Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (4 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

My father asks her father if he can take his daughter out for the rest of the afternoon. Perhaps a walk on the boardwalk. “

Yes, yes, by all means,

” the bearded face nods in agreement.

My mother and father on the boardwalk at Coney Island

My father and this beautiful girl walk on the boardwalk from Coney Island to Brighton Beach, then back again to the starting point. Although the girl has gone to the Lexington School for the Deaf and is as fluent in sign language as my father, they have said very little to each other. Now they rest on a bench and look at the waves rolling in, one after the other, with great interest, while their hands sit quietly in their laps.

As the light fades from the sky over Coney Island, signaling the beginning of the end of this momentous day, my father takes my mother’s hand in his strong printer’s hands and gently squeezes her fingers. She returns the pressure with a slight acknowledging squeeze of her own.

One week later three strong young men climb five flights of wooden stairs and quickly remove all the splendid two-of-everything rented furniture. Rented by the day, it has served its purpose, now that my father has proposed and Sarah has accepted. On the return trip the men bring up the original shabby, mismatched pieces—which come in ones, not twos.

S

hortly thereafter Louis and Sarah were married. Barely nine months after the wedding, at the height of a thunderstorm, I was born in Coney Island Hospital.

My father’s hands described what that frightful day had been like. His hands appeared to be warding off something. Something unknown that caused fear. “It was a dreadful day,” he signed, throwing out his hands from alongside his temples.

“Awful!”

It was the hottest day of the summer. All of Brooklyn lay stunned beneath the heat. The angry sun had baked the sands of Coney Island and turned the blue Atlantic into a sea of molten red. At dusk the boiling sun continued on its way from Brooklyn to California, taking with it the light but leaving behind the heat.

My father’s hands told me how he paced the grimy linoleum floor of the hospital. From end to end in the airless hallway he measured off his steps: one hundred one way, one hundred back again. And with each step he signed to himself his frustration and his fear.

Back and forth, back and forth, past his wife’s room, past the weeping walls, he walked his endless circle of anxiety. He had been doing this for ten hours, ever since his wife had been admitted after her waters broke so shockingly, signaling the impending birth of their first child.

My father had no thought for the child who was taking his time to arrive, only for his wife, lying on sweat-drenched sheets, in a room he was not permitted to enter, from which few if any news bulletins came his way.

Some time after the sun set a cold front suddenly moved in over Brooklyn, bringing with it a drop of forty degrees in temperature. The cold air rear-ended the darkening boiling mass in its path. Lightning split the sky, and rain fell in cold torrents on to the steaming asphalt streets of Coney Island. Day turned to darkest night.

Soon the tar-topped street outside the hospital was filled from curb to curb with the rising tide of water. The sewers could not handle the overflow, and the water backed up, rising quickly above the hubcaps of the parked cars, flowing down neighboring cellar steps. The violent electric storm spawned winds that toppled trees and tore down telephone poles, while five floors above my father continued his solitary pacing, wondering how he could possibly exist in a world without his deaf wife, Sarah.

Lightning struck oil tanks in New Jersey, sending flames hundreds of feet into the sky, turning night back into blazing day; and the wind tore down a circus tent in Queens, trapping four hundred people beneath the rain-drenched canvas. All the windows of Brooklyn went dark as power lines fell like matchsticks, and my father became a father.

“I rushed out into the storm raising my fist to the heavens,” his hands told me. “I was a crazy man. A Niagara of water submerged me, and all about bolts of lightning splintered the sky.”

Over the crashing sounds of this Olympian tumult, my father’s deaf voice cried out, “

God, make my son hear!

”

C

ould I hear? That was the question. The answer was, he didn’t know.

“But,” his hands continued, “we were determined to find out. And quickly!”

The reason for the doubt on my father’s part was that he and his family had no sure way of knowing the reason for his own deafness. Yes, they all agreed, my father had been quite sick as a young boy; he had run a high fever and, when better, was discovered to have lost all hearing. The same was the case with my mother, who, it was thought, had scarlet fever when just a baby.

But, their parents reasoned, the illness and the deafness were not necessarily connected. Their many other children had also been sick at one time or another, and they had also had high fevers, but they were not deaf. They did not have “broken ears.”

“Both sets of parents were dead set against our having children,” my father signed. “They thought a child of ours would be born deaf. They were ignorant immigrants from the old country.” His hands beat the air angrily. “What the hell did they know? Anyway, they treated us like children. Always. Even when we were adults ourselves. They couldn’t help it. We were deaf, and so we were helpless in their minds. Like children. We would always be children to them. So we did not listen to them, and we had you. They were surprised when they saw how perfect you were. Nothing missing. A regular baby. A

normal

baby in their eyes.

“Mother Sarah and I loved you from the first time we saw you. But secretly some part of us wished you were born deaf.”

Although I loved my father and mother, I could not imagine being part of their deaf world. And I could not understand why even the smallest secret part of them could wish such a fate for me.

“You were our first child,” his hands explained. “We were deaf in a hearing world. There was no one to tell us how to raise a hearing child. We did not have the hearing language to ask. And hearing people did not have our language to tell us. We were on our own. Always. There was no one to help us. How were we to know what you wanted, what you needed? How were we to know when you cried in the dark? When you were hungry? Happy? Sad? When you had a pain in your stomach?

“And how,” he said, “would we tell you we loved you?”

My father paused. His hands were still, thoughtful.

“I was afraid I would not know you if you were a hearing baby. I feared you would not know your deaf father.”

Then he smiled. “Mother Sarah was not worried. She said she was your mother. She would know you. She said you were the son from her body, and you would know your mother. There was no need for mouth-speak. No need for hand-speak.

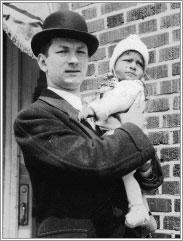

My father and I

“When we brought you home from the hospital, we arranged for Mother Sarah’s family to come to our apartment every Saturday afternoon. ‘

Urgent

!’ I wrote.

‘You must come! Every week. Saturday.’

“They listened. They came from Coney Island every Saturday for all of your first year of life. They never missed, all of them: Mother Sarah’s mother and father, and her younger sister and three younger brothers. They ate like horses, but it was worth it.”

“How boring that must have been for them,” I signed, pressing my finger to my nose as if to a grindstone wheel.

“We didn’t care. I had a plan,” he signed vigorously. “They always came when you were sleeping. I made sure of that. Before making themselves comfortable, I asked them to stand at the back of your crib. Then they pounded on pots and pans I gave them. You heard a big noise and snapped awake, and you began to wail. It was a wonderful sight to see you cry so strongly at the heavy noise sound.”

“Wonderful?” I asked. “Wonderful for who? Now I know why I have trouble sleeping some nights.”

My father continued, ignoring my complaint.

“We celebrated. Mother Sarah served them tea and honey cake. When no one was looking, your Hungarian grandfather, Max the Gypsy, slipped booze into his tea from a silver flask he carried. As he sipped his tea, he would add another shot. Soon his teacup was filled just with whiskey, and he would sip and smile, smile and sip, all afternoon long. ‘Ah, thank God, Myron can hear,’ he would mumble, as he took another sip. Your grandmother, Celia, would look at him in her tight-lipped way, like he was a cockroach she had surprised when turning on the kitchen light late at night. She always looked like she wanted to step on him. No one seemed to notice this, but we deaf see everything. I see more meaning in one blink of an eye than my hearing brother and sisters hear in an hour-long conversation. They understand nothing. The mouth speaks words they hear but teach them nothing. I love my brother and sisters but they are not as smart as me.

“No matter, that’s not part of your hearing story. That’s another story.”

My father’s memories were so intense, and so tightly woven together in his mind, that in the midst of telling one story, he would often wander off into another one that rose to the surface almost as if it had been bottled up all these years and, now that there was someone to tell it to, had just worked itself free. When he did so, he would catch himself and terminate the beginning of the new memory by abruptly signing

another story.

And then I knew that, somewhere down the road, I would hear from him this

other story.

“On Sundays my mother, father, brother, and two sisters came down from the Bronx. They did not trust Mother Sarah’s family. They brought their own pots and pans. Each one held a pot or a pan on their lap during the two-hour, three-subway-ride trip from way up in the Bronx to Kings Highway in Brooklyn. They practiced banging on the pots and pans while the subway cars went careening through the tunnels. The train’s wheels made such a screeching sound that people on the car barely noticed them. When they got off the subway, my sisters and brother marched to our apartment house, still banging the pots and pans. They looked like some ragtag army in a Revolutionary War painting. As soon as they arrived at our apartment, they hid behind the head of your bed and pounded away, while they stomped their feet like a marching band. I felt the loud noise through the soles of my feet. They had a nice rhythm. The result was the same: you awoke immediately. Jumped, actually.”