Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip (29 page)

Read Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #General, #United States, #Automobile Travel, #Biography & Autobiography, #20th Century, #History

It was a wonderful evening. I had been treated like a king—or, better yet, an ex-president. I slept like a baby in Claire’s guest room that night, which is probably how Harry slept the night he stayed with Claire’s parents all those years before.

Harry Truman and Frank McKinney remained close friends for the rest of their lives. And, like Harry, Frank remained active in Democratic Party politics. Over the years he was offered a number of prominent political positions, including a seat on the Securities and Exchange Commission, but he declined them all to stay in Indianapolis. In 1968, at Truman’s urging, President Johnson appointed McKinney ambassador to Spain. It was a challenging assignment. At the time the United States was negotiating with the Franco regime to keep its military bases in Spain. The Senate confirmed McKinney’s appointment, but he was too ill to take the post. He died of cancer in 1974. He was sixty-nine.

St. Louis, Missouri,

July 8, 1953

I

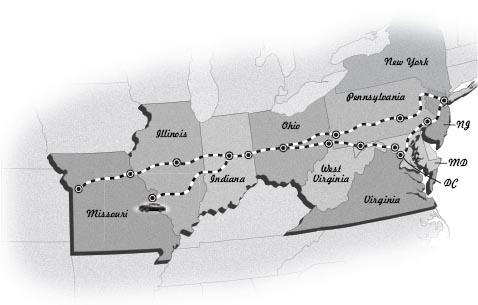

nstead of backtracking along Highway 36 through Decatur and Hannibal, the Trumans took Highway 40 home from Indianapolis. That took them on a more southerly route through Illinois and into St. Louis. Maybe they chose the different route to throw the press off their trail. If so, it worked. Harry and Bess went “missing” again that afternoon. After they left the McKinneys, there were no more reported sightings of the couple until they stopped for dinner in St. Louis at four o’clock, about five hours later.

It was on an earlier trip to St. Louis that the single most enduring image of Harry Truman was captured. On the afternoon of Thursday, November 4, 1948, less than forty-eight hours after his stunning upset in the presidential election, Truman was headed back to Washington on the

Ferdinand Magellan

when the train stopped briefly at Union Station in St. Louis. A crowd of several thousand turned out to greet the triumphant candidate. Among those who met Truman at the station that afternoon was his friend Charles Arthur Anderson, a World War I veteran and former Democratic congressman from Missouri. Somehow Anderson had obtained a copy of the early edition of the previous day’s

Chicago Tribune.

After Truman gave a short speech from the rear platform of the train, Anderson handed him the paper. Beaming, the newly elected president turned toward the crowd and held the paper aloft with both hands for all to see its famously erroneous headline: “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN.” A roar went up. “That’s one for the books,” said Truman laughing. At least three photographers standing shoulder to shoulder directly beneath the president captured the moment: Frank Cancellare of United Press, Pierce Hangge of the

St. Louis Globe-Democrat,

and Byron Rollins of the Associated Press. Their photographs, so identical as to be nearly indistinguishable, would become iconic, a timeless commentary on the fallibility of polls, the virtues of perseverance, and the trustworthiness of the press.

Now, less than five years later, Harry had returned to St. Louis under considerably more modest circumstances. For dinner, he and Bess went to Schneithorst’s, a popular German restaurant at Lambert Field—the St. Louis airport. Yes, once upon a time airports were renowned for their fine dining. Air travel, after all, was glamorous and sophisticated. At the dawn of the jet age, people dressed up to fly, and the airport was a place for the beautiful and the rich, not metal detectors. (The FAA didn’t even require airlines to search passengers and baggage until 1973, after the D. B. Cooper hijacking.) Airports were tourist attractions, too. Thousands came to Lambert Field every month simply to stare in slack-jawed amazement at such modern marvels as the enormous four-engine Douglas DC-6s and Lockheed Constellations.

Schneithorst’s occupied a prized corner of Lambert Field’s terminal, a rectangular two-story brick building that resembled a high school. The restaurant looked out on the runway, so diners could enjoy the spectacle of takeoffs and landings with their Wiener schnitzel à la Holstein and potato pancakes. It was owned by Arthur Schneithorst, who’d held the airport concession since 1940. (As part of the deal, Schneithorst also provided in-flight meals for the airlines based in St. Louis.) He’d seen the restaurant through some lean years during the war, but now business was booming, and Schneithorst’s had become a St. Louis favorite.

How Harry Truman ended up at Schneithorst’s is anybody’s guess. Maybe it was recommended to him when he stopped for gas. Harry tended to regard the recommendations of service station attendants most highly. In any event, as had happened so often on their trip, Harry and Bess weren’t even recognized when they entered the restaurant. But a buzz soon filled the room, and all eyes turned from the runway to the middle-aged couple seated at a table in waitress Virginia Sullins’s section. They ordered veal cutlets.

One bold customer walked up to them to confirm their identities. Harry “admitted the charge,” as he liked to say, and thereafter their meal was constantly interrupted. This had become their usual dining experience. But if they were perturbed, they never showed it. They “laughed and joked with other less famed customers,” the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

reported. They even stayed for dessert, though Mrs. Sullins was by that point so flustered that she had difficulty remembering their order: chocolate ice cream for Harry, more fruit (cantaloupe) for Bess.

The brick terminal at Lambert Field was replaced in 1956 with a striking new building designed by the St. Louis architectural firm of Hellmuth, Yamasaki, and Leinweber. (George Hellmuth would later form HOK, the firm that designed the Abraham Lincoln Museum as well as many ballparks. Minoru Yamasaki went on to design the World Trade Center.) With its vaulted ceilings and glass walls, the terminal suggests a sense of flight. It was one of the firm’s first big projects, and it was an unqualified success. The Lambert Field terminal has been cited as an architectural masterpiece. (Another of the firm’s early projects in St. Louis, the Pruitt-Igoe public housing project, was less well received. It was demolished in 1973.)

Arthur Schneithorst was not awarded the restaurant concession in the new terminal. Undeterred, he built a new, half-million-dollar German restaurant at the intersection of Clayton Road and Lindbergh Boulevard in western St. Louis County. He called it the Hofamberg Inn. St. Louis had never seen anything like it. The sprawling building looked like something straight out of Bavaria, with a clock tower, turrets, and a red-tiled roof. It had three separate dining rooms and two bars, one of which was paneled in walnut and pigskin, with brass figures in bas-relief on the walls. And that was just the first floor. Upstairs were nine banquet rooms. The Hofamberg Inn became a St. Louis institution, but when Arthur’s grandson Jim Schneithorst Jr. took over the business in 2002, the first thing he did was tear the place down. He really didn’t have much choice. The building had become too expensive to maintain, and the demand for schnitzel just wasn’t what it used to be. A “mixed-use development” was built in its place. It includes a very nice restaurant, but, as St. Louisans will tell you, it’s just not the same.

The restaurant concession at Lambert Field is now held by HSMHost, a Maryland-based company that operates restaurants in airports and highway rest stops—sorry, “travel venues”—all over the world. Based on my extensive research, which consisted of asking somebody in the airport’s management office, a restaurant called the Rib Café is roughly where Schneithorst’s used to be. The day I visited happened to be Valentine’s Day, and, by a happy coincidence, Allyson was traveling with me. We planned to return to the airport that night and enjoy a romantic dinner at the Rib Café. Reservations, we assumed, would not be necessary.

If you’ve ever wondered what kind of restaurant would be closed on Valentine’s night, it would be the kind in the St. Louis airport. As Allyson and I discovered when we showed up for dinner at eight, the Rib Café closes at 6:30

P.M.

every day. Even Valentine’s Day. How this fits into HSMHost’s master plan, I don’t know.

Disappointed, we took the shuttle back to our hotel, where we had a completely forgettable dining experience.

The next day we returned to the Rib Café—for lunch. And, as airport restaurants go, it wasn’t half bad. It overlooks the runway, just like Schneithorst’s did, so we could watch planes take off and land while we dined. We ordered ribs, naturally, and they were pretty good. We also enjoyed a tangy coleslaw. The service was efficient. All in all, it was a lovely meal—except for the dead bird on the ledge just outside our window. It lay on its back, in the mid-to late stages of decomposition.

After dinner at Schneithorst’s, Harry and Bess signed a few autographs, then walked out to their car. Harry asked the parking lot attendant for directions back to Highway 40. (Highway 40 and Interstate 64 are now the same road in St. Louis, but the city’s residents—much to their credit— still refer to it as “40,” not “64.”)

Harry and Bess took 40 all the way back to Independence.

They drove straight into the setting sun.

T

he Trumans reached 219 Delaware Street at 9:00

P.M.

on Wednesday, July 8. They’d been gone nineteen days. They’d driven some twenty-five hundred miles. Bess’s brothers George and Frank, who lived around the corner, helped them unpack. “It was a wonderful trip,” Bess told the

Independence Examiner.

Harry skipped his walk the next morning and slept in. He didn’t leave for work until around ten. On the way in, he dropped off his suits at the cleaners. In one of his jacket pockets he discovered the key to his room at the Waldorf. He mailed it back.

Harry and Bess would never take another long car trip. Harry was forced to admit that it was virtually impossible for them to travel incognito anymore. He lamented the loss of anonymity in a letter to his old friend Vic Householder, who had invited Harry to visit him in Arizona. “I’d give most anything to pay a visit to Arizona,” Harry wrote. “But Vic I’m a nuisance to my friends. I can’t seem to get from under that awful glare that shines on the White House…. So, Vic, we’ve decided that until the glamour wears off we’ll only do the official things we have to.”

But as Harry discovered, the glamour of the presidency never wears off. He and Bess did continue to travel, but the trips were choreographed. In 1956 they went to Europe, accompanied by Stanley Woodward, Harry’s former chief of protocol, and Woodward’s wife, Sara. Harry had been to Europe twice before, as an officer in World War I and to confer with Churchill and Stalin at Potsdam, but it was Bess’s first trip overseas. They toured Paris, Rome, and London, meeting with dignitaries including Churchill and Pope Pius XII. On June 20, 1956—exactly three years after he and Bess had driven from Decatur to Wheeling, stopping at the McKinneys’ house for lunch—“Harricum” Truman was awarded an honorary degree at Oxford. “Never, never in my life,” he said, “did I ever think I’d be a Yank at Oxford.” “Give ‘em hell, Harricum!” the students shouted.

Harry, of course, never ran for office again, but he remained active and vocal—some would say too vocal—in the Democratic Party for the rest of his life. He never really stopped being a politician (an honorable profession in his estimation), but he grew less politic. He caused a minor flap in the 1960 presidential campaign when he said anybody who voted for his bitter enemy Richard Nixon “ought to go to hell.” John Kennedy was asked about the comment in one of his famous televised debates with Nixon. “Well,” he said, “I must say that Mr. Truman has his methods of expressing things…. I really don’t think there’s anything I can say to President Truman that’s going to cause him at the age of seventy-six to change his particular speaking manner. Maybe Mrs. Truman can, but I don’t think I can.” (Nixon, whom the Watergate tapes would reveal to be spectacularly profane, responded with his usual sanctimony: “I can only say that I am very proud that President Eisenhower restored dignity and decency and, frankly, good language to the conduct of the presidency of the United States.”)

The first volume of Truman’s memoirs,

Year of Decisions,

was published in 1955. The second,

Years of Trial and Hope,

came out the following year. Sales were strong, but the reviews were tepid. His army of ghostwriters—more than a dozen, by some estimates—had watered down the prose, rendering it a bland imitation of the pugnacious and opinionated president that America had come to know. Harry knew it, too. Across one page of an early draft he scribbled, “Good God, what crap!” (A third book,

Mr. Citizen,

which chronicled his life after the White House, better represented the man.)

In 1955 Harry traded in his 1953 Chrysler New Yorker—for the 1955 model. (If you happen to see the ‘53, please let me know.) It was in the new Chrysler that Harry chauffeured Margaret to Trinity Episcopal Church in Independence on April 21, 1956, for her marriage to Clifton Daniel. It was the same church in which Harry and Bess had been married thirty-seven years earlier. Margaret had met Clifton in New York. He was an editor at the

Times.

“Margie has put one over on me and got herself engaged to a news man!” Harry wrote his old friend Dean Acheson. But, he hastened to add, “He strikes me as a very nice fellow and if Margaret wants him I’ll be satisfied.” Margaret and Clifton would bless Harry and Bess with four grandsons, on whom they doted relentlessly.