History of the Second World War (12 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

The most astonishing of the opening series of coups was that at Narvik, for this far northern port was some 1,200 miles distant from the German naval bases. Two Norwegian coast-defence ships gallantly met the attacking German destroyers, but were quickly sunk. The shore defences made no attempt at resistance — more by incompetence than treachery. Next day a British destroyer flotilla steamed up the fiord and fought a mutually damaging action with the Germans, which on the 13th were finished off by the inroad of a stronger flotilla supported by the battleship

Warspite

. But by this time the German troops were established in and around Narvik.

Farther south, Trondheim was captured with ease after the German ships had run the gauntlet of the batteries dominating the fiord — a hazard that had dismayed Allied experts who had considered the problem. By securing Trondheim, the Germans had possessed themselves of the strategic key to central Norway, though the question remained whether their handful of troops there could be reinforced from the south.

At Bergen, the Germans suffered some damage from the Norwegian warships and batteries, but had little trouble once they were ashore.

In the approach to Oslo, however, the main invading force suffered a jolt. For the cruiser

Blucher,

carrying many of the military staff, was sunk by torpedoes from the Oscarborg fortress, and the attempt to force the passage was then given up until this fortress surrendered in the afternoon, after heavy air attack. Thus the capture of Norway’s capital devolved on the parachute troops who had landed on the Fornebu airfield; in the afternoon this token force staged a parade march into the city, and its bluff succeeded. But the delay at least enabled the King and Government to escape northward with a view to rallying resistance.

The capture of Copenhagen was timed to coincide with the intended arrival at Oslo. The Danish capital was easy of access from the sea, and shortly before 5 a.m. three small transports steamed into the harbour, covered by aircraft overhead. The Germans met no resistance on landing, and a battalion marched off to take the barracks by surprise. At the same time Denmark’s land frontier in Jutland was invaded, but after a brief exchange of fire resistance was abandoned. The occupation of Denmark went far to ensure the Germans’ control of a sheltered sea-corridor from their own ports to southern Norway, and also gave them advanced airfields from which they could support the troops there. While the Danes might have fought longer, their country was so vulnerable as to be hardly defensible against a powerful attack with modern weapons.

More prompt and resolute action might have recovered two of the key points in Norway which the Germans captured that morning. For at the time they landed, the main British fleet under Admiral Forbes was abreast of Bergen, and he thought of sending a force in to attack the German ships there. The Admiralty agreed, and suggested that a similar attack should be made at Trondheim. A little later, however, it was decided to postpone the Trondheim attack until the German battlecruisers were tracked down. Meanwhile a force of four cruisers and seven destroyers headed for Bergen, but when aircraft reported that two German cruisers were there, instead of one as earlier reported, the Admiralty was overcome with caution and cancelled the attack.

Once the Germans had established a lodgement in Norway, the best way of loosening it would have been to cut them off from supply and reinforcements. That could only be done by barring the passage of the Skaggerak, between Denmark and Norway. But it soon became clear that the Admiralty — from fear of German air attack — was not willing to send anything except submarines into the Skaggerak. Such caution revealed a realisation of the effect of airpower on seapower that the Admiralty had never shown before the war. But it reflected badly on Churchill’s judgement in seeking to spread the war to Scandinavia — for unless the Germans’ route of reinforcements could be effectively blocked nothing could stop them building up their strength in southern Norway, and they were bound to gain a growing advantage.

There still appeared to be a chance of preserving central Norway if the two long mountain defiles leading north from Oslo were firmly held, and the small German force at Trondheim was quickly overcome. To this aim British efforts were now bent. A week after the German coup, British landings were made north and south of Trondheim, at Namsos and Aandalsnes respectively, as a preliminary to the main and direct attack on Trondheim.

But a strange chain of mishaps followed the decision. General Hotblack, an able soldier with modern ideas, was appointed as the military commander; but after being briefed for his task he left the Admiralty about midnight to walk back to his club, and some hours later was found unconscious on the Duke of York’s Steps, having apparently had a sudden seizure. A successor was appointed next day and set off by air for Scapa but the plane suddenly dived into the ground when circling the airfield there.

Meantime a sudden change took place in the views of the Chiefs of Staff, and the Admiralty. On the 17th they had approved the plan but the next day swung round in opposition to it. The risks of the operation filled their minds. Although Churchill would have preferred to concentrate on Narvik, he was much upset at the way they had turned round.

The Chiefs of Staff now recommended, instead, that the landings at Namsos and Aandalsnes should be reinforced and developed into a pincer-move against Trondheim. On paper the chances looked good, for there were less than 2,000 German troops in that area, whereas the Allies landed 13,000. But the distance to be covered was long, the snow clogged movement, and the Allied troops proved much less capable than the Germans of overcoming the difficulties. The advance south from Namsos was upset by the threat to its rear produced by the landing of several small German parties near the top of the Trondheim fiord, supported by the one German destroyer in the area. The advance from Aandalsnes, instead of being able to swing north on Trondheim, soon turned into a defensive action against the German troops who were pushing from Oslo up the Gudbrand Valley and brushing aside the Norwegians. As the Allied troops were badly harried by air attack, and lacked air support themselves, the commanders on the spot recommended evacuation. The re-embarkation of the two forces was completed on May 1 and 2 — thus leaving the Germans in complete control of both southern and central Norway.

The Allies now concentrated on gaming Narvik — more for ‘face-saving’ purposes than from any continued hope of reaching the Swedish iron-mines. The original British landing in this area had been made on April 14, but the extreme caution of General Mackesy hindered any speedy attack on Narvik — despite the ardent promptings of Admiral Lord Cork and Orrery, who was put in charge of the combined force in this area. Even when the land forces had been built up to 20,000 troops, their progress was still slow. On the other side 2,000 Austrian Alpine troops reinforced by as many sailors from the German destroyers, and skilfully handled by General Died, made the most of the defensive advantages of the difficult country. Not until May 27 were they pushed out of Narvik town. By this time the German offensive in the West had bitten deep into France, which was on the verge of collapse. So on June 7 the Allied forces at Narvik were evacuated. The King and the Government left Norway at the same time.

Over the whole Scandinavian issue the Allied Governments had shown an excessive spirit of aggressiveness coupled with a deficient sense of time — with results that brought misery on the Norwegian people. By contrast Hitler had, for once, shown a prolonged reluctance to strike. But when he eventually made up his mind to forestall the Western powers he lost no more time — and his forces operated with a swiftness and audacity that amply offset the smallness of their numbers during the critical stage.

CHAPTER 7 - THE OVERRUNNING OF THE WEST

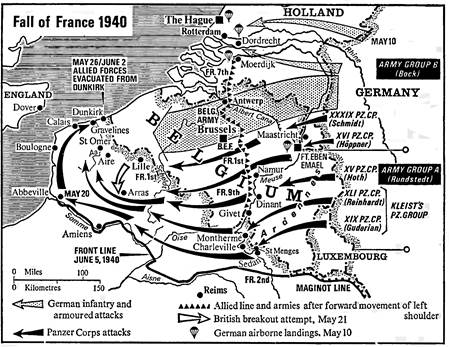

The course of the world in our time was changed, with far-reaching effects on the future of all peoples, when Hitler’s forces broke through the defence of the West on May 10, 1940. The decisive act of the world-shaking drama began on the 13th, when Guderian’s panzer corps crossed the Meuse at Sedan.

On May 10 also, Mr. Churchill, restless and dynamic, became Prime Minister of Great Britain in place of Mr. Chamberlain.

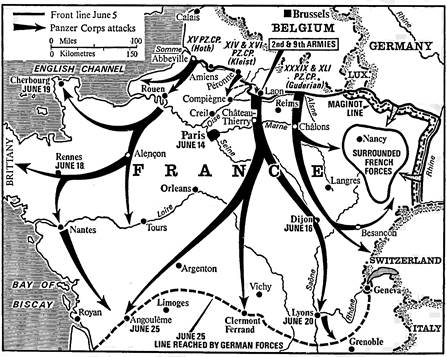

The narrow breach at Sedan was soon expanded into a vast gap. The German tanks, pouring through it, reached the Channel coast within a week, thus cutting off the Allied armies in Belgium. That disaster led on to the fall of France and the isolation of Britain. Although Britain managed to hold out behind her sea-ditch, rescue only came after a prolonged war had become a world-wide struggle. In the end Hitler was overthrown by the weight of America and Russia, but Europe was left exhausted and under the shadow of Communist domination.

After the catastrophe, the rupture of the French front was commonly viewed as inevitable, and Hitler’s attack as irresistible. But appearances were very different from reality — as has now become clear.

The heads of the German Army had little faith in the prospects of the offensive, which they had unwillingly launched on Hitler’s insistence. Hitler himself suffered a sudden loss of confidence at the crucial moment, and imposed a two days’ halt on the advance just as his spearhead pierced the French defence and had an open path in front of it. That would have been fatal to Hitler’s prospects of victory if the French had been capable of profiting from the breathing space.

But strangest of all, the man who led the spearhead — Guderian — suffered momentary removal from command as a result of his superiors’ anxiety to put a brake on his pace in exploiting the breakthrough he had made. Yet but for his ‘offence’ in driving so fast the invasion would probably have failed — and the whole course of world events would have been different from what it has been.

Far from having the overwhelming; superiority with which they were credited, Hitler’s armies were actually inferior in numbers to those opposing them. Although his tank drives proved decisive, he had fewer and less powerful tanks than his opponents possessed. Only in airpower, the most vital factor, had he a superiority.

Moreover, the issue was virtually decided by a small fraction of his forces before the bulk came into action. That decisive fraction comprised ten armoured divisions, one parachute division, and one air-portable division — besides the air force — out of a total of some 135 divisions which he had assembled.

The dazzling effect of what the new elements achieved has obscured not only their relatively small scale but the narrow margin by which success was gained. Their success could easily have been prevented but for the opportunities presented to them by the Allied blunders — blunders that were largely due to the prevalence of out-of-date ideas. Even as it was, with such help from the purblind leaders on the other side, the success of the invasion turned on a lucky series of long-odds chances — and on the readiness of one man, Guderian, to make the most of those which came his way.

The Battle of France is one of history’s most striking examples of the decisive effect of a new idea, carried out by a dynamic executant. Guderian has related how, before the war, his imagination was fired by the idea of deep strategic penetration by independent armoured forces — a long-range tank drive to cut the main arteries of the opposing army far back behind its front. A tank enthusiast, he grasped the potentialities of this idea, arising from that new current of military thought in Britain after the first World War, which the Royal Tank Corps had been the first to demonstrate in training practice. Most of the higher German generals were as dubious of the idea as the British and French authorities had been — regarding it as impracticable in war. But when war came Guderian seized the chance to carry it out despite the doubts of his superiors. The effect proved as decisive as other new ideas had been in earlier history — the use of the horse, the long spear, the phalanx, the flexible legion, the ‘oblique order’, the horse-archer, the longbow, the musket, the gun, the organisation of armies in separate and manoeuvrable divisions. Indeed, it proved more immediately decisive.