Hank Reinhardt's Book of Knives: A Practical and Illustrated Guide to Knife Fighting (18 page)

Read Hank Reinhardt's Book of Knives: A Practical and Illustrated Guide to Knife Fighting Online

Authors: Hank Reinhardt

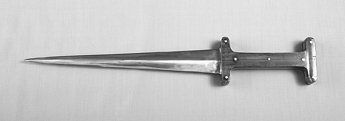

Reproduction medieval baselard, 14¾ inches overall length.

From the collection of Jerry Proctor.

This blade was so popular that it was celebrated in poems, as you can see from the example below. (Okay, not

great

poetry.)

Lesteneth, lordyngs, I zou beseke,

Ther is non man worst (worth) a leke,

Be he sturdy, be he meke,

But he bere a baselard.

Myn baselard hazt a schede of red,

And a clene loket of led,

Me thinketh I may bere up my hed,

For I bere myn baselard.

My baselard hazt a trencher kene,

Fayr as rasour scharp a schene (bright),

Euere me thinketh I may be kene,

For I bere a baselard.

(FROM THE ERA OF HENRY VIII. SLONE MSS)

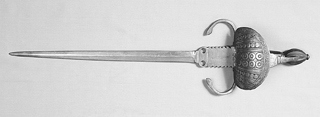

Swords often influence knife shapes. As the rapier became a fighting sword of the late medieval period, the dagger developed into a companion fighting blade in its purest form. With the elaborate hand protection to help facilitate parries, you see development of the elongated guards enhancing the ability to protect the left hand.

Reproduction main gauche, approximately 24–25 inches overall length. “Main gauche” means “left hand” in French.

HRC121

The dagger as a fighting knife has never slowed in its development. An excellent modern example is Randall’s Model No. 2.

Randall No. 2 kit blade, hilted by Hank Reinhardt, 12¾ inches overall length.

HRC603

At the beginning of World War II, knifemaker Bo Randall received a sample of the Fairbairn-Sykes fighting dagger.

A reproduction Fairbairn-Sykes with a metal grip, 11½ inches overall length.

HRC612

As legend has it, Bo threw the knife into a hard local palm tree, and about half an inch of the point snapped off. Bo felt he could do better.

Also it’s quite possible that there was a great deal of input on this project from Colonel Rex Applegate. The truth of the combined effort of these individuals is somewhat lost in the mists of time. Randall’s final product was an extremely strong, well-designed dagger shape which developed a cultlike following. From the lowest-paid GI to the highest ranks of the U.S. military, it is still celebrated today as an excellent example of a dagger.

All fighting knives have advantages and disadvantages. Let your surroundings be your guide. As there is a vast difference between a Ferrari and a tractor, fighting knife shapes vary similarly according to their use. For example, if you are heading into a jungle environment, a kukri is an excellent choice, but not a dagger. Try to pair your weapon with the terrain.

During World War I, a dagger-shaped knife, roughly about five to six inches in length, had been issued to German troops. Later on this same shape with a metal clip-on sheath had been reissued in the Second World War. This was a handy way of concealing your dagger under your clothes or in a boot top.

There are several reproductions of this same dagger still available. It is as good a choice today as it was in 1918. Boker Knives produces this item now. I have stabbed this reproduction into an oak chair top with no bending of the point. Neither the handle scales nor the guard loosened. Right out of the box its blade cut a hundred pieces of half-inch sisal rope without going dull.

I don’t think there is any dagger style more cursed or blessed than the Fairbairn-Sykes Fighting Knife. This double-edged dagger was made famous during World War II through its issue to British Commandos and the nascent SAS. It is still available from many sources today. And used for its intended purpose, as a weapon not a tool, it is a pretty good fighting instrument. I recall back in the day Hank used to talk about going to a surplus store in Atlanta in the 1950s and seeing a barrel full of Fairbairns, different models in various kinds of sheaths, for twenty-five cents each. Boy, have things changed. Now these same knives are selling for $950 to $1,000. Needless to say, this puts them in the high end collection category and out of the cheap carrying category.

You can still get a good Fairbairn reproduction, and they vary greatly in quality. I’ve seen some from Sheffield Cutlery and Flatware of England that were so hard that one could break the point off by merely flexing it. I’ve seen others so soft that they would easily bend by applying a light pressure to the point. Once again, the only way to determine the quality of your knife is to test it.

TESTING THE DAGGER

Put on your safety glasses. Place a paperback book on a table, and put the point of the knife at a 45-degree angle to the book and press down to flex it. Your knife should bend and return to true. Then flip the knife over and repeat the process on the other side. If the knife hasn’t taken a permanent bend, take two paperback books, one on top of the other, and stab into both books, point downward. Here is where you could put that icepick grip to good use. You should have a great deal of penetration. Both the guard and the handle should be intact and not loose.

Once you have tested your dagger, make sure the edges are sharp on both sides. It’s impossible to test a dagger for book-cutting sharpness because of the double edge. However, you can check the edges by seeing if they are shaving sharp. If they are, you are raring to go.

Down through the ages the dagger has been a real whiz-bang in combat and assassinations. Those who consider this knife style as romantic and impractical should consider this story told me by a naval aviator in World War II. His plane was shot down during a sea battle and he quickly found himself floating in a sea full of desperate Japanese soldiers, victims of a nearby troopship sinking. Our hero had on the only life vest available in that part of the Pacific Ocean, and immediately large numbers of Japanese paddled in to take it away from him.

Our aviator stood them off with a .45 automatic until he ran out of ammunition, then he yanked out his dagger boot knife and began stabbing in all directions. He managed this startling stabbing feat because his dagger was secured to his arm by a lanyard. Without it the Japanese could easily have taken the knife away. He continued stabbing and pushing bodies away until he was rescued by a passing destroyer.

If there are any doubters left as to the dagger’s usefulness, consider this story told me by a German soldier, survivor of the frigid Russian front in World War II. As a member of the SS, he had spent a great deal of time on the Eastern Front, where his type was cordially hated by all Russians. My friend and his companion, both tired and cold, were dragging a load of supplies on a sled. They apparently were spending more time looking forward than looking around, because suddenly he was staring down the barrel of a PPsh submachine gun, with two Russian soldiers gazing back at him.

A prisoner on the Eastern Front—not a nice situation under the best of circumstances. My friend cursed himself for his stupidity in not keeping track of his surroundings. Life immediately got much worse than it had before. The Russians piled their own supplies on the sled and made the Germans drag the double load.

The other German soldier had been sick for several days and began coughing and falling down in the snow. The first time he fell, the Russians beat and kicked him to get him back up. He arose and pulled the sled a good distance, then he fell again. This time one of the Russians shot him through the head.

Now my friend knew his goose was really cooked. He struggled to pull the heavy sled, and along the way he began to hatch a scheme. He was wearing three pair of pants, and in the first layer stuck in a pocket was his boot knife. He knew if he fell in the snow the Russians would begin to beat him, at which point he could reach in his pants, pull out his dagger and stab at least one Russian, leaving the odds even. This was a dangerous proposition: they might beat him until he was unable to run, or they might just shoot him. But at this point he would rather be shot than spend the rest of the war in a Russian prisoner of war camp.

He noticed a small stand of trees about a hundred and fifty yards away and this made up his mind. The snow was much harder in that area, making for better footing. So he deliberately slipped and fell down.

When a Russian swinging a Mosin-Nagant rifle came over to beat him, he exploded out of the snow and stabbed the Russian twice in the groin. Then he ran like hell to the shelter of the trees. The other Russian began chasing him and did not stop to take aim—my friend hurled insults over his shoulder to keep the Russian from stopping. He reached the shelter of the trees and the Russian didn’t follow. That thoughtful fellow returned to the sled and mercifully shot his stabbed companion in the head.

There are some important points to be made here: being able to have a concealed dagger can save your life. And being able to thrust into the right target area, very quickly, is the only way to carry it out. He who hesitates is dead meat.

DAGGER TECHNIQUES

Let’s talk about some fighting techniques that are easy with a dagger. This blade shape doesn’t have much cutting power, but it is very quick. It is capable of a fast thrust to your opponent’s forearm or hand. And it cuts in both directions, so a missed cut can be redirected as a reverse slash.