History of the Second World War (23 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

Cunningham’s forces then turned inland, into Southern Ethiopia, and by March 17 the 11th African Division occupied Jijiga, close to the provincial capital of Harar, after a 400 mile advance. That brought them close to the frontier of former British Somaliland, where a small force from Aden had re-landed on the 16th. By March 29, after some tougher resistance, Harar was occupied, and Cunningham’s forces then swung westward towards the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, 300 miles distant in the west centre of Ethiopia. Cunningham’s forces occupied it barely a week later, on April 6 — a month before the Emperor Haile Selassie returned to his capital, escorted by Wingate. The remarkably ready surrender of the Italians was hastened by reports of the atrocities committed by Ethiopian irregulars among Italian women.

In the north, however, the opposition was much stiffer, as it had been from the outset. Here General Frusci, who was in command, had about 17,000 well-equipped Italian troops in the front in the area of Eritrea, with over three divisions farther back. General Platt’s advance, starting in the third week of January, was carried out by the powerful 4th and 5th Indian Divisions. The Duke of Aosta had ordered the Italian forces in Eritrea to fall back before the British advance developed, and as a result the first serious stand was made at Keru, sixty miles east of Kassala and forty miles inside the Eritrean frontier.

Harder resistance was met by the two Indian columns in mountainous positions at Barentu and Agordat, respectively forty-five and seventy miles east of Keru. Fortunately the 4th Indian, under General Beresford-Peirse, reached the more distant objective first, and that eased the 5th Indian’s advance on Barentu.

Wavell then realised the possibility of extending his objective, to the conquest of Eritrea as a whole, and gave fresh orders to General Platt accordingly. But the capital, Asmara, was more than 100 miles beyond Agordat (and the port of Massawa further still), while almost midway between lay the mountainous position of Keren, one of the strongest defensive positions in East Africa, and the only gateway to Asmara and Massawa, the Italian naval base.

The first attempts to force a passage, starting early on February 3, were a failure, and suffered repeated repulses in the following days. The Italian commander on the spot, General Carnimeo, showed splendid fighting spirit and tactical skill. After more than a week of effort the attack was abandoned, and a long lull followed. Not until mid-March was the offensive resumed, when the 5th Indian Division was brought up and ready to join in. Once again the struggle was a prolonged one, and a series of Italian counter-attacks threw back the attackers, but at last on March 27 a squadron of heavily armoured ‘infantry’ tanks of the 4th R.T.R. broke through the block and pierced the Italian front — the same factor that in the hands of the 7th R.T.R. had been decisive in the successive North African battles from Sidi Barrani to Tobruk.

That finished the battle of Keren, after fifty-three days. General Frusci’s forces fell back southward into Ethiopia, and on April 1 the British occupied Asmara. Then they pushed on eastward to Massawa, fifty miles beyond, and produced its surrender, after a fight, on April 8. That ended the Eritrean campaign.

Meanwhile the remaining Italian forces, under the Duke of Aosta, had withdrawn southward into Ethiopia, planning a final stand in a mountain position at Amba Alagi, some eighty miles south of Asmara. He had only 7,000 troops left, with forty guns, and barely three months’ supplies. Moreover Italian morale was dwindling as a result of reports about the Ethiopian treatment of prisoners. So the Duke, though a gallant soldier, was more than willing to agree to surrender on ‘honourable terms’, which took place on May 19 — and brought the total of Italian prisoners to 230,000. There still remained isolated Italian forces under General Gazzera in the south-west of Ethiopia and in the north-west under General Nasi near Gondar, but these were rounded up in the summer and autumn respectively. That was the end of Mussolini’s short-lived African Empire.

PART IV - THE SPREAD - 1941

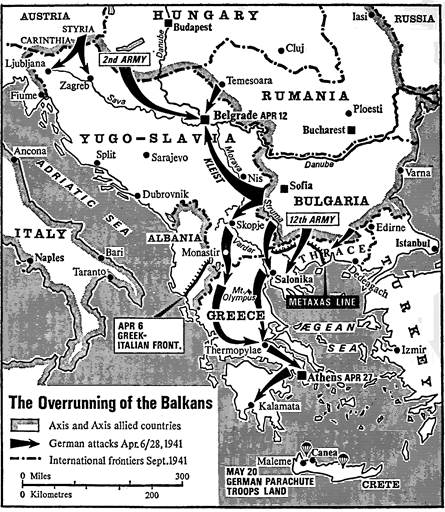

CHAPTER 11 - THE OVERRUNNING OF THE BALKANS AND CRETE

Some claim that the despatch of General Wilson’s force to Greece, though it ended in a hurried evacuation, was justified because it produced six weeks’ postponement of the invasion of Russia. This claim has been challenged, and the venture condemned as a political gamble, by a number of soldiers who were well acquainted with the Mediterranean situation — notably General de Guingand, later Montgomery’s Chief of Staff, who was on the joint Planning Staff in Cairo. They argue that a golden opportunity of exploiting the defeat of the Italians in Cyrenaica, and capturing Tripoli before German help arrived, was sacrificed in order to switch inadequate forces to Greece that had no real chance of saving her from a German invasion.

This latter view was confirmed by events. In three weeks, Greece was overrun and the British thrown out of the Balkans, while the reduced British force in Cyrenaica was also driven out by the German Afrika Korps, which had been enabled to land at Tripoli. These defeats meant a damaging loss of prestige and prospect for Britain, and only hastened the misery that was brought on the Greek people. Even if the Greek campaign was found to have retarded the invasion of Russia, that fact would not justify the British Government’s decision, for such an object was not in their minds at the time.

It is of historical interest, however, to discover whether the campaign actually had such an effect. The most definite piece of evidence in support of this lies in the fact that Hitler had originally ordered preparations for the attack on Russia to be completed by May 15, whereas at the end of March the tentative date was deferred about a month, and then fixed for June 22. Field-Marshal von Rundstedt said that the preparations of his Army Group had been hampered by the late arrival of the armoured divisions which had been employed in the Balkan campaign, and that this was the key-factor in the delay, in combination with the weather.

Field-Marshal von Kleist, who commanded the armoured forces under Rundstedt, was still more explicit. ‘It is true’, he said, ‘that the forces employed in the Balkans were not large compared with our total strength, but the proportion of tanks employed there was high. The bulk of the tanks that came under me for the offensive against the Russian front in southern Poland had taken part in the Balkan offensive, and needed overhaul, while their crews needed a rest. A large number of them had driven as far south as the Peloponnese, and had to be brought back all that way.’*

* Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill

, p. 251.

The views of Field-Marshals von Rundstedt and von Kleist were naturally conditioned by the extent to which the offensive on their front was dependent on the return of these armoured divisions. Other generals attached less importance to the effect of the Balkan campaign. They emphasised that the main role in the offensive against Russia was allotted to Field-Marshal von Bock’s Central Army Group in northern Poland, and that the chances of victory principally turned on its progress. A diminution of Rundstedt’s forces, for the secondary role of his Army Group, might not have affected the decisive issue, as the Russian forces could not be easily switched. It might even have checked Hitler’s inclination to switch his effort southward in the second stage of the invasion — an inclination that, as we shall see, had a fatally retarding effect on the prospects of reaching Moscow before the winter. The invasion, at a pinch, could have been launched without awaiting the reinforcement of Rundstedt’s Army Group by the arrival of the divisions from the Balkans. But, in the event, that argument for delay was reinforced by doubts whether the ground was dry enough to attempt an earlier start. General Halder’s view was that the weather conditions were not in fact suitable before the time when the invasion was actually launched.

The retrospective views of generals are not, however, a sure guide as to what might have been decided if there had been no Balkan complications. Once the tentative date had been postponed on that account the scales were weighted against any idea of striking before the extra divisions had returned from the quarter.

But it was not the Greek campaign that caused the postponement. Hitler had already reckoned with that commitment when the invasion of Greece was inserted in the 1941 programme, as a preliminary to the invasion of Russia. The decisive factor in the change of timing was the unexpected coup d’etat in Yugo-Slavia that took place on March 27, when General Simovich and his confederates overthrew the Government which had just previously committed Yugo-Slavia to a pact with the Axis. Hitler was so incensed by the upsetting news as to decide, that same day, to stage an overwhelming offensive against Yugo-Slavia. The additional forces, land and air, required for such a stroke involved a greater commitment than the Greek campaign alone would have done, and thus impelled Hitler to take his fuller and more fateful decision to put off the intended start of the attack on Russia.

It was the fear, not the fact, of a British landing that had prompted Hitler to move into Greece, and the outcome set his mind at rest. The landing did not even check the existing Government of Yugo-Slavia from making terms with Hitler. On the other hand, it may have encouraged Simovich in making his successful bid to overthrow the Government and defy Hitler — less successfully.

Still more illuminating was the summary of the operations in the Balkan campaign given by General von Greiffenberg, who was Chief of Staff of Field-Marshal List’s 12th Army which conducted the Balkan campaign.

Greiffenberg’s account emphasised, remembering the Allied lodgement at Salonika in 1915 which ultimately developed into a decisive strategic thrust in September 1918, that Hitler feared in 1941 that the British would again land in Salonika or on the southern coast of Thrace. This would place them in the rear of Army Group South when it advanced eastward into southern Russia. Hitler assumed that the British would try to advance into the Balkans as before — and recalled how at the end of World War I the Allied Balkan Army had materially contributed to the decision.

He therefore resolved, as a precautionary measure before beginning operations against Russia, to occupy the coast of Southern Thrace between Salonika and Dedeagach (Alexandropolis). The 12th Army (List) was earmarked for this operation, and included Kleist’s Panzer Group. The army assembled in Rumania, crossed the Danube into Bulgaria, and from there was to pierce the Metaxas Line — advancing with its right wing on Salonika and its left wing on Dedeagach. Once the coast was reached, the Bulgarians were to take over the main protection of the coast, where only a few German troops were to remain. The mass of the 12th Army, especially Kleist’s Panzer Group, was then to turn about and be sent northward via Rumania, to go into action on the southern sector of the Eastern Front. The original plan did not envisage the occupation of the main part of Greece.

When this plan was shown to King Boris of Bulgaria, he said that he did not trust Yugo-Slavia, which might threaten the right flank of the 12th Army. German representatives, however, assured King Boris that in view of the 1939 pact between Yugo-Slavia and Germany they anticipated no danger from that quarter. They had the impression that King Boris was not quite convinced.

He was proved right. When the 12th Army was about to begin operations from Bulgaria according to plan, the coup which led to the abdication of the Regent, Prince Paul, was suddenly launched in Belgrade, just before the movement of troops began.

It appeared that certain Belgrade circles disagreed with Prince Paul’s pro-German policy and wanted to side with the Western powers. Whether the Western powers or the U.S.S.R. backed the coup beforehand, we as soldiers cannot gauge. But at any rate it was not staged by Hitler! On the contrary it came as a very unpleasant surprise, and nearly upset the whole plan of operations of the 12th Army in Bulgaria.*

* Blumentritt in Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill

, p. 254.

For example, Kleist’s panzer divisions had to proceed immediately from Bulgaria north-westward against Belgrade. Another improvisation was an operation by the 2nd Army (Weichs), with quickly gathered formations based on Carinthia and Styria, southward into Yugo-Slavia. The flare-up in the Balkans compelled a postponement of the Russian campaign, from May to June. To this extent, therefore, the Belgrade coup materially influenced the start of Hitler’s attack on Russia.

But the weather also played an important part in 1941, and that was accidental. East of the Bug-San line in Poland, ground operations are very restricted until May, because most roads are muddy and the country generally is a morass. The many unregulated rivers cause widespread flooding. The farther one goes east the more pronounced do these disadvantages become, particularly in the boggy forest regions of the Rokitno (Pripet) and Beresina. Even in normal times movement is very restricted before mid-May, but 1941 was an exceptional year. The winter had lasted longer. As late as the beginning of June the Bug was over its banks for miles.