of consent. In other words, the reason for requiring consent in the law in the first place is to ensure the moral autonomy of the person is respected. By assuming that women are consenting in all but the most egregious circumstances, the law is not permitting consent to protect women’s sovereignty over their bodies.Race and sexual assault

Many of these rules and standards that made rape prosecution so difficult have lasted well into the present day. The exception to the difficulty of prosecuting rape was in the case of white women charging black men with rape, particularly in the United States, during the period of slavery and the era of systematic legal discrimination and segregation known as the Jim Crow era. In those cases, the law did not require ‘utmost resistance’ since it was assumed that a white woman wouldn’t consent to sexual intercourse with a black man. White women’s testimony was taken as truth and not requiring corroboration. For instance, in Virginia in 1921 a black man was sentenced to the death penalty for a rape of a white, ‘simple, good, unsophisticated country girl’ (

Hartv.

Commonwealth

). The court never looked for her ‘utmost resistance’ nor scrutinised the case. The horrific history of the use of rape charges against black men, many in southern United States resulting in the death penalty, on very little evidence, illustrates another way in which the law has treatedgroups unequally. Black women who were victims of rape did not, however, get similar treatment; in fact their claims of rape, particularly against white men, got very little attention.

Reforming the law

In the 1950s the American Law Institute proposed reforms to the criminal codes of the states including reforms to rape laws. The writers were worried about the extremely low conviction rate for rape. The Model Penal Code, however, keeps the requirements of corroboration of the woman’s testimony, the special cautionary instructions to the jury, the marital exception, and extends the exemption to cases where the man and woman are living together. The Code suggested eliminating the victim’s consent altogether and focusing on the man’s illegitimate behaviour. Changing the focus from the woman to the man’s conduct sounded like a step in the right direction; until then, the woman’s conduct was put on trial, judged, and often found wanting. The status of the victim then becomes a factor in the trial; was she a virgin, was she married, was she a ‘party girl’ or prostitute? Nevertheless, the reasons for not including consent in the Model Penal Code rules rested on sexist notions about women and consent too. The writers assumed that women say ‘no’ and don’t mean it, that women are ambivalent about consent to sex, and that women have conflicting emotions and are unable to directly express their sexual desires. Model Penal Code contributors delineate between forcible rapes, on the one hand, and on the other, reluctant submission. Only the former, forcible rape, was a serious crime. The focus then was on ‘forcible compulsion’ as a trustworthy guide to when women had not consented. But gaining submission without overwhelming violence, through intimidation, threats, deception is recognised as legitimate sexual conduct.

Force continues to this day to play a major part in the understanding of rape. Without physical force, and even extreme physical force, the assumption is that the sexual activity was consensual. As mentioned earlier, Kelly identified a much wider range of sexual violence than what the criminal law recognises as criminal behaviour. The reforms were meant to bring more of the continuum of sexual violence, including non-consensual behaviour without explicit physical force, under the purview of the criminal law. For example, including non-consensual sex without physical force is to expand what the criminal law addresses, so is recognising that ‘rape’ can occur in a marriage. Nevertheless the criminal law has not been very successful in its attempts to secure prosecutions of that wider range of sexual violence.

In the United States, individual states reformed their statutes in the 1960s but didn’t adopt the Model Penal Code’s suggestions wholesale, deciding instead to adopt parts of it, particularly focusing on ‘forcible compulsion’. Most states kept the resistance requirement, the marital exception, the special rules about prompt complaint, corroboration, and the cautionary jury instruction. They reduced the utmost resistance requirement to ‘earnest resistance’ and later ‘reasonable resistance’, keeping to this day the requirement of the woman’s physical resistance (Williams 1963: 162). Current rules and practices

still rely upon a woman’s resistance as necessary evidence that it is a rape. When the victim is intoxicated, or afraid, or for other reasons does not resist, the legal system is unlikely to consider it an instance of rape. The laws continued to see rape as only a violent attack and then only if the woman resists. Non-consensual sex outside of that paradigm was not protected.

Reforms again

In the 1970s feminists such as Susan Brownmiller and Susan Griffin exposed many of the problems with the Anglo-American laws and the criminal justice system’s treatment of rape victims (Griffin 1971). The baseline assumption of consent, the corroboration rule, the routine introduction of a victim’s sexual history, the force and resistance requirement, and the marital exception continued to support the protection of men’s interests in sexual access and not the protection of women’s sexual choice (MacKinnon 1989: 179). Feminists argued that the rules themselves, particularly the force and resistance requirements, embody typical male perceptions, attitudes and reactions rather than female ones. Moreover, some feminists argued that far from protecting women, the rape laws, through their expectations of proper female behaviour and their high expectations of impermissible force, actually served to enhance male opportunities for sexual access. What women wore or did, ‘she wore a tight sweater’, ‘she went to the man’s apartment’, ‘she drank alcohol’, led police and prosecutors to assume that she consented or had only got what she deserved given her dress and behaviour. Feminists argued that the rape laws actually increase a woman’s dependence on a male protector and reinforce social relations of male dominance.

Rape cases that went to trial resulted in the victim being subjected to brutal and humiliating cross-examination of her life, particularly her prior sex life. The object of these cross-examinations was to make her out, no matter how violent or outrageous the alleged rape was, to be a ‘bad girl’ who either consented to the events or got what she deserved given her ‘loose’ lifestyle. Susan Griffin’s article in

Ramparts

magazine in the 1970s was one of the first to document the rape trial ordeal. She described a rape trial where a man, along with three other men, forced a woman at gunpoint to go to his apartment where the four men sexually assaulted her. At trial, other women testified that this man had sexually assaulted them as well. The defence attorney characterised the events as consensual, suggesting that the victim was a ‘loose woman’. The attorney asked her if she had been fired from a job because she’d had sex on the office couch, if she’d had an affair with a married man, and if her ‘two children have a sex game in which one got on top of the other and they . . . ’(Griffin 1971: 971). All of these allegations she vehemently denied; however, the attorney had successfully created in the jurors’ minds a distrust of the victim and a picture of her as a ‘loose woman’. This resulted in the defendant being acquitted. A standard trial tactic was for defence attorneys to ‘put the woman’ on trial, asking questions about her previous sexual experiences, whether she used birth control, whether she went to bars, what she wore, either suggesting that she consented to the sexual events or that she‘got what she deserved’. Recall the 1990s rape trial of Kennedy-Smith (nephew of the late Senator Edward Kennedy), where it was recounted that among other things, the victim’s Victoria’s Secret underwear suggested that anyone who wears such underwear is looking for sex. This played into jurors’ ideas about ‘proper’ female behaviour. Even victims who admitted to having consented to sex with their boyfriends were consequently portrayed as likely to consent to the stranger who was on trial for raping them. In the USA, at the preliminary hearing of the Kobe Bryant rape case, Bryant’s lawyer asked if the victim’s injuries were consistent with her having sexual intercourse with three partners, putting the idea to the media that she had been promiscuous. Bryant, a National Basketball Association superstar, claimed that he had consensual sex with the 19-year-old resort employee. Between Bryant’s scorched earth lawyering and the media’s hounding, the sites all over the Internet about her, and the death threats to her, she eventually withdrew her rape charge.

In the 1970s and the 1980s, response to feminists’ objections resulted in reforms such as dropping the corroboration requirement, the special instruction to juries and eventually presumptive ‘rape shield’ rules to bar defence attorneys from routinely introducing past sexual experiences as a way of undermining the credibility of the victim. How well, for example, the rape shield rules are used is debatable. For instance, Kobe Bryant’s lawyer was able early on to get into play the victim’s sexual history (or even her possible sexual history). And the judges in England, as mentioned earlier, are also subverting the objective of the shield rules.

Concern for equality led some feminists to design gender-neutral statutes, replacing traditional statutes which punished the rape of a woman by a man with gender-neutral ones (Estrich 1987: 81 onwards). Support for gender- neutral statutes also arises from the following concern: ‘Men who are sexually assaulted should have the same protection as female victims, and women who sexually assault men or other women should be as liable for conviction as conventional rapists.’ Gender neutrality is seen as a way ‘to eliminate the traditional attitude that the victim is supposed to resist earnestly to protect virginity, her female ‘‘virtue’’ or her marital fidelity’ (Bienen, 1980: 74–175). Problems, however, arise from making rape statutes gender neutral. Indeed, gender-neutral statutes may address one set of problems but create others. Because women do not necessarily react in the same way as men do, and if gender-neutral statutes mean retaining male norms and reactions to rape scenarios, then women will continue to be disadvantaged by such statutes. So, for example, physical resistance might be a typical male reaction to attack, but not necessarily a typical female reaction. Men are socialised to fight, to respond physically. Women are not and may respond by crying or just being silent.

Subjecting women to the resistance requirement disadvantages them. Further, rape is typically something that is perpetrated on women by men. Rape is not generally a gender-neutral crime; men rape, not women. Women are overwhelmingly the victims of rape. Making rape gender neutral obscures this fact. Gender-neutral statutes are, however, the norm today.

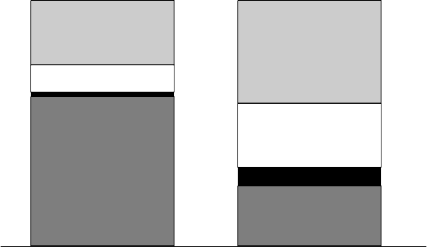

If a man attempted to rape you, do you think you would be most likely to . . .(%)

25

41

11

2

25

61

6

28

Men (2010) Women (2010)

resist

resist submit to avoid injury

submit to avoid injury