Hard Landing (46 page)

Authors: Thomas Petzinger Jr.

Tags: #Business & Money, #Biography & History, #Company Profiles, #Economics, #Macroeconomics, #Engineering & Transportation, #Transportation, #Aviation, #Company Histories, #Professional & Technical

Charlie Bryan of the machinists’ union at an Eastern shareholders’ meeting in 1986. He told his rank and file, “Weapons formed against you will not prosper!”

(AP/Wide World Photos)

Phil Bakes presided over Eastern’s demise in 1989. “It was as if the people who worked and managed were marionettes.”

(Christopher Morris/Black Star)

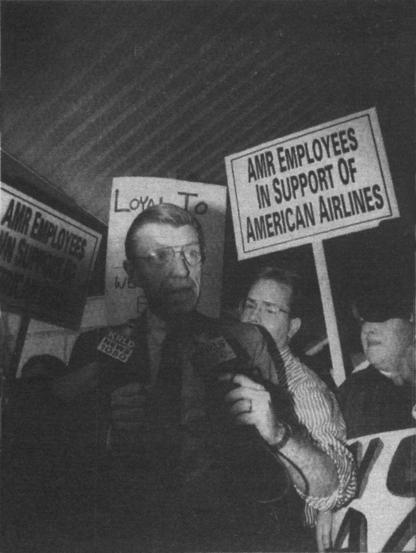

Crandall leads a counterdemonstration as striking flight attendants cripple American in 1993. Management, one official claimed, was victimized by the “gay and lesbian component [in the union membership].”

(AP/Wide World Photos)

Sir Colin Marshall celebrates his 1993 investment in USAir. Asked years earlier to name his dream job, he readily answered. “To be the chairman of British Airways.”

(AP/Wide World Photos)

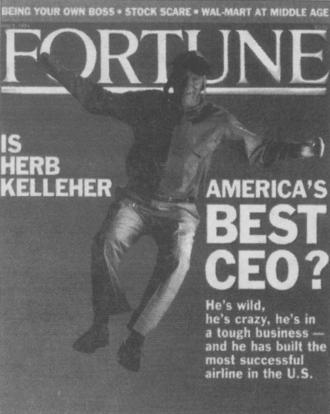

Two decades after its traumatic birth. Southwest hit the East Coast and Herb Kelleher was thrust into the spotlight. “Being a millionaire ain’t what it was in the 1890s,” (F

ORTUNE

is a registered trademark of Time inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.)

CHAPTER 11

GLOOM OVER MIAMI

P

rocessing and transmitting information along an electronic network is an almost wholly derivative activity. Whether a cable television system, a complex of automatic teller machines, or an airline computer reservation system, a network exists not as an end in itself but as a convenience to those who create and consume an underlying product: a Hollywood movie, a banking service, a seat on an airplane. The sociologist Marshall McLuhan’s 1964 assertion that “the medium is the message” is by more recent standards a quaintly over-enthusiastic characterization of the Information Age. Even if the medium is the message, it is not the product. Though it may enhance value, it creates nothing. By themselves computers, networks, and systems can no more fly people between cities than they can print money or direct actors.

Yet in the mid-1980s it almost seemed otherwise to Frank Lorenzo. New York Air and the resurgent Continental Airlines, were, taken together, the largest airline operation in the country without a

direct electronic tie-in to the travel agent community. Some

30,000 travel agencies, accounting for two thirds of all airline reservations, had been hard-wired, but the mainframes of only five airlines resided at the other end. American’s Sabre system remained the leader by far, with 34 percent of the agencies devoted to its system.

United’s Apollo system was still number two, with one quarter of the travel agencies. The remainder of the market was divided among systems operated by Eastern, TWA, and Delta.

When the government moved to crack down beginning in 1983—partly in response to the failure of Braniff and partly in response to the vocal complaints of Frank Lorenzo—Bob Crandall took the lead in defending the systems. “The preferential display of our flights, and the corresponding increase in our market share, is the

competitive raison d’être for having created the system in the first place,” Crandall told Congress. Crandall’s protests were unheeded, however. His system was seen as too successful; he had pushed too far. In late 1984 the government outlawed screen bias.

Lorenzo remained unsatisfied, complaining that American and United still found

ways to play games against him. In January 1985 both systems delayed loading a new round of Continental fare cuts into their systems, making the discounts invisible to travel agencies. (American blamed a power outage; United claimed that Continental had failed to pay the requisite $100 loading fee). Wherever the blame lay, computer reservation systems clearly remained devilishly effective marketing tools. Travel agents could get advance boarding passes on American flights, for instance, only if they were Sabre subscribers. Likewise, only Sabre subscribers could be assured of having the most reliable, last-minute seat availability information.

Even after these and other imbalances were ameliorated by regulation, travel agents sitting in front of terminals leased from American and serviced by American—and that American had trained them to operate—remained significantly more inclined to choose American over other airlines, even when the screen listings were scrupulously neutral. (The same was true of United and its Apollo system.) In study after study the statistics made it clear: a

concentration of terminals in a given geographical area continued to produce a disproportionate amount of business for American (or United, or the other three airlines offering terminals) relative to the number of flights that the airline had in that market. The airlines referred to this phenomenon as the “halo” effect. “

Whether bias exists or not,” Mike Gunn, one of Crandall’s top marketing people, told a sales meeting in 1984, “we know we can get more business from a Sabre-automated account.”

In the minds of Lorenzo and many others the networks were the stuff of economic mythology: guarantees against failure for those who possessed them, assurances of slow death for the have-nots. Frank Lorenzo wanted a halo for himself.

In June of 1985, while the airline industry was transfixed by the bitter strike raging at United, Lorenzo made a deal to acquire Trans World Airlines—his second attempt to take over the first airline he had ever flown, the company whose stock was the first he had ever owned. There was widespread speculation that Lorenzo wanted TWA, with its routes across the Atlantic, to foster a low-fare revolution around the globe. But others knew better. Lorenzo, they could see, had an additional and probably

greater motive: to lay his hands on TWA’s computer reservation system, the same system that Bob Crandall had helped to create in the early 1970s, before joining American Airlines.

In the end, Lorenzo’s reputation would cost him TWA. The company’s unions were so mortified at the idea of having him on the property that they maneuvered the takeover artist Carl Icahn into a position to take control, failing to appreciate that he was no picnic either. There was something vague and off-center about Icahn; whereas Lorenzo was accused of forever backing out of his deals, Icahn would never quite come to closure on one. Lorenzo and Icahn tussled over TWA for weeks, the battle growing increasingly personal. In the end Icahn won TWA. The once-great airline of Howard Hughes became Icahn’s newest cash cow. TWA was as good as dead.

Lorenzo

walked away from the TWA contest with $51 million in trading profits and other payments, a consolation prize of the type he had become so practiced at obtaining. But he was still without a computer reservations network.

For Phil Bakes, watching Lorenzo tangle with Icahn was like watching two

gypsies play cards.

Bakes followed the action, barely, from the distance of the Mediterranean. In the midst of the United strike Bakes had walked away from Continental Airlines for a few weeks for a road trip through his family’s ancestral homelands in Italy. Bakes would later call the trip one of the high points of his life.

He could revel with his family knowing that back home he had

made something of the godforsaken airline that Frank Lorenzo had turned over to him. With the summer schedules of 1985, Continental had not only reached but surpassed the level of operations it had suspended the day it went into Chapter 11 two years earlier. Along the way the company had scored one decisive legal victory after another. The federal judge overseeing the bankruptcy case embraced the company’s move to wipe out its labor agreements, concluding, “There was

no intent or motive to abuse the purpose of the Bankruptcy Code.” (The

judge would soon accept a $250,000-a-year position with one of Continental’s law firms.) Congress, nevertheless, took it upon itself to reform the bankruptcy laws in order to prevent anyone from automatically wiping out wage contracts through bankruptcy, a kind of “Lorenzo Amendment” to the bankruptcy laws.

Bakes also took pride in the company’s marketing triumphs; it was holding its own against United in Denver even without a reservation network. Continental fought back with price, a strategy financed in part by the free use of roughly $1 billion of creditors’ money and labor costs that were only half what they had once been. But nobody could attribute Continental’s success solely to the benefits of bankruptcy. Continental was an on-time airline with good service and a crop of eager and compliant young workers, strikebreakers all.

The traumas had been numerous. The pilots’ union was maintaining its pathetic strike against Continental, as if a strike would reverse the rulings of the bankruptcy court. There had also been public relations setbacks, such as a full-page ad in

USA Today

, signed by Patty Duke, Tony Randall, Daniel J. Travanti, and some 30 other union actors, claiming that Continental cared “more about money than safety.” And there were those pantywaist bankers, forever

imploring Bakes to end the insane fare wars. Bakes would give them a courteous or patronizing brush-off, while thinking to himself, “What are you going to do? Sue us? We’re in Chapter 11!”

Despite all the growth—the furious fleet expansion, the development of the hubs at Denver and Houston—Bakes had kept the lid on costs, in some cases no thanks to Frank Lorenzo. Lorenzo, it appeared to his associates, had an

inferiority complex about abandoning the legacy of superior passenger service for which Continental,

under Bob Six and later Al Feldman, had been so justly famous. Lorenzo was still sensitive about the Mr. Peanut image that stuck to him from the Texas International days. So the same Frank Lorenzo who was getting credit in the business schools as the cost cutter extraordinaire had

jumped all over Bakes when hand-cut radishes and other frills were cut from Continental’s menus.