Hieroglyphs (9 page)

Authors: Penelope Wilson

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #Ancient, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Art, #Ancient & Classical

34

The stages in attacking an Egyptian sentence are thus: (i)

explaining how the phrase is written: from left to right, with honorific transposition of the first sign, meaning ‘king’, because it is considered to be the most important of all the signs (ii) transliteration :

Htp di nsw

(putting into individual words, along the lines of pronunciation)

(iii) explaining how the phrase is built up (grammar and syntax): a relative clause

(iv) translation : ‘a gift which the king gives’

(v) understanding the phrase: one of the most common phrases on

Hi

Egyptian funerary monuments; it refers to the benefits and gifts

eroglyp

permitted by the king for the tomb owner or dead person

hic scri

(vi) understanding the phrase in the context of the whole sentence: what will follow is a list of the gods of the cemetery who also allow

pt an

gifts for the dead; then the list of gifts, usually along the lines of

d E

‘athousand bread, beer, oxen, fowl, cloth, ointment, alabaster, and

gyptian lan

all things good and pure’.

gua

Imitators

ge

Other ancient cultures tried to copy Egyptian hieroglyphs, in particular the kingdom of Meroe whose capital city of the same name was situated to the south of Egypt in the ancient kingdom of Nubia (modern Sudan). The kings of Meroe may have been descended from the Napatan kings of Dynasty 25 who had once ruled Egypt and regarded themselves almost as the guarantors of Egyptian kingship and as the protectors of the Egyptian gods with their impressive cult temple to Amun at Gebel Barkal. The Meroitic kings wrote their language in a form of pictorial script as well as in a more cursive script, like hieratic. It seems as if they borrowed the idea of the script from the Egyptians but, of course, they were writing a completely different language whose origins lay probably in ancient Nubian or one of the African languages spoken in 35

Eastern Africa in ancient times. Meroitic hieroglyphs form an

‘alphabet’ of twenty-four letters and, though the texts read from right to left, the animal and human signs face the other way.

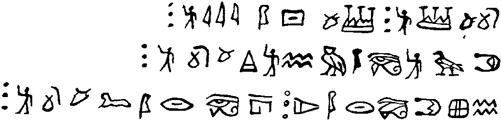

3. Meroitic hieroglyphs. This text from an offering table is now in Berlin

Museum, but originally from the Pyramids at Meroe. Eighteen of the

twenty-four signs can be seen here.

Transliteration

(reading right to left)

Translation

woshi : shore

O Isis and Osiris !

tekidje-mni qo wi

the blessed Takidje-amane,

phs

npt-djxet : t edjxelo wi

born of Napata-djakhete,

ogly

begotten of [Adjeckhetali]

Hier

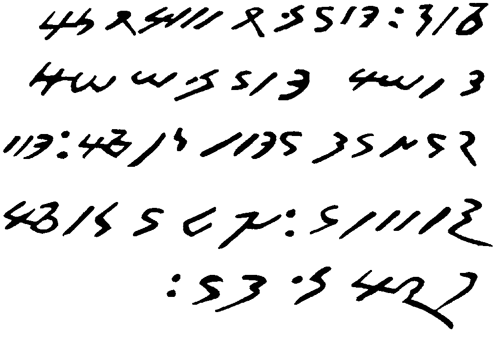

4. Meroitic cursive script. This text is from a stela from Amara and is

now in Khartoum Museum. Twenty of the twenty-four signs can be

seen here.

36

Transliteration (reading right to left)

Translation

woshi qetene yinele

O Isis, (epithet)

shore qeterre

O Osiris (epithet)

adjemeqo le wi : qo-

Adjemeqo, born of

-koye : djxelo

Qekaye, begotten of

mni-teme

Amani-teme

Few of the signs have the same appearance as the Egyptian hieroglyphs and none has the same value. In addition, Meroitic uses punctuation marks, a kind of colon between words, because there are no determinatives. The texts normally read from right to left and the cursive form is easy to recognize as the signs look like rows of numbers 2, 4, and 3, some of them with very long tails. Though

Hi

the basic value of the alphabet is understood, the Meroitic language

eroglyp

is still not totally deciphered. The basic meanings of some funerary

hic scri

texts can be understood, but the detailed meaning of long historical accounts is much less clear. As scholars continue to work on the

pt an

language there may be a breakthrough like the recent work done on

d E

Mayan. What is needed, however, is some kind of bilingual text,

gyptian lan

perhaps written in Meroitic and Demotic or Meroitic and Greek, so that the same two texts can be compared and understood. One of the last surviving sites where that might have been possible was the

gua

sacred hill site of Qasr Ibrim, where countless documents written in

ge

every language known in the Nile Valley have been found. The elusive bilingual text has not emerged, however, and the rising waters of Lake Nasser have percolated through the layers left there, probably causing the destruction of much of the remaining organic material.

37

Design of signs

Hieroglyphs had very specific purposes in Egypt. They were used for writing texts which were written for the gods, for an élite in the context of their relationship with the gods, and for the afterlife.

Though hieroglyphs were used to write a recognizable language of Egypt, it was an exalted mode of communication within a formal ritual setting and within an architectural framework defining spatial and temporal zones. Most people were unable to read hieroglyphs and only a specialist group were ever taught the principles of the pictorial signs. The guiding principles for writing in hieroglyphs come from Egyptian art and ceremonial ideology rather than language. The purpose of the scribes in writing the hieroglyphic texts was quite specific, rarefied, and intellectually élitist.

Individual signs are generally recognizable as something from the Egyptian world. We might not recognize them straight away because we do not carry milk vessels on strings with us, nor are twisted flax fibres in everyday use, and nor do we come across vultures, guinea fowl, or horned vipers every day. Learning hieroglyphic signs is not only a linguistic exercise but, perhaps unexpectedly, it brings with it all kinds of cultural baggage to enable us to understand Egyptian culture and daily life.

38

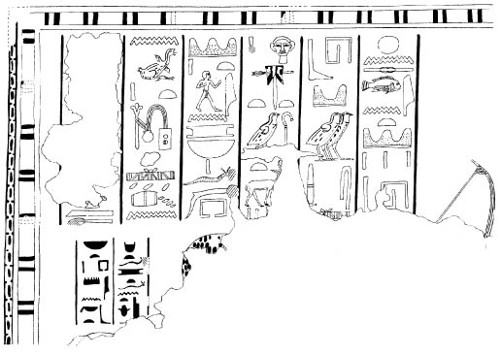

5. Hieroglyphs from the Tomb of Amenemhet, Thebes. Dating to

H

Dynasty 18, each hieroglyph was a work of art, with the individual

ieroglyp

feathers of the birds being painted.

hs an

d ar

Signs are made recognizable by design. The artists who created the

t

signs thought about the most recognizable form of the object which was being drawn. The human face can be seen both frontally, with its eyes and mouth, most apparent, or it can be seen in profile with the eye, nose, mouth, and chin being most prominent. The latter view was used as the hieroglyph for the Egyptian face. The principle of being able to recognize an object from its most obvious traits was used for every Egyptian image drawn in two dimensions.

Birds are shown from the side, except for the owl, which has its flat face towards the viewer so that the distinctive shape of its head and eyes are clear. Roads are shown as a double line with protrusions on either side. These are meant to represent bushes growing along the roadside. The hieroglyph represents the road from above as a bird’s eye view, with the bushes shown as stylized inverted triangles. This, too, is the rule for art – an object is drawn from a perspective that makes it most recognizable. A pool with trees around it is shown as seen from above with the trees flattened 39

against the ground. It may seem a strange perspective but is very logical.

Signs in context

The pictorial nature of writing allows it to blend with pictorial scenes on temple and tomb walls and the same principles governing the use of determinatives can also be applied at this larger scale, for example, in a temple wall register.

This scene from the Temple of Esna shows the king making an offering of two different types of sistra (musical rattles) to the goddesses Neith and Hathor. The figures are surrounded by lines of texts reading and proceeding in all directions. The texts concerned with the king read towards his face and are meant to emanate from him. The short vertical line directly in front of the king gives the title of the scene: ‘Playing the sistra for the Two Ladies’. Above his

phs

head two cartouches identify the king; in this case he is actually the

ogly

Roman emperor Titus. Behind him one vertical line of text reading

Hier

left to right gives more of his virtues and attributes (the other vertical line reads the other way and belongs to the next scene to the

6. Offering scene from the Temple of Esna.

40

right). All the other texts in this scene read from right to left and give the speeches, the names and titles, and the rewards of the goddesses. Again one vertical column of text at the left frames this scene. The bands of text divide, label, give the words, and most importantly stress that the correct procedures for this offering and the correct mythical context have been evoked. Though the detail may differ from temple to temple and from scene to scene, each ritual is one compact action. It functions individually but it also works collectively within the temple wall, within this particular element of the building, within the whole complex, and within the whole cosmic environment. Each hieroglyph has its part to play architecturally and creatively. The writing provides the context for the scenes and the detail, but the huge scene acts as a determinative in a giant piece of writing so that the texts can be read correctly. The scene also shows the correct gestures and offering stance to be used in the performance of each ritual.