Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (6 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

The officer handed Elie a pine box overflowing with glasses. Each had a white tag on an earpiece and a different name on each tag. One pair was marked

für Martin Heidegger

. Elie stared at Asher Englehardt’s handwriting.

für Martin Heidegger

. Elie stared at Asher Englehardt’s handwriting.

You need to deliver the glasses

and

a letter, said the officer.

and

a letter, said the officer.

I understand, said Elie, still careful to sound calm. By the way—do you know what happened to the optometrist?

Do you think he went on vacation to the Badensee? said the officer. The SS man watching out for him was shot, and he got sent to Auschwitz. He ran his finger across his throat—the slash of a knife. Maybe his mother was Aryan, but these days no one’s lucky. And that Angel of Auschwitz got just one chance.

Elie nodded. The officer stubbed out his cigarette.

Do you want anything else? he asked, pointing to the walls.

We can always use coats. And another kilo of chocolate.

The officer carried the coats across the snow, and Elie carried everything from Asher Englehardt’s optometry shop, including Heidegger’s glasses and his letter to Asher, the last sentence of which read:

How could either of us have known you would be the person to make me real glasses—that unwitting source of my falling out of the world?

Elie, who had met Heidegger and read Heidegger, understood exactly what he meant. But she agreed that the letter was crazy. They got to her jeep; she let the officer kiss her on the lips again and hold her longer than she would have liked. Then she drove to the North German woods, thinking about Goebbels’s orders. At the clearing, she shone her flashlight on the photographs. She folded them in half and pushed them deep into her pocket.

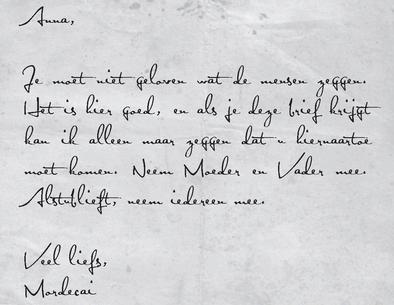

Anna,You mustn’t believe what people are saying. This place is good, and if you get this letter, I can only tell you to come here. Bring mother and father and the children. Please, bring everyone.Love,Mordecai

When Elie walked into the hut, Lodenstein was wearing his Navy trench coat and toying with his compass on the wooden table. It was a liquid compass from the British Royal Navy—he had found it in a shop before the war. The compass was used on ships, but Lodenstein took pleasure in using it on land. It helped him feel close to the sea, especially the horizon where he saw the sun and moon over far-flung water. Sometimes he joked to Elie:

Suppose the earth is flat after all? If you’re near the sea, you can escape.

Suppose the earth is flat after all? If you’re near the sea, you can escape.

He reached for the orders and Heidegger’s letter and read them a few times to see if they were coded. But the messages were exactly what they were meant to be: From Heidegger, brilliance and bombast. From Goebbels’s office, orders to deliver Heidegger’s glasses and a letter without a trace of where they’d come from.

A hausfrau’s leading Goebbels around, said Elie.

But even generals can’t do that, said Lodenstein.

It’s Heidegger’s wife, said Elie. A great example of

Kinder

,

Küche, und Kirche

.

Kinder

,

Küche, und Kirche

.

I thought her

kinder

left home.

kinder

left home.

Heidegger hasn’t.

Lodenstein laughed, and Elie didn’t mention she’d once been to a party at the Heideggers and gotten Frau Heidegger’s recipe for bundkuchen.

Maybe it’s all made up, said Lodenstein. Or maybe they want a reason to shoot me.

No one wants a reason to shoot you, said Elie. And I’m pretty sure the optometrist is real.

Why are you sure? said Lodenstein. People invent themselves like flies these days. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone invented us.

Maybe they did, said Elie. But I happen to have met Martin Heidegger.

I thought you read in linguistics.

I did, said Elie. But everybody knew each other.

There was a cracked mirror on the fireplace, and Elie walked to it and worked the ribbon in her hair. When she’d tied a bow that met her standards, she said:

Heidegger and Asher Englehardt were friends. They wrote each other letters. They met for coffee.

Except now Englehardt’s at a place where no one writes letters. Except the ridiculous ones you read.

Elie came back to the table. Her eyes were preternaturally bright.

Maybe these orders could get Englehardt out, she said.

Listen to me, Elie. People don’t leave Auschwitz.

I know about a few.

Yes. As ashes.

Not always, said Elie. Just a week ago an SS man came to the Commandant and said a prisoner owned a lab and the Reich needed it for the war, and he had to leave Auschwitz to sign the papers. So he did. And guess what? There aren’t any records of the lab, and no one knows the SS officer. People think he wasn’t real. They call him the Angel of Auschwitz.

Who told you that?

The outpost officer.

He’s losing it, said Lodenstein.

But it’s all over the Reich. And Asher Englehardt is the only ventriloquist we’ll ever find.

There are plenty of people who can write a good letter.

Who?

Lodenstein waved his hands. I’m sure we can find one.

But these orders might get him out.

Listen to me, Elie. If we fool around, Goebbels will shoot everyone in the Compound. And these orders aren’t even signed. Anyone could have sent them.

But the glasses are real. And I’ll talk to Stumpf about the letter.

You can try, Lodenstein said. But Major Stumpf is a fool.

That’s exactly why I want to talk to him, said Elie.

Stumpf can never help anybody, said Lodenstein. And it was bad enough that you asked him to the feast.

Dieter Stumpf was the man who lived in the shoebox overlooking the Scribes. He was short and stout and reminded Elie of a shar-pei dog whose skin is all in folds. The shar-pei hadn’t come to Germany, but a Chinese painting of one turned up at the outpost, and Elie took it because it reminded her of Stumpf. The painting was her private joke with Lodenstein.

Stumpf had been Obërst of the Compound until Lodenstein replaced him. For reasons no one had bothered to explain, he’d had to move from the room above the earth to a shoebox accessed by winding steps. The shoebox was his bedroom as well as his office: in addition to a desk it had a mattress, crystal balls, and books about the astral plane.

It also had a large window overlooking the main room of the Compound. Once, rotating guards patrolled the Scribes, but after Germany lost Stalingrad, only Lars was left to guard the forest, and Stumpf had to patrol. He rationalized his demotion by imagining he was the only person Goebbels trusted to make sure the Scribes did their work. But secretly he agonized.

Before Stalingrad, Stumpf had been delighted to record answers to the dead and loved his huge metal stamp and big black paw of an inkpad. But the guards had been clever at foreign languages, and Stumpf had never learned one. If the correspondence was in German, Stumpf used his huge metal stamp so vigorously the crystal ball on his desk rattled. But if the letters were in a foreign language, he had no way of knowing whether the Scribes had duped him by writing nonsense. Sometimes his stamp hovered in the air. Sometimes it pounced. At other times he got overwhelmed. Then he heaved down the spiral staircase and told everyone in the main room they were scroungers. His rants went on until someone—a Scribe, or Lodenstein, if he were there—put two fingers in the shape of devil’s horns behind his head. Everyone laughed, the folds in Stumpf’s face sagged, and he crept back to his shoebox, looking so forlorn people felt sorry for him. But only for a while. Being ridiculed was trivial compared to having a gun at your head or seeing your child shoved into a cattle car.

Dear Mother,I hope you can read this letter. They have asked that I write in pure German, not our dialect. Perhaps I will help out with translations. Lotte and I both miss you.Love,Franz

Stumpf, who was still under the illusion that Lodenstein treated the Scribes like prisoners, despised them because they didn’t respect what he perceived to be the mission of the Compound. They answered only half of what they could have answered in a day and spent the rest of the time writing in diaries and holding raffles for Elie’s old room: they raffled cigarettes, sausages—it didn’t matter what, as long as it amused them. Meanwhile, thousands of letters from the camps arrived each month, and Stumpf had gotten word from Goebbels’s office that there would be an inspection in a fortnight. There were too many dead and no way all the letters could be answered. So, much against his principles, he was planning to bury thousands of letters in the rye field of his brother’s farm near Dresden. He was sure all the dead deserved answers and was upset by this decision, but it was better than being shot. Stumpf’s sacrifices to the dead stopped when it came to joining them.

Other books

When Bruce Met Cyn by Lori Foster

Sagebrush Bride by Tanya Anne Crosby

Just Another Job by Brett Battles

Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy

The Rainbow Bridge by Aubrey Flegg

Unlocking the Sky by Seth Shulman

The Diamond Affair by Carolyn Scott

White Wolves MC: A BWWM Interracial Romance by Ella Douglas

The Prince of Midnight by Laura Kinsale