Authors: Jennifer Oko

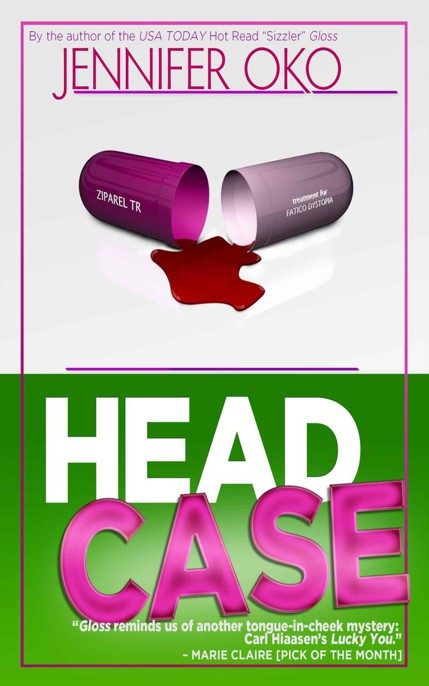

Head Case

HEAD CASE

By

Jennifer Oko

Kindle Direct Publishing Platform

Copyright © Jennifer Oko, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Cover design by Bronson Hoover

This book is dedicated to my friend Jenny Weiner Trewartha, who was there at the beginning of this journey, and to my husband Michael Oko, whose love and support helped me see it through to the end.

For a sizable group of people in their 20’s and 30’s, deciding on their own what drugs to take—in particular, stimulants, antidepressants and other psychiatric medications—is becoming the norm. Confident of their abilities and often skeptical of psychiatrists’ expertise, they choose to rely on their own research and each other’s experience in treating problems like depression, fatigue, anxiety or a lack of concentration … They trade unused prescription drugs, get medications without prescriptions from the Internet and, in some cases, lie to doctors to obtain medications that in their judgment they need.

—The New York Times

Each day in the United States, an army of roughly 100,000 pharmaceutical company sales reps storms the waiting rooms and offices of the nation’s 311,000 office-based physicians. Called “detailers”—and earning, on average, $81,700 per year—they are the smiling, well-dressed men and women often seen in a physicians’ waiting room toting a cavernous briefcase and making small-talk with the receptionists. Their ranks have more than doubled in the last 10 years … In recent years, drug-company insiders have come forward to detail the enticements, persuasive techniques and market-tracking systems that their organizations use to nudge doctors’ prescribing decisions to boost sales.

—The Los Angeles Times

Part One

1

November 5

Right Now.

6:15 P.M.

It’s

all very dramatic. Although I suppose on some level, in the end, that is what Polly wanted. I mean, she didn’t want anyone dead, certainly not anyone she knew. The opposite really. She once told me she just wanted it all to be very alive. Life. Which is drama, right?

I think she was probably right, that to some degree that’s what we all want. Or wanted. If we were going to be satisfied just living our lives with the dull drudgery of the everyday, then why would we spend so much time fantasizing about what’s next, what’s in, what’s hot? If dull drudgery made us fly, Polly wouldn’t even have the silly career she has. Celebrity publicists wouldn’t exist. No one would aspire to anything. And without aspirational living, who would care about celebrities, luxury goods, or, hear me out now, the pursuit of happiness. Right? So maybe there’s a very direct link between our celebrity culture and our societal eagerness to pop a pill.

I know it might sound like a stretch that there could be a connection between designer psychopharmaceuticals and, say, designer fashions, but if you stop to consider that, with the exception of certain celebrity Scientologists, just about everyone who is anyone in the world of the aspirational has certainly popped a few in their time, it makes sense. We live by these assumptions that overnight success is possible, that shiny happy people are models to uphold, that tomorrow any of us could be the next A-lister, the next gazillionaire. Couldn’t there be a connection here? If there is a pill for every little micro-problem in our brains, why not believe that there’s a quick fix for everything else too? I’m sure Polly used to believe that. I know she did.

This is what’s so nice about being dead.

I get to play the role of wise sage, and with an amazing perspective. Because when you die, not only can you flit around the present, you also get to watch stuff in rewind. You get to go inside peoples’ heads in the past tense and follow the firings of their synapses, medicated or not, as they spit them toward the present. Yes, Cher, it turns out that you can turn back time. But the catch is—drum roll please—you can’t be alive to do it. And so, proverbial remote in hand, I’m now able to backtrack; I can take a look and try to figure out how this all happened to my best friend. And by extension, of course, how this happened to me. How, at the ripe age of twenty-eight, with a future as bright as whatever cliché the tabloids will soon be gushing, my body—the body of Olivia Zack—is lying down there in the back of a black Lexus SUV (license plate NYX1KZ, in the event anyone can do anything with this information) while I’m up here, floating around bodiless in the ether, shape-shifting, wall-transgressing, house-haunting, and whatever else it might be that you imagine we ghosts can do. I’m trying to figure that out as well. After all, this is fairly new for me, too. I’ve only been like this for a few minutes, just long enough to zip up to Polly’s apartment and witness her flailing about, waiting for me to come and comfort her once again.

Anyway, in order to figure this out, it seems logical that before I can fully focus on my ending, I need to go back to the source of the whole mess. Because it’s very clear, especially considering the other blood that was spilled near my remains, that I seem to have gotten caught up in a drug war. And I’m not talking crack cocaine. I’m talking Prozac. I’m talking Ritalin. I’m talking Adderall, Lexapro, Zyprexa, Klonopin and what have you. The good stuff. The blockbusters. The billion-dollar babies.

Go get some popcorn. The show’s about to begin.

2

November 5

A Little Bit Earlier (My First Journey Back in Time).

6:00 P.M.

“Fifteen minutes,” I can hear Polly saying to herself. “She said she’d be here in fifteen minutes.”

Which is true. I said that. But given my current and extremely compromised predicament, it’s a little difficult for me to reveal myself to her right now.

I watch as Polly bites her lower lip and eyes the second hand as it jerks past each notch on the wall clock. She picks up her phone and tries calling me again, for the forth time in as many minutes. Of course I don’t answer. But I get the message.

“Olivia,” she says, “what’s going on? You’re twenty minutes late.” She glances back at the clock. “Fine, seventeen.”

She paces the five steps it takes to cross the room and sits on the couch. She stands up. She sits back down. She looks back at the clock. This behavior continues for a few minutes more.

“Olivia, Olivia, Olivia. Where are you?” she says. She pulls herself up and goes to pick up her large periwinkle blue suede purse off the floor of the small foyer, turning the bag over and dumping its contents onto the floor. She collapses to her knees and frantically paws through the pile of pens, matchbooks, lipsticks, crumpled receipts and stale breath mints.

A few random pills, each covered with lint and dust, roll to the side. She picks them up but clearly can’t make out what they are. One is diamond shaped and dark blue. It looks like Viagra. God knows where she picked that up. She throws it hard across the room. It hits the back wall and bounces under the radiator. The others are white, chalky tablets. Probably Advil or Tylenol, or something along those useless lines. She spots a half-eaten roll of her beloved peppermint Certs and grabs it, along with the rest of the junk, and shoves it haphazardly back into the purse.

“Fuck. Fuck, fuck, fuck,” she says out loud. “Get it together, Polly.”

Carefully, slowly, she drags herself to get some water from the pitcher in the fridge. She glances at the mess of photos that cover the door, gym schedules obscuring some, Chinese menus hiding others. Underneath, just one small part of it exposed, there’s a picture of the two of us stuck beneath a magnet (one of those magnetic poetry pieces, this one saying nothing but the word “hither”). The photo is six years old, slightly curled at the ends, and covered with specks of grease from a failed attempt at frying fish. God, it’s been six years already since we stood there, mortarboards flung into the air, giving great shouts of joy and anticipation and relief and uncertainty. We had both lost our mortarboards in the airborne ecstasy, and so in the photograph our long, straightened hair, similarly shaded from the shared bottle of semi-permanent auburn brown we’d purchased the night before, glistens in the sun. From clothing to hair dye, from frivolous gossip to our deepest secrets, we used to share everything. From a few weeks of sharing Polly’s childhood bedroom in her parents’ palatial apartment near Morningside Heights, to sharing our first post-collegiate apartment together over on 92nd Street, which is where Polly is currently pacing, walking from wall to wall. The common space is so small that we had to coordinate inviting anyone over; any more than three people in the apartment and the oxygen will run out.

So, even though things have become a little tense between us of late, even though she hasn’t exactly been straight with me, and even though she says I’ve been too judgmental about her and her life, even if we’ve barely been on speaking terms for the past few months, Polly knows that there’s no one else she could have called at a time like this. And normally, at a time like this, I would have responded.

Polly shuffles herself back over to the couch, trying not to spill her glass of water.

She takes a large gulp, picks up the remote and turns on the TV. It casts a pulsing glow of light around the otherwise dim living room.

“The boardwalk is normally empty this time of year,” a reporter is saying. “But take away the heavy coats and fur hats, and you might think it’s Carnival here in Brighton Beach.”

Polly startles when she hears the words “Brighton Beach.” She watches breathlessly as the reporter continues, peppering in words like “grizzly murder scene” and “shocking” and “local Mafia don Boris Shotkyn was found dead.”

Dead.

Polly spits water all over the cushions.

I know what she’s thinking. She’s thinking about Mitya. He’s the reason she called me, the reason she’s so concerned. But the reporter makes no mention of a tall, dark-haired young man. She does mention, however, that the police are saying that the infamous Boris Shotkyn wasn’t alone. It’s understandable that such information might be upsetting for Polly to hear. Mitya had told her that he was going down there, that he was going to tell Shotkyn once and for all that, if nothing else, they wanted out of the deal. They had lived up to their end of the bargain and gotten him his pills, and fair is fair.

That was this morning.

Shotkyn’s body was found more recently, maybe an hour ago. There was a whole day to account for, and, truth be told, Polly knew perfectly well that if anyone was going to kill Mitya, it probably would have been Shotkyn himself. And it certainly wouldn’t have been a suicide pact.

Ironically, all of our dabbling with antidepressants has become pretty depressing. Well, distressing, anyway.

“Where the hell is she?” Polly says, looking at the ceiling. She sits there, face up, as if some information might fall from the sky. I have to give it to her; it’s a good guess.

She practices mindful inhaling and exhaling.

Slowly, carefully, she takes one last deep, steady breath and looks over toward the front door as if she’s willing it to open. But there’s nothing. Just silence. Then, from the television set, she hears Shotkyn’s name repeated as the announcer teases even more updated, breaking news.

She picks up the remote control again and raises the volume.

“While police say they aren’t ready to release the name of the other victim…”—the reporter is standing on the boardwalk, in front of a hot dog stand, speaking breathlessly—“Oh, hold on a minute, Kate. I’m just getting some new information now. One second. Right. Okay. Kate, we have just been told that yet another body has just been found in the trunk of a car parked near the shipyard. They believe there might be a connection here. Police say this victim is a woman, probably in her mid-to-late twenties. Her identity has not yet been established. We’ll continue following this story and promise to keep you updated as it unfolds. From Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, this is Sarah Schture. Kate?”

“Thank you, Sarah.” The anchor nods and then, attempting a seamless transition to non sequitur, says, “We’ll be back right after this message from our sponsors.”

The screen cuts to a commercial for Ominix, the latest offering from Spitzer Pharmaceuticals, one that promises a cure for acne, incontinence and reflux, all in one pill. Side effects include things like seizures and heart attacks, but the way the gentle-voiced narrator talks about them, they sound like things you might want.

And now it’s five minutes past six and, at least as far as Polly knows, I am nowhere to be found.

3

March 7 (B.D.*)

Eight Months Ago.

4:30 P.M.

*

Before my Death. For the sake of clarity, from this point forth I will refer to dates before my death as B.D. and dates after as A.D. After my Death. Not to be confused with Anno Domini, although they are in fact one and the same.

“Natalie, could you hand me my purse?”

“It’s Polly,” Polly muttered under her breath, leaning forward to pick up the enormous leather bag resting on the floor of the Town Car between Lillianne Farber’s perfectly pedicured feet.

I can picture the scene as if I’d been there myself. Even before my death, before I had these newfound powers of timeless extra-sensorial perception, Polly rehashed the now infamous limo story so many times I might as well have been.

She was escorting Lillianne Farber to yet another interview to promote yet another movie, and was doing her best to maintain a good balance of submissiveness and self-respect, trying her best to live her life and do her job, trying her best not to wrinkle or rip her new pair of $200 designer jeans. (Even though Polly was ambivalent at best about her career, even though her parents—and me for that matter—were constantly pushing her to find a real career, and even though she agreed that her particular job was not entirely fulfilling, she still worked hard to keep up appearances. She believed it was a professional requirement. Somehow, on a yearly salary that your average CEO makes in the time it takes him to piss, young publicists like Polly were supposed to dress like the trend-setting social elites they represented, no matter how much said elites treated them like peasants.)

She’d been with Lillianne for three days now, Lillianne’s guide for a whirlwind media tour of New York (Lillianne hated doing this stuff, and preferred to jam pack her schedule to get her contractual obligations over and done with), and even though Polly looked like a stylish and respectable person, she could count on one hand the number of times Lillianne had called her by her actual name. She wouldn’t even need all her fingers. But Polly couldn’t decide if this was her fault or Lillianne’s. She figured that to be a person like Lillianne required such a deep level of self-importance that you almost couldn’t hold it against her. It was one of Lillianne’s professional requirements. But she must know some peoples’ names, and Polly supposed it would be nice to be one of those people whose name people like Lillianne actually remembered.

“Um,” Polly said softly, tugging gently at the buttery soft leather strap. “Your heel?”

Lillianne’s stiletto was pinning down the purse, but she glared at Polly as if it was her fault she couldn’t pick the bag off the floor.

“Jesus Christ, Natalie,” Lillianne said, jerking her leg up like she had just been stung by a bee.

Polly heaved up the bag and placed it on the seat between them. Without looking at Polly or thanking her, Lillianne pulled it into her own lap and started burrowing through it.

“Shit,” she said. “Shit, shit, shit.”

“Is everything okay?” Polly asked with a preemptive sense of guilt churning up in her gut; she sensed she would be blamed for whatever it was Lillianne was upset about.

“Obviously not,” said Lillianne. She riffled around for another minute and then threw the bag back on the floor, causing some of the contents to spill out (a lip gloss, some pens, her cell phone, which Polly tentatively picked up and put back in the bag). “My fucking drugs. I left them in LA.”

Polly wasn’t sure what to say, or if Lillianne expected her to say anything, so she just bit her lower lip and gently nodded her head.

“So?” Lillianne looked expectantly at Polly.

“Uh?”

“Natalie, what are we going to do about this?”

As Polly freely admitted herself (and admitted often), she had done a lot of idiotic things for her clients over the years. I could never comprehend why she repeatedly, knowingly debased herself like this, but as much as she complained about it, she always insisted such behavior was necessary and somehow acceptable. She groveled with department stores to open up after hours. She sheepishly picked up unpaid bar tabs and left over-sized tips for oppressed wait staff with camera phones. She wrote fraudulent notes of apology, sent flowers, cleaned carpets, broke up with lovers, lied to journalists, you name it. But drugs? She hadn’t gone there. She didn’t do drugs, not for her clients and not for herself. I mean, sure, she had inhaled a few times in college, but that was about it. It just wasn’t her thing. She’d rather a good martini any day, even if it was more caloric.

Lillianne sighed with Oscar-worthy exaggeration. “I don’t have time for this shit. How am I supposed to get a prescription filled right now? Damn it.”

Oh. That kind of drug. A prescription drug. “Are you sick?” Polly asked, perking up at the chance to somehow be helpful. She did that. The ruder someone was to her, the more she wanted to placate them. It drove me crazy, but I guess it was what made her good at her job. I’m not like that. Or I wasn’t. If someone was bitchy to me, I usually just turned my back.

Lillianne rolled her eyes. “No, silly. I’m not sick. It’s for Sentofel. I just need it to keep focused while doing this crap.”

Oh. Those kinds of prescription drugs. Polly had some in her own bathroom. We all did. We all do. Well, most of us do. Polly had been popping them since she was seventeen. It started with Prozac. Well, it wasn’t actually Prozac. Not at first. By the time Polly went on the medication, the generic version was available, so instead of the $50 co-pay, her folks only had to cough up $10 a month. Which really wasn’t much, considering. But later, after college, when her dependent status insurance ran out, those $10 became $150, even for the generic. She would have just gone off it except that her dad, a psychiatrist himself, was able to provide her with some free samples. He had a large supply; well-groomed pharmaceutical reps were constantly parading through his clinic. The sample-filled gift bags and boxes they gave to doctors came complete with branded coffee cups, mouse pads, and even, upon occasion, Prozac-shaped and colored cookies as holiday treats. The cookies were oval, like a pill, with green and cream-colored icing. Kind of like those half-black half-white sugary affairs, but this time with food dye and no chocolate. When Polly first told me about all of this, I said that I thought it made some logical sense that they didn’t distribute chocolate cookies because, as I knew from my own research, chocolate has antidepressant properties and pharmaceutical companies were already having enough trouble from the generics and the competition as it was.

Polly told me she ate them anyway.

She said she brought them to parties, where everyone got a big kick out of the confections. The cookies were even funnier, more ironic, than the silver rings and pendants that were in vogue back then, the ones that had names of medications stamped on them so that everyone could announce their drug of choice with proud detachment. RITALIN circling the ring finger, ZOLOFT worn almost aggressively on the thumb. The dean of her school actually banned what he called “sardonic (he had to get the SAT word in there) accessories” after a point, because, he said, they were fostering a disturbing sense of self among the student body. Polly just thought they were clunky and unattractive.

It wasn’t that she was all that depressed. Not at the beginning. It was more like she was not not depressed. Or something like that. But tell that to the parents of any teenager, not to mention parents who are themselves particularly sensitive to the mental health issues surrounding the later stages of adolescence, and it wasn’t so much a hard sell as a cry, well really a whimper, for help. Polly recognized that now. But the real reason, or at least what she told herself then, that she had asked her parents to get her the prescription, or at least the referral to a doctor who would, since it wasn’t ethical for her dad to write it himself (and if anything, her father was ethical), was as simple as the main reason that teenagers have been doing things for millennia—everyone else was doing it.

After realizing one night during her junior year of high school, at a party at Seth Walden’s house, when everyone put one of their own pills—the sedatives, the stimulants, the antidepressants—in the candy bowl (these weren’t street drugs after all, so what was the harm?) and then, blindfolded, pulled another one out and popped it, that she was in the small minority of students at her school who wasn’t on something, Polly decided it was time to brand herself along with the rest of them, claim an identity. Funny how things can come full circle like that, because if you ask me, those drugs are a big part of her identity now.

Anyway, Polly said that what was weird was that when she started to take the drugs back then, she really did feel better. Eventually. More confident, less indecisive, less like an insecure teenager and more like an adult. Or at least what she thought an adult should feel like. Which was in fact one of the diagnostic criteria for the drug; if it worked, it meant it had something to work on, so by deduction, that meant that she, Polly Warner, like tens of millions of other Americans, suffered from depression, and therefore needed to do something about it. She’d been doing something about it for more then ten years by the time she was riding in that car with Lillianne Farber.

Lillianne was looking out the window, sighing repeatedly, acting like she was on the verge of a major crisis. Maybe she was. But Sentofel wasn’t exactly a big deal drug. I mean, it wasn’t addictive or anything and it was about as common as Tootsie Rolls. I swear it was the only way half of us passed our college finals. I’m sure it was how Lillianne passed hers. She was one of those Hollywood starlets touted as being smart because she graduated from an Ivy League college. It was like this huge deal that not only was she beautiful, she could also calculate hundreds of digits of Pi. Or something. Although I can’t imagine that having a filmography like hers hurt her college application process. Seriously, what college would turn away a hot young actress who, at the tender age of ten, had already been nominated for not one but two Oscars? Not that she won. But still. And then there was all of her humanitarian causes, all of those photos of her in People and Us playing with AIDS orphans in Africa and helping to distribute food in Sudan. When she was thirteen. It sure put Polly’s sophomore year stint as a candy striper at her father’s hospital in perspective.

“So?” Lillianne said, still looking at the passing buildings and street signs and pedestrians and God knows what, rather than at Polly.

So?

Polly didn’t respond because she wasn’t sure what Lillianne expected her to say. She was still thinking through her plan. She had already ruled out calling her father; he was so ethical that it wouldn’t prove any less cumbersome than calling Lillianne’s doctor. And even if he would agree to call in a prescription, they’d still have to go to the pharmacy. They’d still have to wait at least another half hour to get it filled.

Lillianne, meanwhile, was losing what little patience she had. “Nancy, you can’t really expect me to go on the next round of interviews like this, can you? It isn’t going to look very good for me or for the film if I can’t focus. And that isn’t going to look very good for you, now is it?”

“Um … it’s Polly …”

“So I suggest you figure this out.”

Which was how Lillianne Farber—gazillionaire Hollywood starlet, woman all men want to be with and all women want to be, and fearful of being left alone with the limo driver—ended up climbing the six flights to the apartment I shared with Polly, bitching every step of the way.