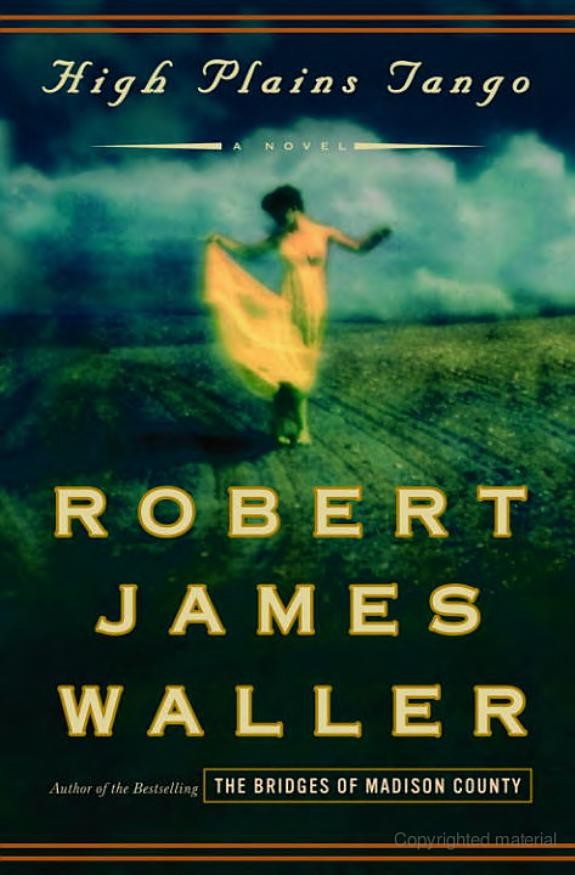

High Plains Tango

Authors: Robert James Waller

High Plains Tango

a novel

Robert James Waller

Shaye Areheart Books

NEW YORK

For my mother, Ruthie, who for years has lived in a quiet fog of Alzheimer’s disease, but who still smiles in recognition when she sees me and likes it when I hold her hand on winter afternoons.

“In some respects, George Armstrong Custer had a pleasant stroll by the river compared to what Carlisle McMillan went through, and afterward nobody placed any white markers in the thin, red soil of Yerkes County. Never been anything like it, not out here, at least . . . not anywhere else, probably. You name it, we had it: magic, war, Indians . . . so-called witches, for chrissake.”

“Mind if I quote you here and there, on the local stuff?” I asked.

“Keep buying the Wild Turkey, quote me all you want. Talk to Carlisle McMillan, too, get it straight from the hombre who went through it all.”

—

CONVERSATION

,

back booth in

SLEEPY’S STAGGER INN

Hell, we’re all just a bunch of dervishes, dancin’ around and chantin’ till the music ends. But you got to accept the tango runs forever. Susanna Benteen understood that. Not sure if anyone else did. She ain’t no witch, like people said. ’Least I don’t think so. She dances a sweet little tango, though, I’ll say that.

—Gabe O’Rourke,

ACCORDION PLAYER

Chapter One

N

OT EXACTLY A DARK AND STORMY NIGHT, BUT NONETHELESS:

a strange, far place in a strange, far time, distant buttes with low, wet clouds hanging across their rumpled white faces and long, straight highways running somewhere close to forever. In a settled land, the truly wild places are where nobody is looking anymore. This was a wild place.

Enigmatic sign pointing west.

Why did the eagle die? Did anyone remember? Some did, but they weren’t talking.

Red dirt road perpendicular to the highway, heading into the short grass and disappearing over a low rise a half mile out.

Other signs, every thirty miles or so, pointing to other roads hinting travel through invisible walls and into other times. If you had a vehicle with enough stamina, maybe turn off on one of them, just for the hell of it. We’ve all had a fleeting urge to do that.

That’s what Carlisle McMillan did. He was in no hurry, a traveler without design, a temporary drifter by his own choice. After turning his tan Chevy pickup off westbound pavement onto what the locals called Wolf Butte Road, he headed south past the Dead Eagle Canyon sign. After a while, he stopped his truck and got out, miles from the nearest little town.

Late August cool. Mist. Carlisle McMillan stood there for a few moments, boots becoming grass wet, sky water on his face and hands.

Easy wind came, went, came again. Silence. Cattails bending, yellow clover riffling as the wind chose. Like a film without a sound track—the silence—only deeper. More like a stone coffin at nightfall when the mourners have left and dirt has been shoveled over you.

The Cheyenne believed this was sacred ground. Sweet Medicine said it was so. The hawk sitting thirty fence posts south of Carlisle McMillan believed it. Anyone who happened on this place believed it. The smart money would come with food and water, perhaps a sleeping bag, in case an engine failed or a tire relented and the spare was empty. For nothing out here cared about you, that much was clear. Nothing cared whether you lived or died or paid your bills or danced on warm Pacific beaches and made love afterward. There was nothing except silence and wind, and they would be here long after your passing.

The Early Ones were buried here in mounds, giving the appearance of sea roll to the prairie. They shuffled across the old land bridges from Asia when the continents were connected in the high north. A century ago, others were buried in this place. Buried where they fell in the wars of Manifest Destiny, the great westward push. You could still find metal buttons from cavalry tunics if you scuffled around in the gravel and looked close. Other things, too, old knife handles, human shoulder bones splintered by lance and bullet, pipe stems. If you dug, you would find more, a lot more.

Six inches behind Carlisle McMillan’s left rear tire was a tunic button half buried in the mud. The winds of a hundred springs uncovered the button, rain washed it into a creek. The creek carried it onto a sandbar. A bird picked it up and flew toward a nest, dropping it when it turned out to be hard and tasteless. That particular button once fastened the coat of Trooper Jimmy C. Knowles, Seventh Cavalry, who rode behind a man they called Son of the Morning Star. Trooper Knowles thought well of his yellow-haired general and aspired to be a cut-and-paste copy of him. He would have ridden into hell with Son of the Morning Star. And he eventually did.

If you can get past the wind, listen beyond the silence, there are old sounds reverberating here. Distant bugles, squeak of cavalry leather, maybe the low thrum of time itself. And faint images of old riders from a long time ago, mounted on fine Appaloosas, breaking from the shadows of Dead Eagle Canyon, running hard across the roll of green prairie, and turning their ponies for autumn, steam coming from muzzles and mouths.

Sometimes you can even smell things farther out when the wind is just right. That’s what they said and still say. You have to lean back and flare your nostrils. Work at it. Then it will come to you. First the ordinary smells of big, open country and after that the faint whiff of old deceptions.

Not far from where Carlisle McMillan stood in light rain and looked out across the rise of nothing, the anthropologist fell to his death from one of the smaller buttes. There had been the sound of rushing air followed by the thump of something high in the middle of his back, causing him to stagger forward from where he was standing and launching him into downward flight. The first eighty feet or so, his fall had a certain purity in its form and velocity, almost graceful. Until he hit an outcropping. After that, it was a Raggedy-Ann tumble for the next six hundred feet. The only sound was his scream, and his only perception was that of the cliff face going by him in a blur of white sandstone. He smashed into rock and gravel at the bottom, neck twisted rearward in such a way that his chin could touch the bottom of his right shoulder blade. None of his colleagues on the plain below had seen it happen or heard his cry.

A pair of dark eyes had seen it, though—the man falling through cool sunlight, the thin and yellow sunlight that sweeps this land in middle spring—but nothing would be said. Nothing, not ever. It was the way of things. That was known long before the horse soldiers rode through here on their way to the Little Big Horn. That was known a long time ago.

Carlisle McMillan leaned on a fence post, looked west, stared at the distance. Great run of empty space, broken only by an occasional butte. The one a half mile to his right, 3,237 feet high, was called Wolf Butte. A woman was dancing there on the crest, but Carlisle couldn’t see her.

Bare feet on short grass, she moved. Far off, far down, she could just make out a figure standing beside a pickup truck. Twenty feet behind her, the Indian played a flute, his back resting against the gnarled trunk of a long-dead scrub pine.

A low-slung cloud moved onto the butte, the cold wetness of it touching the graceful arch of the woman’s back, touching the curve of her legs. It touched her face and the opal ring on her left middle finger and the silver bracelet around her right wrist, touched the silver falcon hanging from the chain around her neck. The Indian could not see her clearly anymore, only transient sightings through the cloud, a momentary view of leg or breast or the swing of long auburn hair as she turned. But still he played, knowing the cloud would pass, knowing she would come to him.

Far off and far down, Carlisle McMillan shifted his truck into reverse and backed onto the road, grinding into the mud a tunic button that once fastened the blue coat of Trooper Jimmy C. Knowles, Seventh Cavalry. When the cloud drifted away from the butte and the woman again could see what lay on the plain below her, the figure was gone, only the vague image of a pickup truck moving south.

The flute angled down to silence. She raised her arms through the mist to the sky, lowered them, and walked toward the Indian. He was old, but his body was hard like fence wire, and she settled onto him. The wind was light and cool and wet. Close to her, he could smell the sandalwood with which she had bathed that morning. The rain lifted for a moment, and over the Indian’s shoulder she watched the hawk flying toward a cliff, the same one from which her father had glimpsed the earth rising toward him.