Heaven: A Prison Diary (2 page)

Read Heaven: A Prison Diary Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

‘However,’ he

says, again before I can respond, ‘if that’s what you want, I’ll have a word

with my opposite number at Spring Hill and see if she can help.’

Once Mr New has

completed his discourse, we go downstairs to meet Matthew, the current orderly.

Matthew is a shy young man, who has a lost, academic air about him. I can’t imagine

what he’s doing in prison. Despite Mr New talking most of the time, Matthew

manages to tell me what his responsibilities are, from making tea and coffee

for the eleven occupants of the building, through to preparing induction files

for every prisoner.

He’s out on a

town leave tomorrow, so I will be thrown in at the deep end.

Dean grabs my

laundry bag and then accompanies me to supper, explaining that orderlies have

the privilege of eating on their own thirty minutes ahead of all the other

inmates.

‘You get first

choice of the food,’ he adds, ‘and as there are about a dozen of us,’

(hospital, stores, reception, library, gym, education, chapel and gardens; it’s

quite a privilege). All this within twenty-four hours isn’t going to make me

popular.

DAY 91

WEDNESDAY 17 OCTOBER

200

1

I wake a few

minutes after five and go for a pee in the latrine at the end of the corridor.

Have you

noticed that when you’re disoriented, or fearful, you don’t go to the lavatory

for some time? There must be a simple medical explanation for this. I didn’t

‘open my bowels’ – to use the doctor’s expression – for the first five days at

Belmarsh, the first three days at Wayland and so far ‘no-go’ at NSC.

Dean turns up

to take me to breakfast. I may not bother in future, as I don’t eat porridge,

and it’s hardly worth the journey for a couple of slices of burnt toast. Dean

warns me that the

press are

swarming all over the

place, and large sums are being offered for a photo of me in prison uniform.

Should they get a snap, they will be disappointed to find me strolling around in

a T-shirt and jeans. No arrows, no number, no ball and chain.

At reception, I

ask Mr Daff if it would be possible to have a clean T-shirt, as my wife is

visiting me this afternoon.

‘Where do you

think you fuckin’ are, Archer, fuckin’ Harrods?’

As a new

prisoner, I continue my induction course. My first meeting this morning is in

the gym. We all assemble in a small Portacabin and watch a ten minute

blackand-white video on safety at work. The instructor concentrates on lifting,

as there are several jobs at NSC that require you to pick up heavy loads, not

to mention numerous prisoners who will be pumping weights in the gym. Mr

Masters, the senior gym officer, who has been at NSC for nineteen years, then

gives us a guided tour of the gym and its facilities. It is not as large or

well equipped as Wayland, but it does have three pieces of cardiovascular kit

that will allow me to remain fit – a rowing machine, a step machine and a

bicycle. The gym itself is just large enough to play basketball, whereas the

weights room is about half the size of the one at Wayland. The gym is open

every evening except Monday from 5.30 pm to 7.30 pm, so you don’t have (grunt,

grunt – the pigs are having breakfast) to complete the programme in a given

hour. I hope to start this weekend, by which time I should have found my way

around (grunt, grunt). Badminton is the most popular sport, and although NSC

has a football team, the recent foot-andmouth problems have played havoc when

it comes to being allowed out onto the pitch (grunt, grunt).

Education.

We all meet in the chapel. The education officer

takes us through the various alternatives on offer. Most of the new inmates sit

sulkily in their chairs, staring blankly at her. As I have already been

allocated a job as the SMU orderly, I listen in respectful silence, and once

she’s finished her talk, report back to my new job.

Matthew is away

on a town visit today, but I quickly discover that the SMU job has three main

responsibilities:

a.

Making tea and

coffee for the eleven staff who regularly work in the building, plus those who

drop in to visit a colleague.

b.

Preparing

the files for new inductees so that the officers have all their details to

hand: sentence, FLED (full licence eligibility date), home address, whether

they have a home or job to go to, whether they have any money of their own,

whether their family want them back.

c.

Preparing

prisoners’ forms for visits, days out, weekend leave, work out and

compassionate or sick leave.

It will also be

part of my job to see that every prisoner is sent to the relevant officer,

according to his needs. Mr Simpson, the resident probation officer tells me,

‘I’ll see anyone if I’m free, otherwise ask them to make an appointment,’

allowing him to deal with those prisoners who have a genuine problem, and avoid

those who stroll in to complain every other day.

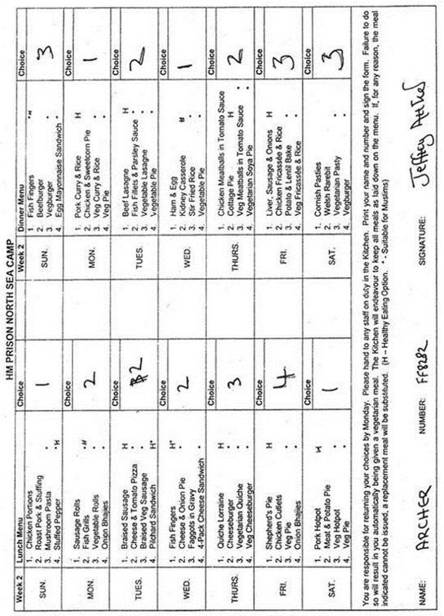

I go to lunch

with the other orderlies. The officer in charge of the kitchen, Wendy, tells me

that NSC was commended for having the best food in the prison service. She

says, ‘You should try the meat and stop being a VIP [vegetarian in prison].’

Wendy is a sort of pocket-sized Margaret Thatcher. Her kitchen is spotless,

while her men slave away in their pristine white overalls leaving one in no

doubt of their respect for her. I promise to try the meat in two weeks’ time

when I fill in my next menu voucher. (See overleaf.)

Now I’m in a

D-cat prison, I’m allowed one visit a week. After one-third of my sentence has

been completed, other privileges will be added. Heaven knows what the press

will make of my first town visit. However, all of this could change rapidly

once my appeal has been heard. If your sentence is four years or more, you are

only eligible for parole, whereas if it’s less than four years, you will

automatically be released after serving half your sentence, and if you’ve been

a model prisoner, you can have another two months off while being tagged

2

Back to today’s visit.

Two old friends, David Paterson and

Tony Bloom, accompany Mary.

The three of

them turn up twenty minutes late, which only emphasizes how dreadful the

250-mile round journey from London must be. Mary and I have thirty minutes on

our own, and she tells me that my solicitors have approached Sir Sydney

Kentridge QC to take over my appeal if it involves that Mr Justice Potts was

prejudiced against me before the trial started. The one

witness

who could testify, Godfrey Barker, is now proving reluctant to come forward. He

fears that his wife, who works at the Home Office, may lose her job. Mary feels

he will do what is just. I feel he will vacillate and fall by the wayside. She

is the optimist, I am the pessimist. It’s usually the other way round.

During the

visit, both Governor Berlyn, and PO New stroll around, talking to the families

of the prisoners. How different from Wayland. Mr New tells us that NSC has now

been dubbed ‘the cushiest prison in England’

(

Sun

), which he

hopes will produce a better class of inmate in future; ‘The best food in any

prison’ (

Daily Star

); I have ‘the

biggest room in the quietest block’ (

Daily

Mail

); and, ‘he’s the only one allowed to wear his own clothes’

(Daily Mirror)

. Not one fact correct.

The hour and a

half passes all too quickly, but at least I can now have a visitor every week.

I can only wonder how many of my friends will be willing to make a seven-hour

round trip to spend an hour and a half with me.

Canteen.

At Wayland, you filled in an order form and then

your supplies were delivered to your cell. At NSC there is a small shop which

you are allowed to visit twice a week between 5.30 pm and 7.30 pm so you can

purchase what you need – razor blades, toothpaste, chocolate, water,

blackcurrant juice and most important of all, phonecards.

I also need a

can of shaving foam as I still shave every day.

What a

difference a D-cat makes.

I go across to

the kitchen for supper and join two prisoners seated at the far end of the

room. I select them because of their age. One turns out to be an accountant,

the other a retired insurance broker. They do not talk about their crimes. They

tell me that they no longer work in the prison, but travel into Boston every

morning by bus, and have to back each afternoon by five. They work at the local

Red Cross shop, and earn £13.50 a week, which is credited to their canteen

account. Some prisoners can earn as much as £200 a week, giving them a chance

to save a considerable sum by the time they’re released. This makes a lot more

sense than turfing them out onto the street with the regulation £40 and no job

to go to.

I join Doug at

the hospital for a blackcurrant juice, a McVitie’s biscuit and the Channel 4

news. In Washington DC, Congress and the Senate were evacuated because of an

anthrax scare. There seem to be so many ways of waging a modern war. Are we in

the middle of the Third World War without realizing it?

I return to the

north block for roll-call to prove I have not absconded.

3

Doug assures

me that it becomes a lot easier after the first couple of weeks, when the

checks fall from six a day to four. My problem is that the final roll-call is

at ten, and by then I’ve usually fallen asleep.

DAY 92

THURSDAY 18 OCTOBER

200

1

Because so much

is new to me, and so much unknown, I am still finding my way around.

Mr Hughes and Mr

Jones, the officers in charge of the north block, try to deal quickly with

prisoners’ queries and, more important, attempt to get things ‘sorted’, making

them popular with the other inmates. The two blocks resemble Second World War

Nissen huts. The north block consists of a 100-yard corridor, with five spurs

running off each side. Each corridor has nine rooms – you have your own key,

and there are no bars on the windows.

Two prisoners

share each room. My roommate David is a lifer (murder), and has the largest

room: not the usual five paces by three, but seven paces by three. I have

already requested a transfer to the nosmoking spur on the south block, which

tends to house the older, more mature prisoners. Despite the

News of the World

headline, ‘Archer demands

cell change’, the nosmoking rule is every prisoner’s right.

However,

Governor Berlyn is unhappy about my going across to the south block because

it’s next to a public footpath, which is currently populated by several

journalists and photographers.

The corridor

opposite mine has recently been designated a no-smoking zone, and Mr Berlyn

suggests I move across to one of the empty rooms on that spur. As the prison is

presently low in numbers, I might even be left on my own. Every prisoner I have

shared a cell with has either sold his story to the tabloids, or been subjected

to front-page exposés – always exaggerated and never accurate.

My working day

as SMU orderly is 8.30 am to 12, lunch, then 1 pm to 4.30 pm. I arrive

expecting to find Matthew so he can begin the handover, but Mr Gough is the

only person on parade. He has his head down, brow furrowed, staring at his

computer. He makes the odd muttering sound to himself, before asking politely

for a cup of tea.

9.00 am

Still no sign of

Matthew. I read through the daily duties book, and discover that among my

responsibilities are mopping the kitchen floor, sweeping all common areas,

vacuuming the carpets and cleaning the two lavatories as well as the kitchen.

Thankfully, the main occupation, and the only thing that will keep me from

going insane, is dealing with prisoners’ queries. By the time I’ve read the

eight-page folder twice, there is still no sign of Matthew, which is beginning

to look like a hanging offence.

If you are late

for work, you are ‘nicked’, rare in a D-cat prison, because being put on report

can result in loss of privileges – even being returned to a C-cat – according

to the severity of your offence. Being caught taking drugs or absconding is an

immediate recategorization offence. These privileges and punishments are in

place to make sure everyone abides by the rules.

Mr New, the

principal officer, arrives just as Mr Gough enters the room.

‘Where’s

Matthew?’ he asks.

I then observe

the officers at their best, but the Prison Service at its most ineffective.

‘That’s why I

came looking for you,’ says Mr Gough. ‘Matthew reported back late last night’ –

an offence that can have you transferred to a C-cat, because it’s assumed that

you’ve absconded – ‘and he was put on report.’ The atmosphere immediately

changes.