Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (15 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

Lawrence accomplished what he set out to do. He spread the news of his presence throughout Syria, even going to the trouble of blowing up a railway bridge at Ras Baalbek, on the Aleppo-Damascus line—final proof, if any were needed, that he was in Syria, and that the force he was gathering in Wadi Sirhan was intended for an attack in the direction of Damascus, not Aqaba.

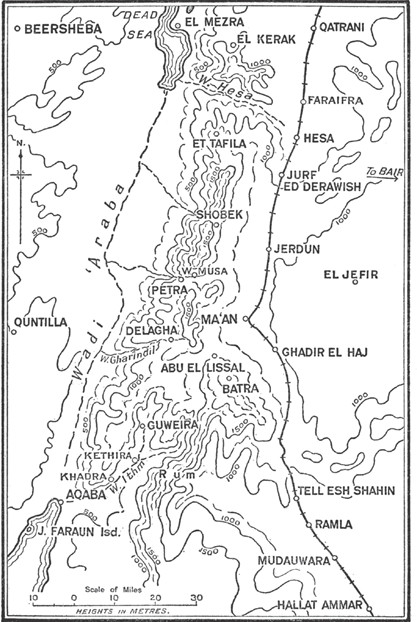

Lawrence arrived back at Nebk on June 16, 1917, to find Auda and Nasir “quarrelling.” He managed to settle the quarrel by the time they set out on June 19 with the 500 men Auda had gathered. Their first march (of two days) was to Beir, in what is now Jordan, where they discovered that the Turks had dynamited the wells. They managed to clear one, but Auda was now wary about what they would find at El Jefer, fifty miles to the southwest across difficult desert terrain, where, if the wells were destroyed, their camels would die. They camped at Beir and sent a scout ahead, while Lawrence rode to the north with more than 100 tribesmen, among them Zaal, “a noted raider,” to attack the railway and ensure that the Turks would be looking in the wrong direction. They rode hard, in “six hour spells,” with only one or two hours of rest between spells. They reached the railway north of Amman and, after watering the camels, moved on hoping to destroy a bridge, only to find that the Turks were busy repairing it. Since Lawrence’s objective was to make the Turks believe he was going toward Azrak, his raiding party continued on andfound a curved stretch of the railway near Minifir. Although hunted by tribesmen in the pay of the Turks and by Turkish infantrymen mounted on mules, Lawrence and his party managed to blow up the railway and leave behind a buried mine to damage or destroy the locomotive when the Turks sent a repair train down from Damascus. They took two Turkish prisoners, deserters, who died of their wounds—there was nothing the raiding party could do for them, though Lawrence left behind, attached to a telegraph pole he had torn down, a letter he wrote in French and German indicating where they could be found.

The party moved on by night and the next day captured a young Circassian

*

cowherd. This posed a problem—it seemed to Lawrence unfair to kill him, but at the same time they could neither take him with them nor turn him loose, since he would certainly tell the Turks of their presence. They were unable to tie him up, since they had no rope to spare, and in any case if he was tied to a tree or a telegraph pole in the desert he would die hideously of thirst. Finally he was stripped of his clothes, and one of the tribesmen cut him swiftly across the soles of his feet with a dagger. The man would have to crawl naked on his hands and knees an hour or two to his home, but the wounds would heal eventually and he would survive.

The incident gives one a picture of Lawrence’s curious mixture of practicality and humanitarianism. Unlike the Arabs he rode with, he was constantly torn between his own system of ethics and their more savage instincts. The tribesmen had no compunction about cutting the throat of a terrified captive after robbing and stripping him. As if to prove this, Zaal led the party, maddened by the sight of a herd of fat sheep—they had been living off a diet of hard dried corn kernels for days—in a raid on a Turkish railway station at Atwi, about fifty miles east of the Dead Sea,where Zaal sniped at and killed a fat railway official on the platform. The tribesmen exchanged rifle fire with the Turks, then plundered an undefended building; drove off the herd of sheep; shot and killed four men who, unluckily for them, arrived on a hand trolley in the middle of all this; set fire to the station; and rode off. The raiding party slaughtered the stolen sheep, gorging on mutton, and even feeding it to their camels, “for the best riding camels were taught to like cooked meat,” as Lawrence notes, adding, with his usual precision, that “one hundred and ten men … ate the best parts of twenty-four sheep.” Then he blew up a stretch of track and they set out on the long journey back to Beir.

Raids like this kept the Turks on edge, while satisfying the Bedouin’s taste for plunder and action. They also acclimatized Lawrence to the ways of the Bedouin, which most British officers found infuriating. The Bedouin had no sense of time; they did not accept orders; they would break off fighting to loot, then ride home with what they had stolen; they thought nothing of stripping and killing enemy wounded; they wasted ammunition by firing feux de joie into the air to announce their comings and goings; when there was food they gorged on it, instead of thinking ahead; when there was water, they drank until their bellies were swollen, instead of rationing it out sensibly; they stole shamelessly, from friend and foe alike; their tribal quarrels and blood feuds made it difficult to rely on them when they were formed up in large numbers; by British standards they were cruel to animals; and they were distrustful of Europeans and Christians, even as allies. In order to lead them, Lawrence had to learn to accept their ways, to share their ribald and teasing sense of humor and their extravagant emotions and love of tall tales, to embrace the extreme hardships of their life, and to understand that because they were intense individualists any attempt to give a direct order to them would be treated as an insult. This was a difficult task—even such great explorers and pro-Arabists as Richard Burton and Charles Doughty had never managed to lead the Bedouin, or be accepted by them as equals—yet Lawrence succeeded, though in doing so, he gave up some part of himself that he never recovered, eventually becoming astranger among his own countrymen. Nobody understood this better than Lawrence himself, who wrote: “A man who gives himself to the possession of aliens leads a Yahoo life…. He is not one of them…. In my case my effort for these years to live in the dress of Arabs, and to imitate their mental foundation, quitted me of my English self, and let me look at the West and its conventions with new eyes, and destroyed it all for me. At the same time I could not sincerely take on the Arab skin: it was an affectation only.”

That was written years later, when his intense fame, and his disappointment at his own failure to get for the Arabs what he had promised them, had embittered Lawrence about the role he played in the war. But there is no reason to believe that he felt this way as he rode back into Beir “without casualty, successful, well-fed, and enriched, at dawn.” He was fêted by Auda and Nasir, and found the rest of the party cheered by a message from the wily Nuri Shaalan that a force of 400 Turkish cavalrymen was hunting for Lawrence’s party in Wadi Sirhan, guided by his own nephew, whom Nuri had instructed to take them by the slowest and hardest of routes.

On June 28 Lawrence set out for El Jefer, despite news that the Turks had destroyed the wells. This turned out to be true, but Auda, whose family property these wells were on and who knew them well, searched out one well the enemy had failed to destroy. Lawrence organized his camel drivers to act as sappers, digging in the unbearable midday heat until they were able to expose the masonry lining of the well, and open it. The Ageyl camel drivers, less resistant to manual labor than the Bedouin tribesmen, then formed a kind of bucket brigade to bring up enough water to take the camels over the next fifty barren miles.

Lawrence sent word ahead to a friendly tribe to attack the Turkish blockhouse guarding the approach from the north to Abu el Lissal, the gateway to the wadi that led down to Aqaba, some fifty miles away. The attack was timed to stop the weekly caravan that carried food and supplies from Maan to all the outposts on the way to Aqaba, and to Aqaba itself. The taking of the blockhouse turned out to be a bloody, botchedaffair, during which the Turks slaughtered Arab women and children in their tents nearby; in retaliation the infuriated Arabs took no prisoners after the blockhouse fell to them, then sent word sent to Lawrence it was in their hands. He set out for Abu el Lissal on July 1, pausing when his party reached the railway line to blow up a long section of track, and sending a small party to Maan to stampede the Turkish garrison’s camels in the night. Despite these precautions, however, a Turkish column advanced on Abu el Lissal, reoccupying the blockhouse.

As Liddell Hart points out, this was Lawrence’s first exposure to the vicissitudes of war—a Turkish relief battalion had arrived in Maan just as the news came that the blockhouse at Abu el Lissal had been attacked. It was an accident, a coincidence, but the result was that the Arab tribesmen abandoned the blockhouse, which they had pillaged and destroyed, and the Turkish battalion set up camp at the well. Lawrence had foreseen this possibility and had an alternative plan in mind—already, he was thinking like generals he admired. It would take time and involve splitting his forces, and possibly serious losses, one part of his strength attacking the Turkish battalion to hold it in position, the other taking an alternative but slower route behind the Turks to Aqaba.

Either way, Lawrence had placed himself in a position from which no retreat was possible. There was no chance that he could take his forces back to Wejh, which was nearly 300 miles south as the crow flies, and more than twice that by any route he could take over the desert. The Turks were already in Wadi Sirhan, and could bring in reinforcements from Maan and Damascus. If they were successful Lawrence and his men would be cut off, surrounded, and killed, the Arabs as traitors to the Ottoman Empire. Lawrence himself, a British officer caught out of uniform in Arab clothing, was sure to be tortured, then hanged as a spy. He had no option but to move forward and seek battle.

It requires a very special kind of courage to advance and attack a larger, well-positioned force when one’s lines of communication and path of retreat have been cut. Much as Lawrence would dislike Marshal Foch when he met Foch at the Peace Conference in Paris in 1919—and rejected the kind of massed frontal attack that had already led to so many million deaths on the western front—he would have agreed with Foch’s most famous military apothegm: “Mon centre cède, ma droite recule; situation excellente. J’attaque!"

*

Through a day of heat that produced waves of mirages, Lawrence led his party toward Abu el Lissal, pausing only to blow up ten railway bridges and a substantial length of the track. At dusk they stopped to bake bread and rest for the night, but the arrival of messengers with the news that a Turkish column had arrived spurred Lawrence on. His men remounted their camels—"Our hot bread was in our hands and we ate it as we went,” he wrote—and rode through the night, stopping at first light on the crest of the hills that surrounded Abu el Lissal to greet the tribesmen who had taken the blockhouse and lost it. Just as there was no going back, Lawrence realized, there was no going forward so long as a Turkish battalion held Abu el Lissal. Even if they could make their way around it, Lawrence’s force would still be bottled up in a valley with Turks at either end. The Arab force dismounted and spread out on the hills around the Turkish campsite, while Lawrence sent someone to cut the telegraph line to Maan. The Turks were, literally, caught napping. From higher ground the Arabs began to shoot down on the Turks, in a firefight that lasted all day. The men kept continually on the move over the rocky, thorny ground, so as not to offer the Turks a fixed target, until their rifles were too hot to touch, and the stone slabs they lay down upon to fire were so superheated by the sun that whatever patch of skin touched them peeled off in great strips, while the soles of their feet, lacerated by thorns and burned by the hot rock, left bloody footprints whenever they moved. Short of water because of the haste in which they had left, the tribesmen suffered agonies of thirst.

By late afternoon Lawrence himself was so parched that he lay down in a muddy hollow and tried to filter the moisture out of the mud by sucking at the dirt through the fabric of his sleeve. There, he was foundby an angry Auda, “his eyes bloodshot, and staring, his knotty face working with excitement,” in Lawrence’s words. “Well, how is it with the Howeitat?” Auda asked, grinning. “All talk and no work?"—throwing Lawrence’s earlier criticism of Auda’s tribe back in his face.

“By God indeed,” Lawrence replied tauntingly, “they shoot a lot and hit little.”

Auda was not one to take criticism (or sarcasm) lightly. Turning pale with rage, he tore off his headdress and threw it to the ground (since as Muslims the Bedouin never go uncovered, this was a significant indicator of Auda’s anger), and ran up the steep slope of the hill calling to his tribesmen to come to him. At first Lawrence thought that Auda might be pulling the Howeitat out of the battle, but the old man stood up despite the constant Turkish rifle fire, glaring at Lawrence, and shouted, “Get your camel, if you wish to see the old man’s work.”

Lawrence and Nasir made their way to the other side of the slope, where their camels were tethered. Here, sheltered from the gunfire, were 400 camel men, mounted and ready. Auda was not in sight. Hearing a sudden, rapid intensification of the firing, Lawrence rode forward to a point from which he could look down the valley, just in time to see Auda and his fifty Howeitat horsemen charging directly down at the Turkish troops, firing from the saddle as they rode. The Turks were forming up for an attempt to fight their way back to Maan when Auda’s bold cavalry charge hit them in the rear.