Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (40 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

Another interesting detail is the

unusual proportion of bog bodies with

physical defects of some kind. One of

the bodies from Lindow Moss had six

fingers, others had spinal problems or

foreshortened limbs, and such people

may have been chosen for sacrifice because they were seen as being physically set apart by the gods. We must

also remember that bogs are treacherous places, and we cannot rule out

the possibility that some of the socalled bog burials are the result of misadventure. People may simply have

fallen in and drowned. Others could

be the remains of paupers or women

who died in childbirth and were buried in unconsecrated ground. This could

be the explanation for the careful

burial of the girl from Meenybradden

in Ireland. Nevertheless, considering

the vast array of possible scenarios,

it is obvious that there can never be

one single explanation for the gruesome but compelling mystery of the

bog bodies.

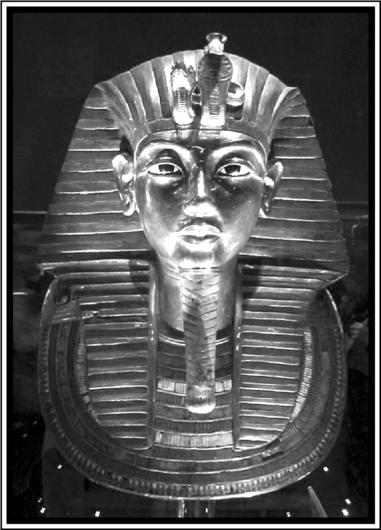

Photograph by Michael Reeve. (GNU Free Documentation License).

The gold funerary mask of Tutankhamun, in the Egyptian Museum of Cairo.

Howard Carter's spectacular discovery in 1922 of the almost intact tomb

of the boy pharaoh Tutankhamun, in

the Valley of the Kings, inspired an

interest in ancient Egypt that endures

to this day. Indeed, the fabulous gold

mask of Tutankhamun has become the

popular image of Egyptian civilization. But these dazzling treasures

have put the actual person behind the

golden mask in the shade. The real life

of the boy king of Egypt was short and

somewhat mysterious; his parentage

remains uncertain as does the date of

his accession to the throne. Until recently, the cause of Tutankhamun's

death was also completely unknownwas it a hunting accident, or did he die

from a disease? Or could he have been

murdered?

Tutankhamun remains a mystery

despite Carter's discovery. The tomb

was full of riches, more than 2000 objects in all, and the mummy of the boy pharaoh was found contained within

three golden coffins. But there was

practically no documentation recovered from within the tomb, which

makes it very difficult to put together

an accurate story of Tutankhamun's

life. It is believed that his parents may

have been the heretic 18th Dynasty

pharaoh Akhenaten, who ruled Egypt

from 1367 B.C. to 1350 B.C. (or 1350 B.C.

to 1334 B.C.) and his mysterious second

wife, Kiya. Akhenaten had taken the

unprecedented and revolutionary step

of replacing the traditional old gods

of Egypt with a single sun god called

the Aten. Thus, Tutankhamun's name

at birth was actually Tutankhaten (Living Image of the Aten) and was only

changed to Tutankhamun (Living Image of Amun) a year or two into his

reign, when polytheism was restored

to Egypt. Tutankhamun seems to have

come to the throne at the age of nine,

perhaps around 1334 B.C., and ruled for

about 10 years. Because the new pharaoh was so young and had no living

female relatives old enough, much of

the considerable responsibility of his

kingships (and his personal upbringing) must have been in the care of Ay,

his chief minister, and Horemheb, commander-in-chief of the army.

Shortly after becoming king,

Tutankhamun married his half-sister

Ankhesenamun, a daughter of

Akhenaten and his first wife, Nefertiti,

and granddaughter of the chief advisor to the king, Ay. There is very little

information about the reign of

Tutankhamun, who ruled first from

Akhenaten's city of Amarna, on the

east bank of the Nile about 250 miles

north of Luxor, before moving to his

new capital at Memphis, 12 miles south

of modern Cairo on the west bank of

the Nile. It was Horemheb and Ay who

were probably responsible for persuading the new pharaoah to relinquish the

religion of Aten, and start to return to

the old ways. Preserved on his restoration stelae-at the Temple of

Karnak at Thebes-are descriptions of

the steps taken by Tutankhamun to

bring back the old gods and traditions,

which included founding a new priesthood and embarking on building and

restoration programs at the temples

of the ancient gods.

The pharaoh and his wife did have

two known children, both stillborn

girls, whose mummies were discovered in his tomb. The only other fact

that is known is that when he was

about 19 years old, Tutankhamun's life

was mysteriously cut short. Many have

viewed it as suspicious that as soon as

Tutankhamun was old enough to make

his own decisions and take on the role

of leader of his people-rather than

share it with Ay and Horemheb-he

was dead. After Tutankhamun's death,

his widow Ankhesenamun married Ay,

her own grandfather. A signet ring

bearing the names of Ay and

Ankhesenamun (and seemingly representing this union) has been found.

This marriage enabled Ay, who had no

royal blood, to inherit the throne.

Ankhesenamun disappears from the

records soon after the marriage, suggesting that she was murdered, possibly at the instigation of Ay. Shortly

after the death of her husband and just

before she vanished forever from history, she wrote one of the most startling letters ever recovered from the

ancient world.

The letter, sent by an Egyptian

"royal widow" has been dated to the

end of the 18th Dynasty, and was found

in the archives of the Hittite capital of Hattusa (modern Bogazkale) in Turkey. The document had been sent to

King Suppiluliumas I of the Hittites,

an emerging power in the Near East

at the time and an obvious danger to

Egypt. Part of the document states,

"My husband has died and I have no

son. They say about you that you have

many sons. You might give me one of

your sons to become my husband.

Never shall I pick out a servant of mine

and make him my husband! I am

afraid!" The Hittite king at first expressed suspicion at the motives of

Ankhesenamun, but after sending a

messenger to Egypt to investigate the

situation, who brought back a second

letter from the Egyptian queen, he

agreed to the marriage and sent his

son, the Prince Zannanza, to Egypt.

However, the prince only got as far as

the Egyptian border before he met his

death, probably murdered by an Egyptian faction who did not want a foreign king occupying the throne of

Egypt. This murder ultimately led to

war between the Egyptians and the

Hittites, and ended in defeat for Egypt

at Amqa, near Kadesh in western

Syria. Some have suggested that this

incredible letter was not written by

Ankhesenamun at all, but by her

mother Nefertiti, but this is unlikely

as Nefertiti's husband Akhenaten had

a successor, thus there would be no

need for a letter to a foreign king.

So what possible reason could

Ankhesenamun have had for instigating this treasonous correspondence,

which effectively amounts to her begging an enemy king to take over her

country? Tutankhamun's death (without leaving an heir) may have been at

the heart of the problem. One theory

is that the letters were written be

cause the Egyptians were wary of the

threat posed by the advancing Hittite

Empire, and believed that an alliance

with the Hittites by marriage would

preserve Egypt from conquest. The

queen may have planned to rule with

a Hittite king supported by the military might of the Hittite Empire, but

her plan was thwarted with the murder of Prince Zannanza. This brings us

to the fate of Tutankhamun himself.

Ever since Tutankhamun's body

was first unwrapped and examined by

Howard Carter's team in the 1920s,

there has been intense speculation as

to how and why the king died. X-ray

examinations of the skull, first in 1968

by a team from the University of

Liverpool, then in 1978 by researchers from the University of Michigan,

revealed a shard of bone in the skull

and evidence of hemorrhage at the

back of the head, possibly caused by a

deliberate blow to the skull. The evidence from the x-rays, taken together

with the suspicious circumstances surrounding King Tut's death, have

prompted many to conclude that the

boy pharaoh must have been murdered. But by whom?

The person most frequently put forward as being behind Tutankhamun's

possible murder is the man who had

most to gain by his death, the elderly

royal servant Ay. Ay reigned for a little

more than four years as pharaoh after

the demise of Tutankhamun, and

would seem to have had motive for

murder, though there is at present no

evidence that he had anything to do

with the death of the king. Other researchers believe a much younger

man, Horemheb, who succeeded Ay

around 1321 B.C., to become the last

pharaoh of ancient Egypt's 18th Dynasty, was responsible. Horemheb reigned for 27 years as pharaoh, during which time he brought about a

major reorganization of the country,

resulting in a much stronger and more

stable Egypt than had been seen for

many years. He was also determined

to completely return Egypt to its traditional religious beliefs, and he therefore set about obliterating all traces

of the Aten cult. It is thought that one

reason why Tutankhamun was omitted from the classical king lists of

Egypt is that Horemheb usurped most

of the boy pharaoh's work, including

monuments at Karnak and Luxor.

Could either of these two shadowy figures, or perhaps both, have plotted the

death of the boy pharaoh?

In January 2005, the first CAT

scans (a CAT scan is an x-ray technique

that produces a film representing a

detailed cross section of tissue structure) ever performed on an Egyptian

mummy were carried out on the 3,300

old skeleton of Tutankhamun. Surprisingly, the team of Egyptian researchers found no evidence at all of a blow

to the back of the boy's head, and no

other evidence of violence on the body.

The report stated that the fragment

of bone identified from previous skull

x-rays had probably become dislodged

during the embalming process. When

Tutankhamun was being mummified

his brain was removed and the skull

filled with large amounts of resin,

which has hardened over time. If the

sliver of bone had been the result of

an injury before death, it would not

still be loose in the skull. The dark

area shown at the back of the skull on

earlier x-rays, thought by many to indicate some kind of trauma, was explained by the scientists as the result

of the body being dismembered for

photographing after its initial discovery by Howard Carter. During this

process a rod had been inserted into

the back of the skull to prop it up. The

general conclusion of the researchers

was that Tutankhamun had been a

slightly built, but relatively healthy

young man standing roughly 5-feet 6inches tall. Using high-resolution photos of the CAT scans, three teams of

forensic artists from France, Egypt,

and the United States constructed

separate but similar models of the

king's face. The result not only bears a

striking resemblance to the famous

gold mask which covered the mummified face of Tutankhamun, but also to

a well-known image of the pharaoh as

a child where he was depicted as the

Sun God rising at dawn from a lotus

blossom. But how did the king die?

When examining Tutankhamun's

body the team found a fracture in the

thighbone of his left leg, previously

assumed by Howard Carter to have

been sustained during the embalming

process or as a result of damage to the

body after mummification. On reexamination, the scientists found that

this badly broken leg had occurred

only days before the death of

Tutankhamun and had probably led to

an attack of gangrene, which swiftly

brought about the king's death. At

present then, the evidence does not

support a murderous conspiracy by

Tutankhamun's close advisors Ay and

Horemheb, but more likely a broken

leg, perhaps sustained during a hunting accident, and not treated quickly

enough to prevent infection. The question of whether Ay or Horemheb could

have actively prevented the death of

the boy pharaoh from this injury is

another matter.