Have His Carcase (59 page)

Authors: Dorothy L. Sayers

‘Then the connection won’t go too far back. It’l belong to London or

Huntingdonshire. What

is

Morecambe, by the way?’

‘Described as a Commission Agent, my lord.’

‘Oh, is he? That’s a description that hides a multitude of sins. Wel, go to it,

Superintendent. As for me, I’l have to do something drastic to restore my self-

respect. Seeking the bubble reputation even in the cannon’s mouth.’

‘Oh yeah?’ Harriet grinned impishly. ‘When Lord Peter gets these fits of

quotation he’s usualy on to something.’

‘Sez you,’ retorted Wimsey. ‘I am going, straight away, to make love to

Leila Garland.’

‘Wel, look out for da Soto.’

‘I’l chance da Soto,’ said Wimsey. ‘Bunter!’

‘My lord?’

Bunter emerged from Wimpeys’ bedroom, looking as prim as though he had

never sleuthed in a bad bowler through the purlieus of South London.

‘I wish to appear in my famous impersonation of the perfect Lounge Lizard –

imitation très difficile

.’

‘Very good, my lord. I suggest the fawn-coloured suit we do not care for,

with the autumn-leaf socks and our outsized amber cigarette-holder.’

‘As you wil, Bunter; as you wil. We must stoop to conquer.’

He kissed his hand galantly to the assembly and vanished into his inner

chamber.

XXXII

THE EVIDENCE OF THE FAMILY TREE

‘A hundred years hence, or, it may be, more,

I shall return and take my dukedom back.’

Death’s Jest-Book

Monday, 6 July

The conquest of Leila Garland folowed the usual course. Wimsey pursued her

into a tea-shop, cut her out neatly from the two girl-friends who accompanied

her, fed her, took her to the pictures and caried her off to the Belevue for a

cock-tail.

The young lady showed an almost puritanical discretion in clinging to the

public rooms of that handsome hotel, and drove Wimsey almost to madness by

the refinement of her table-manners. Eventualy, however, he manoeuvred her

into an angle of the lounge behind a palm-tree, where they could not be

overlooked and where they were far enough from the orchestra to hear each

other speak. The orchestra was one of the more infuriating features of the

Belevue, and kept up an incessant drivel of dance-tunes from four in the

afternoon til ten at night. Miss Garland awarded it a moderate approval, but

indicated that it did not quite reach the standard of the orchestra in which Mr da

Soto played a leading part.

Wimsey gently led the conversation to the distressing publicity which Miss

Garland had ben obliged to endure in connection with the death of Alexis. Miss

Garland agreed that it had not been nice at al. Mr da Soto had been very much

upset. A gentleman did not like his girl-friend to have to undergo so much

unpleasant questioning.

Lord Peter Wimsey commended Miss Garland on the discretion she had

shown throughout.

Of course, said Leila, Mr Alexis was a dear boy, and always a perfect

gentleman. And most devoted to her. But hardly a manly man. A girl could not

help preferring manly men, who had

done

something. Girls were like that! Even

though a man might be of very good family and not

obliged

to do anything, he

might stil

do

things, might he not? (Languishing glance at Lord Peter.) That was

the kind of man Miss Garland liked. It was, she thought, much finer to be a

noble-born person who

did

things than a nobly-born person who only

talked

about nobility.

‘But was Alexis nobly born?’ inquired Wimsey.

‘Wel, he

said

he was – but how is a girl to know? I mean, it’s easy to talk,

isn’t it? Paul – that is, Mr Alexis – used to tel wonderful stories about himself,

but it’s

my

belief he was making it al up. He was such a boy for romances and

story-books. But I said to him, “What’s the good of it?” I said. “Here you are,”

I said, “not earning half as much money as some people I could name, and what

good does it do, even if you’re the Tsar of Russia?” I said.’

‘Did he say he was the Tsar of Russia?’

‘Oh, no – he only said that if his great-great-grandmother or somebody had

married somebody he might have been somebody very important, but what I

said was, “What’s the good of saying If,” I said. “And anyhow,” I said,

“they’ve done away with al these royalties now,” I said, “so what are you going

to get out of it anyway?” He made me tired, talking about his great-

grandmother, and in the end he shut up and didn’t say anything more about it. I

suppose he tumbled to it that a girl couldn’t be terribly interested in people’s

great-grandmothers.’

‘Who did he think his great-grandmother was, then?’

‘I’m sure

I

don’t know. He did go on so. He wrote it al down for me one

day, but I said to him, “You make my head ache,” I said, “and besides, from

what you say, none of your people were any better than they should have

been,” I said, “so I don’t see what you’ve got to boast about. It doesn’t sound

very respectable to me,” I said, “and if princesses with plenty of money can’t

keep respectable,” I said, “I don’t see why anybody should put any blame on

girls who have to earn their own living.” That’s what I told him.’

‘Very true indeed,’ said Wimsey. ‘He must have had a bit of a mania about

it.’

‘Loopy,’ said Miss Garland, alowing the garment of refinement to slip aside

for a moment. ‘I mean to say, I think he must have been a little sily about it,

don’t you?’

‘He seems to have given more thought to the thing than it was worth. Wrote

it al down, did he?’

‘Yes, he did. And then, one day he came bothering about it again. Asked me

if I’d stil got the paper he’d written. “I’m sure I don’t know,” I said. “I’m not

so frightfuly interested in it as al that.” I said. “Do you think I keep every bit of

your handwritting?” I said, “like the heroines in story-books?” I said.

“Because,” I said, “let me tel you I don’t,” I said. “Anything that’s

worth

keeping, I’l keep, but not rubbishing bits of paper.” ’

Wimsey remembered that Alexis had offended Leila towards the end of their

connection by a certain lack of generosity.

‘ “If you want things kept,” I said, “why don’t you give them to that old

woman that’s so struck on you?” I said. “If you’re going to marry her,” I said,

“she’s the right person to give things to,” I said, “if you want them kept,” And

he said he particularly didn’t want the paper kept, and I said, “Wel, then, what

are you worrying about?” I said. So he said, if I hadn’t kept it, that was al right,

then, and I said I reely didn’t know if I’d kept it or not, and he said, yes, but he

wanted the paper burnt and I wasn’t to tel anybody about what he’d said –

about his great-grandmother, I mean – and I said. “if you think I’ve nothing

better to talk to my friends about than you and your great-grandmother,” I said,

“you’re mistaken,” I said. Only fancy! Wel, of course, after that, we weren’t

such friends as we had been – at least, I wasn’t, though I wil say he always

was very fond of me. But I couldn’t stand the way he went on. Sily, I cal it.’

‘And

had

you burnt the paper?’

‘Why, I’m sure I don’t know. You’re nearly as bad as he is, going on about

the paper. What does the stupid paper matter, anyhow?’

‘Wel,’ said Wimsey, ‘I’m inquisitive about papers. Stil, if you’ve burnt it,

you’ve burnt it. It’s a pity. If you could have found that paper, it might be

worth–’

The beautiful eyes of Leila directed their beams upon him like a pair of

swiveling head-lamps rounding a corner on a murky night.

‘Yes?’ breathed Leila.

‘It might be worth having a look at,’ replied Wimsey, cooly. ‘Perhaps if you

had a hunt among your odds-and-ends, you know –’

Leila shrugged her shoulders. This sounded troublesome.

‘I can’t see what you want that old bit of paper for.’

‘Nor do I, til I see it. But we might have a shot at looking for it, eh, what?’

He smiled. Leila smiled. She felt she had grasped the idea.

‘What? You and me? Oh,

well!

– but I don’t see that I could exactly take

you round to my place,

could

I? I mean to say –’

‘Oh, that’l be al right,’ said Wimsey, swiftly. ‘You’re surely not afraid of

me

. You see, I’m trying to

do

something, and I want your help.’

‘I’m sure, anything I can do – provided it’s nothing Mr da Soto would

object to. He’s a terribly jealous boy, you know.’

‘I should be just the same in his place. Perhaps he would like to come too

and help hunt for the paper?’

Leila smiled and said she did not think that would be necessary, and the

interview ended, where it was in any case doomed to end, in Leila’s crowded

and untidy apartment.

Drawers, bags, boxes, overflowing with intimate and multifarious litter which

piled itself on the bed, streamed over the chairs and swirled ankle-deep upon

the floor! Left to herself, Leila would have wearied of the search in ten minutes,

but Wimsey, bulying, cajoling, flattering, holding out golden baits, kept her

remorselessly to her task. Mr da Soto, arriving suddenly to find Wimsey

holding an armful of lingerie, while Leila ferreted among a pile of crumpled bils

and picture postcards which had been bundled into the bottom of a trunk,

thought the scene was set for a little genteel blackmail and started to bluster.

Wimsey told him curtly not to be a fool, pushed the lingerie into his reluctant

hands and started to hunt through a pile of magazines and gramophone records.

Curiously enough, it was da Soto who found the paper. Leila’s interest in the

business seemed rather to cool after his arrival – was it possible that she had

had other designs upon Lord Peter, with which Luis’ sulky presence interfered?

– whereas da Soto, suddenly tumbling to the notion that the production of the

paper might turn out to be of value to somebody, gradualy became more and

more interested.

‘I wouldn’t be that surprised, honey-bunch,’ he observed, ‘If you left it in

one of those story-books you’re always reading, same like you always do with

your bus-tickets.’

‘That’s an idea,’ said Wimsey, eagerly.

They turned their attention to a shelf stacked with cheap fiction and penny

novelettes. The volumes yielded quite a surprising colection, not only of bus-

tickets, but also of cinema-ticket counterfoils, bils, chocolate-papers,

envelopes, picture-cards, cigarette-cards and other assorted book-markers,

and at length da Soto, taking

The Girl who gave All

by the spine and

administering a brisk shake, shot out from between its passionate leaves a

folded sheet of writing-paper.

‘What do you say to that?’ he inquired, picking it up quickly. ‘If that isn’t the

felow’s handwriting you can cal me a deaf-and-dumb elephant with four left

feet.’

Leila grabbed the paper from him.

‘Yes, that’s it, al right,’ she observed. ‘A lot of stuff, if you ask me.

I

never

could make head or tail of it, but if it’s any good to you, you’re welcome to it.’

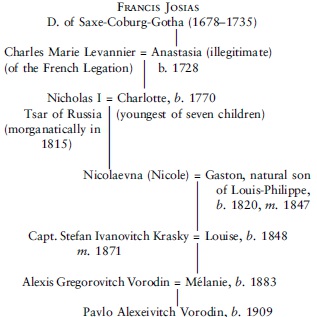

Wimsey cast a rapid glance at the spidery lines of the family tree which

sprawled from top to bottom of the sheet.

‘So that’s who he thought he was. Yes – I’m glad you didn’t chuck this

away, Miss Garland. It may clear things up quite a lot.’

Here Mr da Soto was understood to say something about dolars.

‘Ah, yes,’ said Wimsey. ‘It’s lucky it’s me and not Inspector Umpelty, isn’t

it? Umpelty might run you in for suppressing important evidence.’ He grinned in

da Soto’s baffled face. ‘But I won’t say – seeing that Miss Garland has turned

her place upside-down to oblige me – that she mightn’t get a new frock out of it

if she’s a good girl. Now, listen to me, my child. When did you say Alexis gave

you this?’

‘Oh, ages ago. When him and me were first friends. I can’t remember

exactly. But I know it’s donkey’s years since I read that sily old book.’

‘Donkey’s years being, I take it, rather less than a year ago – unless you

knew Alexis before he came to Wilvercombe.’

‘That’s right. Wait a minute. Look! Here’s a bit of a cinema-ticket stuck in at