Read Handbook on Sexual Violence Online

Authors: Jennifer Sandra.,Brown Walklate

Handbook on Sexual Violence (42 page)

Kocsis

et al

. (2002) looked at 85 Australian sexually motivated murder behaviours, using the same multidimensional scaling procedure as Salfati and Taylor. They found a central core of undifferentiated behaviours that were typical of all sexual murders in the sample and included movement of the body, premeditation and precautions and degree of force used in the sex. Thereafter four subtypes of offence clusters were differentiated which they labelled rape, fury, perversion and predator. These were associated with different degrees of violence and the role of sex in the murders. Moreover they found differences in perpetrators of the different types of murders. The predator pattern was associated with older, mobile offenders, well groomed, living with a partner and highly likely to operate with an accomplice and prone to reoffend. With the fury pattern, where there is an attempt to literally obliterate the victim, offenders are drawn from the violently mentally ill as well as those not suffering from such a disorder. The non-psychotic offender was likened to the anger retaliation rapist whose hatred for women is expressed through violent sexual assault. The taking of souvenirs by this type of perpetrator may act as a reminder of the retributive motivation for the offence.Canter and Ioannou (2004) undertook a multidimensional scaling analysis of stalking behaviours (listed in Table

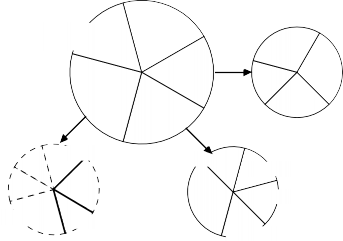

7.2). They had hypothesised that there would be four distinct themes reflecting the mode of interaction with a victim: sexuality, intimacy, aggression-destruction, possession. Thus the differentiation between stalkers they suggested includes sexual infatuation, intimacy seeking, a reactive rejection and passion. This last reflects a belief that the object of the stalking remains the stalker’s ‘property’.If the proposed general model of sexual violence is presented and schematic

representations of the above analyses added, it can be seen that subcrime types do indeed have both overlapping and distinctive themes. In the examples presented in Figure

7.5, stalking and rape have the intimacy theme, reflecting attempts to engage in a relationship albeit in an oppressive way. Interestingly, criminality and possession were distinctive themes in rape and stalking respectively. Within these themes specific behaviours are located that serve similar psychological functions. In stalking the giving of unsolicited gifts mirrors normative affectionate behaviours. The pseudo-intimate rapist attempts to mimic authentic relationships by being solicitous and attempting to engage his victim’s active co-operation in the sex acts he is requiring her to perform. The more violent behaviours in rape and murder go beyond compliance and are often an expression of eroticised sexual aggression.Stalking

Domestic violence

Sexual murder

fury rape

predator

rape murder

sexuality intimacy

Rape

sexuality intimacy

perversion

Kocsis

et al

. (2002)violence impersonal

aggression

possession

Canter and Ioannou (2004)criminality Canter and Heritage (1990)

Figure 7.5

Themes associated with sexual violenceNo equivalent multivariate analyses of domestic violence or sexual harassment have been located but it would be predicted that, if undertaken, then they too would show some common as well as distinctive themes.

Conclusion

This

chapter suggests Kelly’s continuum of violence has been a helpful conceptual tool to build a more complex model having potential explanatory and predictive powers. A general model of sexual violence was presented suggesting a series of continua as radii forming a circular ordering of subclasses of sexual violence. Frequency of behaviours were argued to vary from core or common feature to those that become progressively more differentiating until they identify a specific individual by virtue of the singularity of the actions. Behaviours are linked to themes which can be identified to serve some psychological purpose such as intimacy seeking or venting anger. This model, it is argued, offers a means to differentiate offenders/perpetrators with a view to assessing risk factors in escalation or crossover, designing programmed interventions with offenders, aiding detection, and assessing and treating them.Sexually violent behaviours arise from both normative and pathological routes. Dixon

et al

. (2008) found that they could distinguish different types of sexual murder by looking at levels of psychopathology and criminality. Individuals who were medium to high on criminality and high on psychopathology were more likely to have previously stalked their victim, threatened suicide and engaged in substance misuse. Those high on criminality and low to moderate on psychopathology were more often unemployed, and had had previous convictions for violence. A third groupwho were low on both dimensions had no prior history of violence and more often committed the murder for instrumental gains. This study rather neatly illustrates that sexual violence may be associated with the more normal and mundane motivation of personal gain as well as be a product of psychopathological factors. Bartol and Bartol (2008) note that sex offenders may not be prone to violence or physical cruelty but can be rather timid, shy and socially inhibited. But they also point out that in the United States a class of offender identified as a sexually violent predator was deemed sufficiently dangerous to be subjected to special commitment facilities. Lord (2010) also describes special provisions for offenders classified as having dangerous and severe personality disorders (DSPD). Moreover there is evidence that behaviours associated with different types of sexual violence may indeed escalate and this counters Kelly’s idea that there is not a linear progression in the continuum of violence. Indeed Kelly and her colleague Linda Regan (Regan and Kelly 2008) did propose that previous physical violence, sexual abuse, jealous surveillance, coercive control and an actual or potential separation were factors predicting the eventual murder in domestic violence cases.

The model presented in the chapter argues for a qualitative addition to Kelly’s continuum of violence to chart the relationship between different manifestations of sexual violence such that types of violence having a greater number of behaviours in common are more likely candidates for crossover offending. This is not to say that offenders progress in a linear fashion through the different types of violence, as it may be that a perpetrator only offends within one category; rather there may be different pathways for offenders to progress through different forms of sexual violence. The model suggests a number of hypotheses such as that sexually motivated murderers are likely to be different if they are single-focus offenders compared with offenders who escalate or cross offence boundaries. Some preliminary empirical evidence is offered to support the model, but confirmation awaits further research data.

Further reading

This

chapter draws on a particular approach to research, Facet Theory devised by Louis Guttman. There are accessible accounts of Facet Theory and Facet Design by Jennifer Brown in the

Cambridge Handbook of Forensic Psychology

. In the same text Darragh O’Neil and Sean Hammond provide a description of the statistical procedures described in the chapter, especially Smallest Space Analysis (SSA).David Canter and Donna Youngs’s book

Investigative Psychology; Offender Profiling and the Analysis of Criminal Action

, published by Wiley, provides a good overview and summaries of much of the research drawn on in this

chapter as well as outlining the radex of criminality concept.Salfati and colleagues have two papers that are particularly helpful in explaining the ideas of frequencies of sexually violent behaviour and the notion of a continuum. These are Salfati, G. (2008) ‘Offender profiling; psychological and methodological issues of testing for behavioural consistency’,

Issues in Forensic Psychology

, 8: 68–81 and Salfati, G. and Taylor, P. ‘Differentiating sexual violence; a comparison of sexual homicide and rape’,

Psychology, Crime and Law,

12: 107–25.References

Abdullah-Khan, N. (2008)

Male Rape; the emergence of a social and legal issue

. Basingstoke: Palgrave/Macmillan.Bartol, C.R. and Bartol, A.M. (2008)

Criminal Behaviour; a psychological approach

(9th edn).Upper Saddler River, NJ: Pearson Educational.

Beech, A.R. (2010) ‘Sexual offenders’ in J.M. Brown and E.A. Campbell (eds)

Cambridge Handbook of Forensic Psychology

, pp. 102–10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Bennell, C., Alison, L., Stein, K.

et al

. (2001) ‘Sexual offences against children as the abusive exploitation of conventional adult-child relationships’,

Journal of Social and Personal Relationships

, 18: 115–71.Berdahl, J., and Aquino, K. (2009) ‘Sexual behaviour at work; fun or folly?’,

Journal of Applied Psychology

, 94: 34–47.Bowers, A. and O’Donohue, W. (2010) ‘Sexual harassment’, in J.M. Brown and E.A. Campbell (eds)

Cambridge Handbook of Forensic Psychology

, pp. 718–24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Bradley, F., Smith, M., Long, J. and O’Dowd (2002) ‘Reported frequency of domestic violence; cross sectional survey of women attending general practice’,

British Medical Journal

, 324: 271–5.Breakwell, G. and Rose, D. (2000) ‘Research; theory and method’, in G. Breakwell, S. Hammond and C. Fife-Schaw (eds)

Research Methods in Psychology

(2nd edn), pp. 5–21. London: Sage.

Brown, J.M., Campbell, E.A. and Fife-Schaw, C. (1995) ‘Adverse impacts experienced by police officers following exposure to sex discrimination and sexual harassment’,

Stress Medicine

, 11: 221–8.Brown, J.M., Hamilton, C., and O’Neill, D. (2007) Characteristics associated with rape attrition and the role played by skepticism or legal rationality by investigators and prosecutors.

Psychology, Crime and Law

, 13, 355-370.Campbell, J.C., Webster, D., Kozoil-McLain, J.

et al

. (2003) ‘Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships; results from a multisite case control’,

American Journal of Public Health

, 93: 1089–97.Cann, J., Friendship, C., and Gozna, L. (2007) ‘Assessing crossover in a sample of

sexual offenders with multiple victims’,

Legal and Criminological Psychology

, 12: 149– 63.Canter, D.V. (1994)

Criminal Shadows

. London: Harper Collins.Canter, D.V. (2000) ‘Offender profiling and criminal differentiation’,

Legal and Criminological Psychology

, 5: 23–46.Canter, D. and Fritzon, K. (1998) ‘Differentiating arsonists: a model of firesetting

actions and characteristics’,

Journal of Legal and Criminological Psychology

, 3: 185–212. Canter, D., and Heritage, R. (1990) ‘A multivariate model of sexual offence behaviour:developments in offender profiling’,

Journal of Forensic Psychiatry

, 1(1): 185–212.Canter, D.V. and Ioannou, M. (2004) ‘A multivariate model of stalking behaviour’,

Behaviormetrika

, 31: 113–30.Canter, D.V. and Youngs, D. (2009)

Investigative Psychology; Offender Profiling and the Analysis of Criminal Action

. Chichester: Wiley.DeKeseredy, W. and Kelly, K. (1993) ‘The incidence and prevalence of woman abuse in Canadian university and college dating relationships’,

The Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie

, 18: 137–59.Dixon, L., Hamilton-Giachristsis, C. and Browne, K. (2008) ‘Classifying partner femicide’,

Journal of International Violence

, 23: 74–93.Geberth, V.J. (1992) ‘Stalkers’,

Law and Order

, October: 138–43.Gilchrist, E.A. and Kebbell, M.R. (2010) ‘Intimate partner violence: current issues in

definitions and interventions with perpetrators in the UK’, in J.R. Adler and J.M. Gray (eds)

Forensic Psychology; Concepts, Debates and Practice

, pp 351–77. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.Giner-Sorolla, R. and Russell, P. (2009) ‘Anger, disgust and sexual crime’, in M.A.H. Horvath and J.M. Brown (eds)

Rape; Challenging Contemporary Thinking

, pp. 46–73. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.Groth, A.N., Burgess, A.W. and Holmstrom, L.H. (1977) ‘Rape: power, anger and sexuality’,

American Journal of Psychiatry

, 134, 1239–43.Grubin, D. (1994) ‘Sexual murder’,

British Journal of Psychiatry

, 165: 624–9.Hanson, B.K. and Bussi´ere, M.T. (1998) ‘Predicting relapse: a meta analysis of offender recidivism studies’,

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

, 66: 348–62.