Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (31 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

I’m restless, he said to Talia. And that’s the only virtue of living in fear. There’s no such thing as monotony, tedium, or ennui.

He was surprised he’d confided in Talia, and Talia caught his surprise. She smiled and took his bishop.

You must be very bored to think of all those words, she said. And you’ve just lost two games in a row. Why don’t you spend some time with the Scribes?

They’d ask questions, said Asher.

Don’t answer them.

Talia smiled again, and he smiled back, realizing he’d forgiven her and Mikhail about the letter to Heidegger, which—even if absurd—had saved his life. He carried a detective story and a treasured blue and white mug from Holland to the main room where he got a desk as well as pillows so he could sit in a corner and read. The Scribes saw the numbers on his arm and remembered, as they had with Daniel, how close they’d come to that place themselves and how willing they’d be to come close again just to keep him safe. They also decided not to annoy him by asking about chimneys. Except for Parvis Nafissian, who wanted to annoy him because he was still angry with Daniel for taking Maria away.

Of course there were chimneys, said Asher. They were the hardest workers at Auschwitz. They were alert, even lively.

Sophie Nachtgarten smiled at him.

Lively chimneys, she said. Now there’s an interesting idea. By the way, you should get a coat so we can go outside.

From people who are dead? said Asher. Do you answer their letters now?

Dear Frau So-and-So…. Not only is your husband fine, but I happen to be wearing his coat!

Dear Frau So-and-So…. Not only is your husband fine, but I happen to be wearing his coat!

Listen, said Sophie. There’s not one of us who hasn’t scrambled and clawed our way to get here. There’s not one of us who hasn’t lied or faked languages or done whatever we could to stay away from where you’ve been. So what if we wear gloves and hats and scarves that belong to people who are dead or have lice eating into their skin?

He watched her grab at the coats with increasing fury. He heard tears in her voice.

I lost my entire family, she said. My mother and father, my two brothers, their wives, and my four-year-old niece. I think I should be allowed to choose a coat.

While she spoke, she’d been rummaging through the coats until she found a leather jacket with a fur collar.

This might be interesting on you, she said. Once more her voice was calm.

After what you just told me? No.

Just try it, said Sophie.

Asher put on the jacket, and Sophie stood back to look at him.

It fits you, she said. You can pretend you’re a bomber with the Allies.

Not unless I have a scarf, said Asher.

Then I’ll get you one, said Sophie, pulling a white scarf from a burlap bag.

Perfect! she said. You can pretend you’re a British pilot on his day off.

Should I play cricket? said Asher.

Cribbage would be fine, said Sophie. She took his arm. Please take me for some air. Let’s go to the well.

Asher refused. As much as he distrusted this compound in purgatory, he thought his upsetting version of eternity might be better than being shot, or hung, in the forest. Besides, his very presence put everyone at risk. He should remain hidden below the earth.

But there was an upwelling of nos, and Niles Schopenhauer said Asher had come from a place they’d all barely escaped, and they owed it to him to make sure he got fresh air.

Asher said they might not be so heroic if they’d actually been to Auschwitz, and he followed Sophie to the cobblestone street, avoiding the miserable little group on the bench. The lift rumbled as it took them from the earth. Asher remembered gunshots.

Sophie led Asher up the incline, through the shepherd’s hut, to the snow-covered clearing. Asher followed slowly, looking at the forest. Sophie urged him on. It was the first time he’d seen real sky in months. It was an extraordinary blue with white clouds that moved swiftly, miraculously. Not long ago he’d felt like a scrap covered with rags, lighter than the wind. Now he could feel he had weight, substance, gravity. He touched his arms, his legs, and his face. He felt taller than the trees.

Sophie kept beckoning until he got to the well. And even though his face quivered in the water, Asher could see that it was no longer the face of a skeleton, but the face of a living man. Sophie handed him the big tin dipper.

Drink! she said.

Asher drank. Water had never tasted so good.

Dear Diane,You probably know about the insurrection. Some of the prisoners repairing uniforms found a way to break into the armory. Then the timing was off and they had to put the guns back. Two days later they snuck them again. All of them were killed, but before they were killed they shot the officer I had to sleep with. He was protecting my parents, so I worry—Love,Homa

When he came back from the well, Asher barely looked at Elie, who was sitting at her enormous desk. She was part of what came before his life snapped in half, and he didn’t want her to be part of it now. Indeed—in some odd boomerang of the mind—he wondered if their affair had something to do with his wife joining the earliest Resistance, which later resulted in her death. And even though he’d met Elie after his wife disappeared, he decided it had, and he didn’t care if Elie had anything to do with his being in this dungeon instead of Auschwitz. He stared at her over his detective story and remembered everything about their affair that had been unpleasant: Sneaking to cafés where people from the university couldn’t find them. Impaling himself on a filing cabinet in his office when they made love. It had rained a lot during that time, and they were always taking cover under awnings. Once Elfriede Heidegger walked by and saw them. Ever since she had treated him with disdain.

He also wondered why Elie Kowaleski deserved adoration when other people were dying like flies. And how a discreetly rebellious student of linguistics had been reborn as a star in this underground world. When she came back from a mission, people applauded. And sometimes, for no apparent reason, people toasted her. What had she done to deserve it? How did she get so much food?

Yet when Gerhardt Lodenstein sat by Elie’s desk—as he did now—Asher watched their every move. They often seemed passionately worried, and the intensity of their absorption made Asher realize he was lonely because it had been a long time since he’d been intimate enough to share worry with another person. And even though he’d long forgotten Elie, he began to feel jealous of Gerhardt Lodenstein—a feeling that upset him because Lodenstein had saved his life, Daniel’s life, and had nearly gotten killed in the process.

Now he got up and stood near Elie’s desk, pretending to be fascinated by the jumble shop against the wall. He couldn’t hear what she and Lodenstein were saying but listened to their tone. It was clearly passionate, with a timbre of anxiety, even anger.

He turned around and met Lodenstein’s eyes. Lodenstein smiled—a smile of truce and good will.

Of course he knows

, Asher thought.

And what’s more, it doesn’t matter to him that much.

Of course he knows

, Asher thought.

And what’s more, it doesn’t matter to him that much.

He hardly ever thought about the past during the war because he was so preoccupied with Daniel’s safety and his wife’s disappearance. But Elie’s face opened a floodgate to times long before the war, times when something as simple as a walk could make him happy. He remembered his wife reading in the evening, light against her face, and Daniel crawling into bed to hear a story. He remembered snow on skylights, warm air after winter, the first lectures of fall. Everything was a pathetic stand-in for what his life had been since then—even this underground world. And every time he saw Elie, he was pushed against this earlier world that he wanted to forget because he had been happy.

He barely smiled back at her and returned to his cluster of pillows, where he buried himself in another detective story and thought about the time he’d been relegated to

before

the war: He thought about his wife playing Mozart. Daniel doing homework instead of this absurd preoccupation with typewriters. And he thought about his house filled with plants and books. He felt irritated with the Scribes, who behaved like children—writing in secret codes, inventing languages, exalting in a spirit of privilege and discontent. He was tired of seeing Lodenstein’s rumpled green sweater and eccentric compass. He even hated Mikhail and Talia Solomon and their preoccupation with chess, which seemed ponderous. As well as Dimitri, who liked to collect stamps.

before

the war: He thought about his wife playing Mozart. Daniel doing homework instead of this absurd preoccupation with typewriters. And he thought about his house filled with plants and books. He felt irritated with the Scribes, who behaved like children—writing in secret codes, inventing languages, exalting in a spirit of privilege and discontent. He was tired of seeing Lodenstein’s rumpled green sweater and eccentric compass. He even hated Mikhail and Talia Solomon and their preoccupation with chess, which seemed ponderous. As well as Dimitri, who liked to collect stamps.

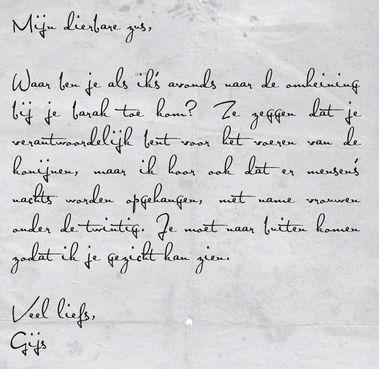

My dearest sister,Where are you when I come to the edge of your cellblock at night? People say you’re in charge of feeding the rabbits, but I’ve heard of hangings by candlelight, especially of women under twenty. I need you to be outside so I can see your face.Love,Gijs

One day, when Asher was in the throes of such mean spirited thoughts, La Toya said he wanted to discuss something where no one else could hear them. Asher said he would never go to the vent above the water closet where people sat in a dark cave and heard others piss and shit. So La Toya suggested the well.

It was early spring, and snow was melting. Asher saw grass in the clearing and buds on the ash trees. There was no more snow that could make things infinitely reversible. It was a world without camouflage. They navigated mud puddles, and La Toya asked what was going on between him and Elie Schacten. Asher tightened his hold on the pail.

Other books

The Paradise Guest House by Ellen Sussman

Close to Hugh by Marina Endicott

Candace Camp by A Dangerous Man

It's A Shame by Hansen, C.E.

Sorcerer of the North by John Flanagan

Afterlands by Steven Heighton

A False Dawn by Tom Lowe

Beating the Devil's Game: A History of Forensic Science and Criminal by Katherine Ramsland

Eat the Document by Dana Spiotta