Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family (17 page)

Read Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family Online

Authors: Robert Kolker

1975

National Institute of Mental Health, Washington, D.C.

There were many days when Lynn DeLisi felt she was in the wrong place at the wrong time—that she didn’t belong in science, and that she’d been foolish to think she ever did. But the worst might have been the day she was told she might be driving her own children crazy.

This prognosis came her way from, of all people, a child psychiatrist at the National Institute of Mental Health, supposedly the vanguard of American psychiatric research. He said it in passing, in the middle of a lecture. DeLisi was one of a few women in the room, a first-year psychiatry resident at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. And she was the only mother—of two toddlers who, at that precise moment, were at home being cared for by a sitter. Like Yale’s Theodore Lidz, the family dynamics specialist, this psychiatrist seemed to believe in a connection between mental illness—specifically, schizophrenia—and the rise of the working woman. Mothers, the psychiatrist told the residents, ought to devote the first two years of their children’s lives to being with and caring for them at all times.

DeLisi couldn’t help but feel singled out. Of all the mothers in DeLisi’s neighborhood in suburban Annandale, Virginia, she was the only one who left her children with a nanny while she went to work, in Washington. Her husband worked, too, of course, but it fell on her to tailor the demands of her residency around parenthood: To avoid night calls, she had made a special arrangement to make up the hours by extending her residency longer than the normal allotted time.

While the other first-years remained silent, DeLisi started arguing, demanding some sort of proof. “Where is the evidence?” she said. “I want to see the data.”

But this psychiatrist had no data. He was citing not studies but Freud.

For weeks afterward, DeLisi could not stop thinking about how what he’d said with such certainty was informed not by experimentation and verification, but by anecdote and bias. What happened that day would color everything about DeLisi’s career in the years to come. In an era when schizophrenia treatment was torn between two approaches—psychotherapy or psychoactive medications—DeLisi was drawn to a third way: the search for a verifiable neurological cause of the disease.

SHE HAD WANTED

to be a doctor ever since she was a little girl in the suburbs of New Jersey. Her father, an electrical engineer, supported her dream and encouraged her; he would be the last man to do that for a while. She first thought of studying the brain and its relationship with mental illness at the University of Wisconsin, reading whatever she could about the neurological effects of hallucinogenic drugs. But her timing was not ideal. She graduated in 1966, when the Vietnam War was motivating many of her male classmates to apply to medical school to get deferments. Women who applied alongside those men were going in with an automatic disadvantage: Why would a medical school give a slot to a woman, when every man they turned down might be sent off to war?

Lynn struggled to find a work-around. She took a year off after college and found full-time work as a research assistant at Columbia University, and took graduate classes in biology at night at New York University. In the science library, she met the man she would marry, a graduate student named Charles DeLisi. Before their wedding, she enrolled in medical school at the only place that would take her: the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. After her first year, she applied to transfer to schools in New York, where Charles was still in graduate school. One interviewer asked if her family was more important to her than her career; another asked if she planned on using birth control. No one would take her.

Even her husband had expected her to quit medical school and switch over to a less demanding graduate program. But she stayed in the program with help from the dean—a woman who made a practice of championing young women in the profession—who arranged for DeLisi to take her second year of classes at NYU medical school. The next year, when DeLisi’s husband got a postdoc at Yale, they moved to New Haven; DeLisi commuted by train all the way back to classes at the Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia. When she got pregnant with her first child, her dean stepped in to help her again, arranging for her to take classes at Yale for her entire final year.

DeLisi graduated medical school in 1972. Once again, they moved for her husband’s work, this time to New Mexico, where Lynn started a general practice, treating poor migrant workers. She gave birth to their second child there, and when her husband had a job offer in Washington, she applied for residencies there. “I was interested in schizophrenia because it was a real disease of the brain,” she remembered. “It wasn’t, you know, just everyday anxiety. It was a real neurological disease.” Being close to NIMH, DeLisi thought, would put her alongside people who felt the same way.

It took time for her to find those people. While St. Elizabeths had wards full of schizophrenia patients, the study of schizophrenia as a physical ailment was not in fashion, at least among the supervisors of her residency program. One problem was practical: The patients never seemed to get better. Better to spend your career working on depression or eating or anxiety disorders or bipolar illness—something with even a glimmer of hope, that sometimes responded to the traditional cure of talk therapy.

Then there was the deeper problem—the same nature-nurture argument that had divided the field for decades. DeLisi’s program was really run by psychoanalysts, not medical psychiatrists, as she had hoped. During her residency, people like her who were interested in schizophrenia were allowed to take their third year at Chestnut Lodge. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann’s old command post was still in business, a few miles down the road in suburban Maryland, and the therapists there still considered childhood trauma to be one of the main influences in the development of serious mental illness. So did many of DeLisi’s teachers at St. Elizabeths.

DeLisi kept reading what she could find about the biology of schizophrenia, and she kept seeing the same name affiliated with NIMH: Richard Wyatt, a neuropsychiatrist who explored not therapy but the effects of mental illness on the brain itself. Wyatt’s lab was across town from the rest of the NIMH psychiatry program in the William A. White Building, a century-old red-brick structure on the St. Elizabeths campus with enough room to house patients for long-term study. In 1977, toward the end of her residency at St. Elizabeths, DeLisi went to see him about a fellowship. Wyatt was less than encouraging. He’d see what he could do, he told her, but he usually pulled his fellows straight from Harvard. What’s more, he said, no one was going to believe that a mother of two could handle the demands of the job.

This time, DeLisi wasn’t angry, just dejected. Even though she had arranged to extend the length of her residency, she had worked twice as hard so that she could finish on time anyway. She was every bit as good as any man, from Harvard or anywhere else. How many of the men in Wyatt’s lab had children? Did anyone ever ask that?

DeLisi’s mentors in her residency program couldn’t understand why she was so depressed. If she really wanted to study schizophrenia, they said, why not spend the final year of her residency at Chestnut Lodge?

Then came the surprise that would launch her career. Wyatt came back with an offer. If she wanted, she could complete her residency with a year in his lab. He’d be getting an extra employee for free, so this was hardly an imposition. If she did well enough, he said, she could continue there the following year as a fellow. No promises, but she could apply.

“I can get you in the back door, if you want,” Wyatt said.

ON THREE FLOORS

of the William A. White Building, Wyatt had separate labs for brain biochemistry, neuropathology, and electrophysiology; a sleep lab, and a lab where some of his staff collected postmortem human brains for study; and even an animal lab where others experimented with brain tissue transplantation. Wyatt’s primary interest was isolating biochemical factors affecting schizophrenia: blood platelet and lymphocyte markers and plasma proteins that might trigger psychosis or delusions. He had research wards with human subjects, each ward holding between ten and twelve patients, referred from all over the country to try experimental medications. Those patients were attended to by research fellows like DeLisi.

Most of Wyatt’s researchers were taking advantage of new CT scan technology to search for abnormalities in the brains of schizophrenia patients. These researchers already were finding enough physical evidence of schizophrenia in the human brain that many were ready to turn their back on the environment altogether as a cause of or contributor to the disease.

In 1979, Wyatt’s team published research showing that people with schizophrenia had more cerebrospinal fluid in their brain ventricles—the network of gaps in the tissue of the brain’s limbic system, where the amygdala and hippocampus are located. This was the part of the brain responsible for, among other things, maintaining a sense of awareness of your surroundings. The larger the ventricle size, the more resistant the patients seemed to be to neuroleptic drugs like Thorazine. Here was yet more proof that the illness was physical, not environmental. Or as one of the ventricle study coauthors, a psychiatrist at St. Elizabeths named E. Fuller Torrey, put it: “If bad parenting caused any of these diseases, we’d all be in big, big trouble.”

The only problem was that there was no way of telling whether enlarged ventricles were a cause or an effect—something patients were born with, or a condition they developed after they had the illness, maybe even as a side effect of their medication. That, DeLisi had thought, was where genetics would prove to be crucial. But the issue with studying the genetics of schizophrenia in 1979 was that most researchers considered such a thing to be little more than a fishing expedition. Schizophrenia was like Alzheimer’s or cancer—clearly the product of more than one gene, perhaps dozens working together—and therefore far too complex for genetic analysis, given how rudimentary the technology for such a search was at the time. This was why the Wyatt lab was focused on more available methods—MRIs, CT scans, and most recently PET scans. So for a time, DeLisi worked on that, too.

Her time with Wyatt was not without tension, and even conflict. DeLisi remembered feeling intense pressure to produce results that would lead to a prize-worthy study. More than once, she felt exploited, like the time she was asked to take the blame for a male colleague’s mistake because he was up for promotion. She said no; she had an aversion to going along with the boys, even when refusing did not serve her well politically with Wyatt. “It took two years before he talked to me like he talked to the men in the lab,” DeLisi remembered. “They would barge into his office and talk with him, and I could never get time with him.”

Finally, at around the same time that DeLisi successfully disproved a long-held hypothesis of Wyatt’s concerning the efficacy of a particular drug in treating schizophrenia, an abashed Wyatt remarked, in full view of the men, that she had surpassed them. “Which was nice of him to say,” DeLisi said. “But it didn’t make the men happy.”

EARLY ON IN

her time in Wyatt’s lab, DeLisi was approached by one of the grand old men of NIMH. David Rosenthal, still on hand as a research psychologist, had decided that it was time to do a follow-up study of the Genain quadruplets, to be published twenty years after the first one. The sisters were fifty now, all four of them still alive. This time they would be brought back for a battery of new biological tests, to see what else they had in common.

DeLisi was pleased by the chance to study the physical roots of the disease. She enjoyed being with the sisters, watching one of them say something and the next one parrot it a moment later, and then the next one, and the fourth one. She conducted CT scans, EEGs, and blood and urine studies. But for DeLisi, the real impact of spending time with four identical sisters with variations of the same illness was that she became more interested than ever in studying genetics.

The only schizophrenia researcher at NIMH who was looking closely at genetics was Elliot Gershon.

In 1978, Gershon had coauthored a paper that outlined the best way to verify a genetic marker for mental illness. His idea was to study families with more than one member with the disease. Gershon called these families “multiplex families.” The key, he said, was to focus not just on the sick people in the family, but everyone—ideally more than one generation. If researchers could somehow find a genetic abnormality that appeared in only the sick members of a family and not the well ones, then there it would be: the genetic smoking gun for schizophrenia.

DeLisi went to see Gershon and brought up the Genain sisters. Here was a family, the darlings of the NIMH schizophrenia wing, loaded to the brim with the illness, back in town and ready to be examined all over again. “What kind of studies would you do?” she asked.

Gershon’s answer brought her up short. “I don’t want to be part of this,” he said.

DeLisi asked why. She realized how off base the question was as soon as he answered.

“You’ve only got an N of one,” Gershon said—just one set of data, with no variation. “You’re not going to find anything really meaningful.”

Since all four sisters had the same genetic code, there would be nothing to compare or contrast. This was why Gershon saw no point in studying them. Families were the place to look, he said—but the right kind of families, with varying mixtures of the same genetic source ingredients. The more afflicted children, the better.

If DeLisi was up for tracking down families like those, Gershon said, maybe that would be something he could get behind.

DON

MIMI

DONALD

JIM

JOHN

MICHAEL

RICHARD

JOE

MARK

MATT

PETER

MARGARET

MARY

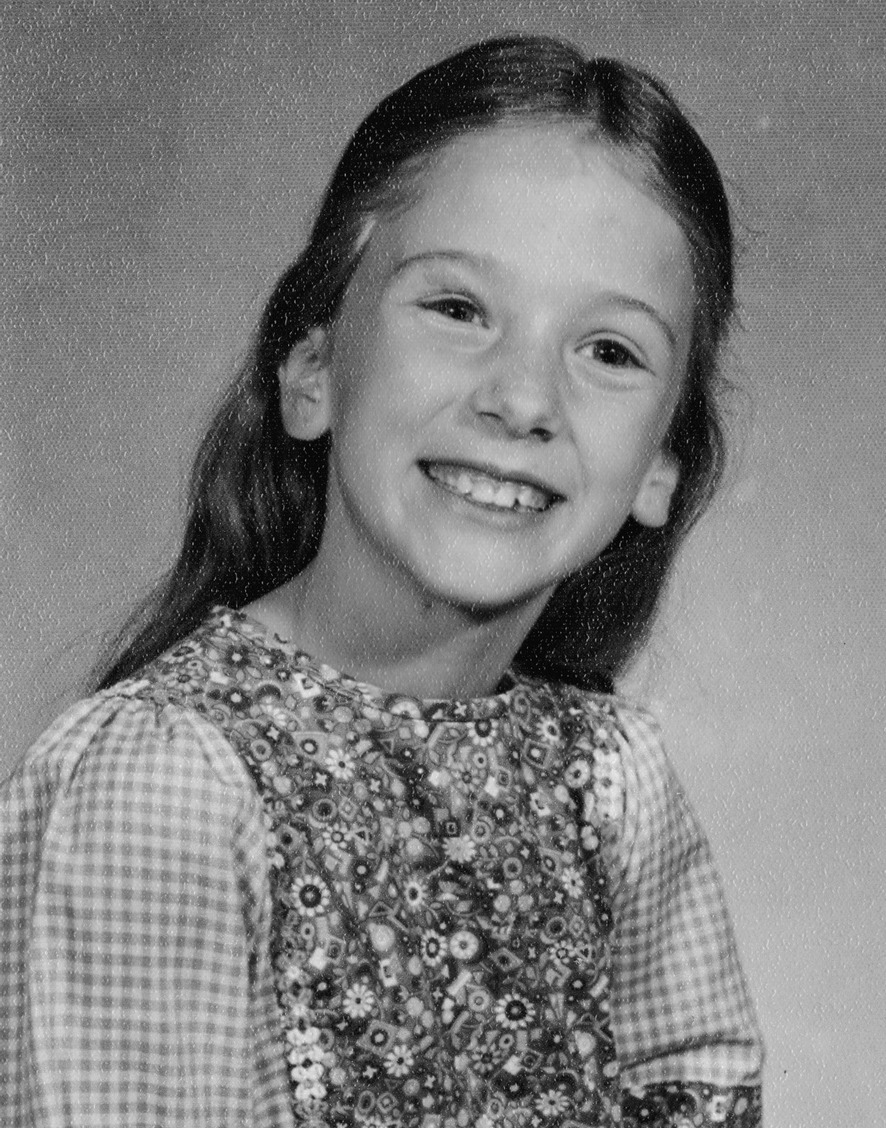

One of Mary Galvin’s earliest memories—from when she was about five years old, in 1970—was being in her bed late at night, trying to sleep, and hearing her oldest brother, Donald, home from the hospital, wailing in the hallway outside the door to her parents’ bedroom.

“I’m so scared,” he was saying. “I don’t know what’s happening.”

She remembered her parents trying to talk to him, telling him that everything would be all right—that they would find a doctor and figure out what was wrong.

And she remembered Donald running away from time to time—most often to Oregon, to find Jean—and her parents having to track him down, then send him plane or bus tickets.

And she remembered Donald at night again, this time terrified, yelling for everyone to get to safety. There were people in the house, he was saying, people trying to hurt them all.

She remembered believing him. Why would he lie?

MARY WAS DIFFERENT

from her big sister. Margaret was tender, empathic, and emotional; she would witness her family’s difficulties and internalize them, hardly able to bear the pain. Mary, meanwhile, may have been every bit as vulnerable, but she was also more practical, shrewd, and, perhaps by necessity now, independent. In first grade, she had been the only child to raise her hand for George McGovern and not Richard Nixon in her class’s mock presidential election. Later on, when she got caught with a cigarette at school, her mother asked what they ought to do about it, and Mary said, “Put up No Smoking signs.”

Once Margaret left home, taken away to Denver with Nancy and Sam Gary, Mary ricocheted between fury and silence. Her sister’s absence ate away at her. She could not understand why she was left behind. Her parents had tried to explain that she was not old enough for the private school Margaret attended there, but that meant nothing to Mary. It didn’t change how breathtakingly sudden it all had seemed to her.

In the fifth grade in 1976, Mary was all but alone—watching the fights among the brothers still at home. Peter was testing everyone around him, cycling in and out of the hospital and clashing with Matt, the last of the hockey boys still living at home. Donald had moved into Margaret’s room, next to Mary’s; the idea was to distance him from the other boys, who slept downstairs, but that just made him even less avoidable to Mary. When he wasn’t sleeping off his medications, Donald was pacing and gesticulating and talking to himself. Mary was embarrassed, snapping at him. When that didn’t work, she pleaded. And when that also didn’t work, she would cry, but not around anyone else. She spent hours in her bedroom, organizing and reorganizing her closet and her desk drawers, lost in thought, in an attempt to have some sense of control.

Out in the world, as she entered junior high school, Mary was all smiles—popular socially, spending more time at friends’ houses than at home. She knew that other children weren’t allowed to come to her house anymore. She didn’t want to be there, either. So she kept to a routine that would keep her away from Hidden Valley Road for as long as possible—from school to soccer in the afternoons and then evenings and Saturdays at the ballet studio at Colorado College; long visits to the Hefley family, who had a horse with a stall that could always use cleaning; anyplace but home.

Mary’s mother, after making herself so vulnerable to Nancy Gary and allowing the Gary family to take Margaret in, had tried to return to her old form, putting on a brave and cheerful face in public. With Mary, Mimi demonstrated the importance of not talking about it, of pretending it wasn’t happening—of not crying, not getting mad, not betraying the slightest emotion. The same sort of forced equanimity was expected of all the children. On drives from school to practice, or to the Chinook book shop in Colorado Springs, or to tea with the Crocketts or the Griffiths, Mimi offered Mary no explanation of why the brothers were the way they were, or what they could do to help. The most she would say was that the troubles of an eleven-year-old girl amounted to nothing compared to what her brothers were going through.

When Mary felt most helpless, she found a private place in the Woodmen Valley where she could hide, a few hundred yards from the house, on the other side of the hill in their backyard. She called it the Fairy Rocks. Mary would make believe that the Fairy Rocks were her home—pretending to cook dinner there, go to bed there, and wake up there the next morning, on her own and free.

MARY’S FATHER WOULD

take Mary with him to the community swimming pool at the Academy, where he was trying to manage a few laps to help him rehabilitate from his stroke. Don recognized people now, but his short-term memory was still compromised, and he seemed fated never to completely recover it. Where he used to speed-read his way through two or even three books a day, now he watched sports on the television, a device he had once not even wanted in the house. His falconry days were behind him. And returning to work was an impossibility. Sam Gary had thrown him a few consulting gigs in the oil industry, but Don wasn’t up to the task.

With the exception of Don’s military pension, there was no money coming in. The strain of caring for both Donald and Peter was impossible to deny. But whenever Don tried suggesting that Donald and Peter ought to live elsewhere, Mimi’s response would always be the same: “Where would they go?” This was a pointless pantomime by now: Mimi was in charge, they both knew that. But even if what her father said went nowhere, it meant something to Mary that he said it. At least he spoke up, making the case for the well children over the sick ones.

Mary would sit with her father as he watched golf on TV and look at him—his memory often working at half speed, his energy sapped—the only person willing to see her situation clearly, to sympathize, to take her side. Alone with her father, Mary would ask him why he was still a devoted Catholic—why, after everything that had happened, he still believed in God. This was not an abstract question to her; she still had to go to mass every Sunday, and she wanted to know what point there could possibly be to that now.

Don told her there had been many times in his life that he, too, had doubts. It was through his own reading and his own intellect, he said, that he found a way back to God.

He did not encourage Mary to do the same. He knew she was not one to be pushed.

SOMETIMES IT SEEMED

to Mary that her family had been cleft in two: not the crazy ones and the sane ones, but those still at home and those who got out. Among those still at home, her brother Matt was Mary’s soccer coach, and something of a guardian, her defender. Mary once wrote a school essay about him, anointing him the person she most looked up to. But in the spring of 1976, Matt graduated high school and left home, too. Then it was official: Just Mary and two of the sick ones, Peter and Donald. But Hidden Valley Road remained the primary way station for all the sick boys, their one reliable option when they were not welcome anywhere else—even Jim, when he was on the outs with Kathy.

It was all on Mary’s mother to choose the right treatments, to search for a solution, to protect them all. Mimi still deeply believed in a miracle. And, for a time, she thought she’d found one, courtesy of a pharmacologist out of Princeton, New Jersey, named Carl Pfeiffer. Pfeiffer’s journey through medicine was unorthodox and, at times, deeply strange. In the 1950s, he was

one of a handful of pharmacologists tapped by the CIA to conduct experiments with LSD on consenting prisoners. He went on to chair the pharmacology department at Emory University, but then left traditional academia in 1960 and started to publish a stream of papers, all devoid of standard double-blind testing and all based on the fervent belief that brain chemistry depended on a very particular balance of vitamins to keep a person mentally balanced—combinations of supplements that he was prepared to provide to anyone, for a price.

In 1973, Pfeiffer founded the Brain Bio Center, a private clinic that became his headquarters for several decades. Mimi, who had been reading everything she could get her hands on that suggested ways to improve one’s brain chemistry, learned about Pfeiffer just a few years after he’d set up shop. When she contacted him, the pharmacologist was more than eager to travel to Colorado to meet the mother of twelve whose sons were losing their minds. After his visit, he invited the Galvins to New Jersey for a complete work-up.

Everyone who was still at home packed up and traveled east to Princeton. Mary remembered someone checking her nails for white spots and being told she had a zinc deficiency, and her mother hanging on the pharmacologist’s every word, taking note of everything. Pfeiffer told everyone who came to the Brain Bio Center that what most people considered mental illness probably could be blamed on nutritional deficits. Even Marilyn Monroe and Judy Garland, Pfeiffer said, would be alive today if they had adjusted their blood nutrients. A psychiatric hospital was just, as he once wrote, a “

holding tank.” This must have been music to the ears of a mother who felt judged every moment, by doctors—and a husband—who suggested her boys would be better off in institutions.

Back home on Hidden Valley Road, Mimi made a ceramic mug by hand for each child. Each morning without fail, she filled the avocado-colored vessels with orange juice to help wash down Dr. Pfeiffer’s pills. On the way to school, Mary would get sick, her stomach on fire from the juice and vitamins. She started sticking the pills in her pocket on her way out the door, and chucking them into the woods as soon as she was out of sight.

IN MARCH

1976

—TWO

months after Margaret left home—a Colorado state highway patrolman noticed a dark-haired man walking east down Route 24 in the precise middle of the road, toeing the double yellow line and talking to himself as cars veered past him on either side. When the officer asked Donald to step to the side of the road, he refused. When he tried to arrest him, Donald started pushing and shoving. It took several officers plus some local firemen to subdue him. In the Colorado Springs jail, the police learned that he had been off his medication for the last several months.

The police transferred him to Pueblo, where by now Donald was rather well known. The doctors learned that he’d just come back home to Hidden Valley Road in January after some time away. He’d gone to Oregon again to find Jean, only to be told this time that she had joined the Peace Corps. He stayed in Oregon for a while, working on a shrimp boat. When he returned, Don and Mimi agreed to take him in, but only if he went to Pikes Peak Mental Health Center in Colorado Springs regularly for his medication. (“They are also involved with several other male children in the family,” according to a report from Pueblo.) Donald agreed, but then refused, becoming what the Pueblo doctors referred to as a management problem. “He and family both agree that he should not be living at home,” the report reads, “because of his age and his poor influence on other children in the family.”

He denies that he was having hallucinations but would turn his head frequently and look to the side as if he were listening to a voice. He has many religious preoccupations and talks about symbols constantly going through his mind. One of them he described was that of an infant in which the radiance of God was shining down upon. At several points during the interview, he became very tense and expressed hostile feelings such as wanting to knock my block off….

After a few days, Donald still seemed confused and restless and aggressive—or, as the staff put it, “assaultive, destructive, belligerent, suicidal, hyperactive, over-talkative, [and] grandiose.” He was written up for “masturbating openly” and “exposing self,” and for wandering into the women’s dorms and, once, the women’s shower. The doctors at Pueblo calmed Donald with Prolixin, but he still reported faithfully about the symbols and signs flashing through his mind.

Still, he was deemed stable enough to be released back home in April.

ON THE WEEKENDS,

Jim’s son, Jimmy—Mary’s nephew, though he was just a few years younger than she was—and Mary formed a little two-member day camp. Jim would tell Don and Mimi that he was taking them to church, and instead they would do something fun—go ice-skating, or to the park. Now more than ever, Mary’s Saturdays and Sundays with Jim and Kathy became something her parents counted on. “There would be a crisis,” she said, “and Mom would call Jim and Kathy to come and get me.”

Kathy became like Mary’s surrogate mother. That made Jim, in this scenario, the father.

Jim had been coming to her at night when she visited his house ever since Margaret left, when Mary was about ten. He penetrated her with his fingers and forced her into oral sex, and she tolerated him partly out of denial, and partly out of confusion. She remained passive based on the same calculus her sister had used: because she loved Kathy; because anything was better than being at home; because some part of her grew accustomed to not resisting, to interpreting the acts as affection.