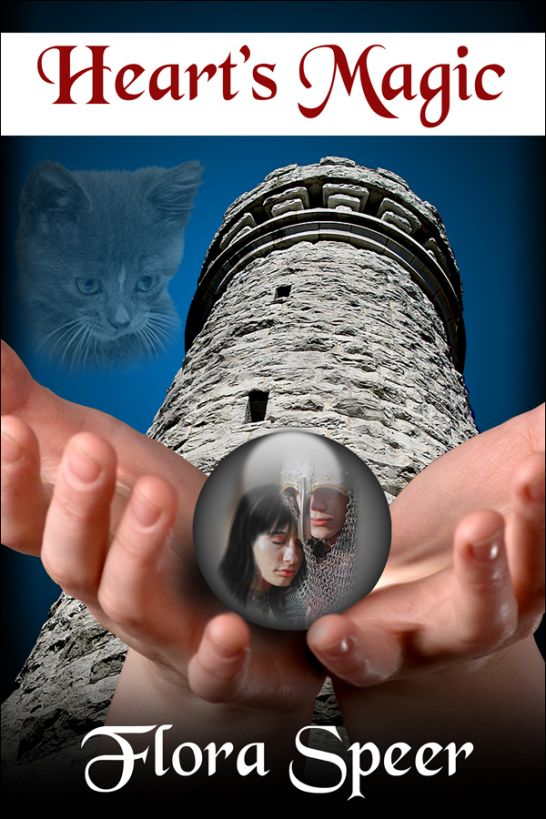

Heart's Magic

By Flora Speer

Smashwords Edition

Copyright © 1997, by Flora Speer

Cover Design Copyright 2011 by

http//DigitalDonna.com

Smashwords Edition License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal

enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to

other people. If you would like to share this book with another

person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If

you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not

purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com

and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work

of this author.

In early March of the Year of Our Lord 1122,

two men rode northeastward along a forest path from Nottingham,

England, into Lincolnshire. Both were identically cloaked and

hooded against the damp chill and their black stallions might have

been twins, yet there were differences between the men. The one who

was taller and more muscular rode with a certain boldness, as if he

knew he had every right to be where he was and even more right to

be at his destination when he finally reached it. The second man,

shorter and more slender than his companion, rode surrounded by an

aura of silence and a peculiar reserve.

The pair traveled without guards in a part of

England not notable for its safety. The rest of their company had

been left behind at Nottingham with the order to wait there. The

giving of that order had generated a remarkably vigorous discussion

around the table of the tavern where they had all spent the

previous night. A nobleman’s retainers did not often dare to

dispute their master’s decisions. This nobleman’s companions were

more his friends than his servants and so they had felt themselves

free to object to the daring scheme he proposed to follow.

“I wish you would reconsider, my lord,” the

older squire, Hidern, had cried. “If you are found out, you will be

consigned to the lowest dungeon in the castle.”

“Or killed outright,” added the younger

squire, Bevis, who harbored a tendency toward lurid notions.

“And then conveniently forgotten, should

anyone ask after you,” Hidern finished.

“It’s best that I travel alone and

unrecognized during this first excursion,” the tall nobleman

insisted. “The rumors you two and Hugh heard while we were at court

only confirm what King Henry told me during my audience with him.

All is not well at Wroxley Castle.”

The nobleman did not think it appropriate to

add that the king blamed himself for whatever problems had arisen

at Wroxley. Devastated by the death of his two sons in a shipwreck

in the autumn of 1120, a still-grieving Henry had agreed to the

current arrangements for Wroxley in the following January and

without much thought on the matter—a hasty decision he repented

now, more than a year later.

“A certain feeling of insecurity at Wroxley

would be quite natural.” The speaker was the fourth man at the

tavern table. Of medium height and slender build, with straight

black hair and dark eyes, his features were so bland that they were

always immediately forgotten after he had left a scene. This

person’s accent was an odd one, unfamiliar even to men who had in

recent years mixed with the men—and the women—of distant countries.

The squires and the nobleman’s men-at-arms knew him as Hugh and,

trusting their leader, they assumed Hugh would not have been

granted the nobleman’s friendship were he not worthy of it.

Furthermore, during their travels together they had found Hugh to

be honest and dependable. Thus, they gave him their full attention

as he continued. “When the baron of a castle dies, there must be

concern about the future amongst the folk who live in that castle

or on the nearby lands. In this case, with the heir absent in the

Holy Land, the people of Wroxley will no doubt be wondering when—or

if—that heir will come home, and what will happen to them until he

does.”

“And if the newly confirmed baron of Wroxley

arrives in full panoply, with banners flying and men-at-arms behind

him, do any of you think the truth of the old baron’s death will

ever be told?” asked the leader of the group. “If only half the

rumors are true, the inhabitants of Wroxley will not dare to reveal

the events of the past year and a half. If the stories we have

heard are fact and not imaginary, then for the new baron to ride in

as if he expected to be welcomed home would only result in death to

many of those same folk who are still loyal to the old baron’s son.

We do not want a battle. The use of force is acceptable only after

all other methods have failed.”

“Well spoken,” said Hugh with a faint smile.

“You always were a good student.”

“For myself, I would prefer more

straightforward means. I see nothing wrong with a good battle.” The

squire, Hidern, paused as if wrestling with an alien concept before

he continued. “You have never failed us before, my lord. Bevis and

I will not quarrel with you over your plans. But know that if you

and Hugh do not return from Wroxley or send us word within the time

you have allotted, then we will investigate and if we discover that

you are in trouble, we will at once send word to King Henry.”

“Who will not be able to raise troops and

move them to Wroxley in time to be of any help to me,” his master

told him. “The king warned me of the problems I could expect to

encounter. Indeed, I have been well and truly warned by him, by

both of you, and by the friends I have at court. I do not undertake

this campaign unaware of the risks.”

“But you are undermanned,” Bevis persisted,

voicing the chief concern of both squires. “Please, my lord, let us

go with you. We can leave the men-at-arms behind if you want, but

for you and Hugh to enter that castle alone is folly.”

“No.” The single word was gentle enough, yet

it was spoken in so firm and commanding a tone that all protest

ceased from that moment on.

Later, while the squires were occupied with

the preparations their master had ordered for his journey, a more

private conversation occurred in the room the leader of the group

had taken for himself.

“The others don’t know all of it, Hugh.”

“I never imagined they did.” Away from public

gaze, Hugh’s features had assumed a more definite cast. His dark,

almond-shaped eyes shone with intelligence and the unlined skin of

his face lay taut over the exotic shape of an alien bone structure.

Hugh’s low voice still held the foreign inflections he seldom

bothered to disguise. “Since you have raised the subject, my

friend, I assume the time has come for us to speak of magic and of

unnatural events.”

“Magic,” Hugh’s companion repeated. “I have a

premonition that I am going to need your art, and your strength, if

I am to succeed. It’s why I have asked you to go to Wroxley with

me. I want a man by my side whom I can trust completely, who will

not lose heart at the touch of magic.”

“You will also need a name other than your

own,” said Hugh.

When morning came Hidern and Bevis armed

their lord, though not as strongly as they would have liked, and

packed a bit of food into the saddlebags, and then they stood

outside the inn watching while their master and his friend rode

away through the twisting streets of Nottingham.

The early morning sunshine vanished by

afternoon behind ominous gray clouds. As the hours wore on the

clouds thickened and lowered into fog. A light drizzle began to

fall. With every mile that shortened the distance between the

travelers and Wroxley Castle the dampness seeped a little deeper

into the very bones of the two men. Still, they pressed on,

determined to reach their destination before nightfall.

“Not at all like Jerusalem, is it?” the

nobleman said with a rueful laugh. “Until today I had all but

forgotten the weather of my youth, when I was so accustomed to fog

and rain that I scarcely noticed either.”

“This climate is certainly different from

others I have encountered,” Hugh responded. “Fog and rain are

conducive to fantastic tales of ghosts and magic and wicked

deeds.”

“Do you think the stories we heard while at

court were fabulous?” his companion asked. “Or do you believe

them?”

“I have not enough evidence to allow me to

form a reasonable opinion on the subject,” Hugh said. “We are yet

too far from Wroxley, and I am unfamiliar with the castle. Still,

from what we have heard, I do believe the prospects of furthering

my education while there are favorable.”

“I have no doubt,” said the other man with a

chuckle that contained little true mirth, “that before long, we

will both learn more than we expect or care to know about wicked

deeds.”

Wroxley Castle.

It was a small thing and perfectly round, its

gleaming surface smoothly polished. Made of crystal so clear that

it appeared to be a raindrop, the sphere fit snuggly into the palm

of Mirielle’s left hand. It had been a present from her nurse,

Cerra, on Mirielle’s tenth birthday, given to her because Cerra

said that Mirielle had the gift of inborn magic.

Most of the time when Mirielle looked into

the globe she saw nothing but the clear crystal. However, there was

an almost invisible inclusion, a tiny flaw at the exact center of

the sphere, one point at which the crystal was not perfect.

Occasionally, when Mirielle turned the sphere in just the right

way, light would strike off the inclusion. At such times she would

see a swirl of clouds in the crystal. On very rare occasions, she

could discern the figure of a man in a dark cloak. The man’s face

was always hidden from her, but whenever his image appeared, an

important change occurred in her life.

She had seen the mysterious image before the

deaths of her parents and Cerra, and had seen it again on the night

before her cousin, Brice, had knocked on the door of her parent’s

manor house to rescue her from her cold-hearted uncle’s plan to

consign her to a convent rather than provide a dowry for her. Brice

had demanded that Mirielle be made his ward and her uncle had been

glad enough to hand over guardianship of the orphaned niece who was

of no use to him.

Some years later Mirielle had seen the man in

the crystal once more, just before she and Brice had left North

Wales to move to Wroxley Castle, where Brice was to become the new

seneschal. And she had seen the vision in the crystal shortly

before Brice had announced that he was making her the chatelaine of

Wroxley.

Now, on this late winter morning, compelled

by a desire she did not understand, Mirielle had taken the crystal

globe in her hand—in her left hand, as Cerra had instructed in the

very first lesson she had taught to Mirielle on the methods by

which the inborn magic could be controlled and directed so it would

benefit others rather than inflicting evil.

The crystal was cool against Mirielle’s palm.

She sent her thoughts into the sphere, finding and then

concentrating on the imperfection she could just barely see.

Without thinking, she moved, turning toward the window until the

fog outside appeared to enter the room and fill the globe with gray

light…and the man appeared, muffled as usual in his dark cloak.

A tremor passed through Mirielle’s body. Her

hand shook a little, the motion disturbing the scene within the

crystal so that, for a moment, she thought she saw not one, but two

men, and she thought they were on horseback.

“It cannot be! The vision never changes.”

Mirielle’s surprised exclamation wakened her companion. Snuggled

into the bed in a fold of the quilt, a small gray cat stirred,

stretching. In the shadowy room Mirielle sensed rather than saw the

movement. It was enough. Her concentration was broken and the image

in the crystal globe vanished.

Damp morning air filtered in through the

window. The room was cold, the fuel in the charcoal brazier that

warmed it having burned away during the night. Shivering, Mirielle

knelt at the foot of the bed to wrap the sphere in the piece of

silk she used to prevent the crystal from being scratched. She put

the treasured object away in the clothes chest and shut the lid.

Deep in thought, she stayed where she was until the cat walked

across the coverlet to rub its face against her shoulder. Mirielle

gathered the cat into her arms.

“Minn, who is that man I see?” she whispered

to her pet. “Why did the scene change just then, when it has never

changed before?

“‘In danger lies the seed of change; in

change lies the seed of opportunity.’ Now, who put that saying into

my thoughts? Certainly Cerra never did. She believed in holding to

the ancient ways and did not like change.”

Mirielle sat on the edge of her bed, her hand

gone still on Minn’s back while she thought about her old nurse

Cerra, who had taught her young charge all she knew of herbs and

healing, and of certain other skills that must never be revealed

save to another who was also a practitioner. Or a pupil, as

Mirielle had been, eager to learn, eager to practice the Ancient

Art.