History of the Second World War (71 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

In such a situation, Montgomery was able to make the most of his ability for planning a well-woven defence, and the attack was shattered even more effectively than at Alam Haifa six months earlier. The advancing Germans were soon pinned down and whittled away by the British concentration of fire. Realising the futility of continuing, Rommel broke off his attack in the evening. But by that time he had lost more than forty tanks, although in men the casualties were only 645. The defenders’ losses were much slighter.

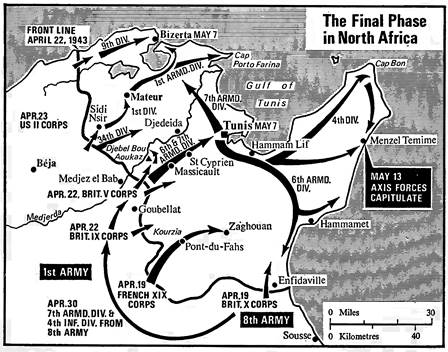

This repulse dispelled any reasonable hopes that the outnumbered and outweaponed Axis forces might be able to cripple one of the two Allied armies before they linked up and developed a combined pressure. Already the week before, Rommel had sent Kesselring a sober and sombre appreciation of the situation which embodied the view of his two army commanders, Arnim and Messe, as well as his own. In it he had emphasised that the Axis forces were holding a front of nearly 400 miles against much superior forces — twice as strong in men while six times as strong in tanks* — and were strung out perilously thin. He had urged that the front should be shortened to a ninety-mile arc covering Tunis and Bizerta, but said that this could only be held if supplies were increased to 140,000 tons a month, and had pointedly asked for enlightenment as to the higher command’s long-term plans for the Tunisian campaign. The reply he received, after several urgent reminders, simply said that the Fuhrer did not agree with his judgement of the situation. Attached to it was a table setting forth the number of formations on either side, irrespective of actual strength and equipment — the same false basis of comparison which the Allied commanders used, then and later, in rendering account of their successes.

* He estimated the Allies’ strength as 210,000 men, with 1,600 tanks, 850 guns and 1,100 anti-tank guns — an estimate which was under the mark. The Allies’ actual strength early in March was over 500,000 men, although barely half of them were fighting troops. The total of tanks was nearly 1800, with over 1,200 guns and over 1,500 anti-tank guns. The Axis fighting troops numbered 120,000, with barely 200 effective tanks.

After the failure at Medenine, Rommel came to the conclusion that it would be ‘plain suicide’ for the German-Italian forces to stay in Africa. So on March 9, taking his long deferred sick leave, he handed over command of the Army Group to Arnim, and flew to Europe in an effort to make his masters understand the situation. As it turned out, the result was merely to terminate his connection with the campaign in Africa.

On landing in Rome he saw Mussolini, who ‘seemed to lack any sense of reality in adversity, and spent the whole time searching for arguments to justify his views’. Then Rommel went on to see Hitler, who was impervious to Rommel’s arguments and made it plain that in his view ‘I had become a pessimist’. He barred Rommel from returning to Africa for the moment, and told him that he might thus get fit in time ‘to take command of operations against Casablanca’. In view of Casablanca’s remoteness on the Atlantic coast, it is evident that Hitler was still imagining that he could throw the Allies completely out of Africa — which showed his extreme state of delusion.

Meanwhile a converging Allied offensive was being mounted with greatly superior strength to capture the southern gateway into Tunisia, enable the Eighth Army to join up with the First, and pinch out Messe’s ‘First Italian Army’ — formerly Rommel’s ‘Panzerarmee Afrika’. (Bayerlein, although nominally no more than Messe’s German Chief of Staff, held direct and complete control of all the German components.)

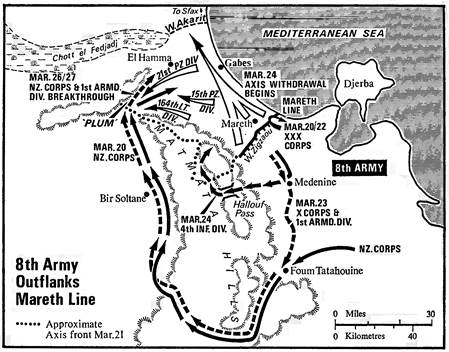

Following the heavy repulse of the German counterstroke at Medenine, Montgomery did not try to exploit this defensive success and the enemy’s shaken state by an immediate follow-up, but proceeded methodically to continue building up his forces and supplies for a deliberate attack on the Mareth Line. This was planned for delivery on March 20, two weeks after the Medenine battle.

To aid it, by leverage on the enemy’s back, an attack by the American 2nd Corps in southern Tunisia was launched three days earlier, on March 17. Its aims, prescribed by Anderson and endorsed by Alexander, were threefold — to draw off enemy resources that might be used to block Montgomery; to regain the forward airfields near Thelepte for use in aiding Montgomery’s advance; and to establish a forward supply centre near Gafsa, to help in provisioning him as he advanced. But the attacking force was not asked to cut off the enemy’s retreat by driving through to the coast-road. That limitation of its aims was inspired by doubts of the Americans’ capability for such a deep thrust — 160 miles to the sea from its starting points — and a desire to avoid exposing them to another German counterstroke such as they had suffered in February. But the restraint galled the aggressive ardour of Patton, who had been appointed to replace Fredendall as corps commander. The 2nd Corps now comprised four divisions and a strength of 88,000 men, which was about four times that of the Axis forces available to oppose them. Moreover in the target area there were estimated to be only 800 Germans and 7,850 Italians, the latter mainly with the Centauro Division near Gafsa.*

* Even this was an overestimate — the Centauro Division was only 5,000 strong before the February battles, and further depleted then.

The American attack started promisingly. On the 17th Allen’s 1st Infantry Division occupied Gafsa without a fight, the Italians withdrawing nearly twenty miles to a defile position east of El Guettar, astride the forking roads to the coastal towns of Gabes and Mahares. On the 20th Ward’s 1st Armored Division drove down from the Kasserine area onto the flank of the third route from Gafsa to the coast, and the next morning occupied Station de Sened, prior to advancing eastward through Maknassy to the pass beyond.

That day Alexander loosened the rein on Patton by telling him to prepare a strong armoured thrust to cut the coast-road, as a greater aid to Montgomery’s offensive against the Mareth Line, which had just been launched. But it was stultified by the stubborn defence of the pass and surrounding heights by the very small German detachment posted there, under Colonel Rudolf Lang. Successive attacks on the 23rd to capture the dominating Hill 322 were checked, although it was defended by only some eighty men composed of what had formerly been Rommel’s bodyguard. A renewed attack next day — by three battalions of infantry supported by four battalions of artillery and two companies of tanks — was again repulsed, although the defending force had only risen to 350 men. A fresh attempt was made on the 25th, led personally by Ward — on a peremptory telephone order from Patton, who insisted that the attack had to succeed. But it did not succeed and had to be abandoned in face of the enemy’s increased reinforcements. Patton had already complained that the division had ‘dawdled’, and Ward was subsequently relieved of command. But Patton was so attack-minded that he did not realise the inherent advantages of defence, even against much superior numbers — especially when conducted by highly skilled troops against inexperienced attackers.

Those advantages meanwhile had another demonstration in the El Guettar sector, and by troops who were comparatively inexperienced but particularly well trained — the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. Here Allen’s troops had broken into the Italian position on the 21st, and made some further progress next day, but on the 23rd were hit by a German counterstroke. This was delivered by the depleted 10th Panzer Division, the Army Group Afrika’s main reserve, which had been rushed up from the coast. (It comprised two tank and two infantry battalions with one motor-cycle and one artillery battalion.) The attackers overran the American forward positions but were then checked by a minefield, and then heavily hammered by Allen’s artillery and tank destroyers. That blunted the edge of the attack, and a renewal of it in the evening had no better success — as an American infantry report exultantly put it: ‘Our artillery crucified them with high explosive shells and they were falling like flies.’ Although the German loss in their second attack was not so heavy as here picturesquely reported, some forty tanks were knocked out by fire or disabled by mines during the day.

By drawing the enemy’s main armoured reserve into this costly counterstroke, the Americans’ limited thrust had brought compensation for its own failure at Maknassy. It had not only drawn off an important counterweight to Montgomery’s prospects, but drained away more of the enemy’s scanty tank strength. For their ultimate victory the Allies owed more to the enemy’s three unsuccessful counterstrokes, which followed the advantageous mid-February one at Faid, than they did to their own assaults. The possibility of gaining the ascendency came only after the enemy had overstrained and drained his own strength. Later the enemy might still have protracted the struggle but for the way he continued to use up his remaining strength in abortive retorts.

Montgomery’s attack on the Mareth Line was launched on the night of March 20. For it he had brought up both the 10th and the 30th Corps, with about 160,000 men, 610 tanks, and 1,410 guns. While Messe’s army comprised a nominal nine divisions compared with Montgomery’s six, it mustered less than 80,000 men, with 150 tanks (including those with the 10th Panzer Division near Gafsa) and 680 guns. Thus the attacker had a superiority of more than 2 to 1 in men and guns — as well as in aircraft — and 4 to 1 in tanks.

Moreover, the Mareth Line stretched for twenty-two miles, from the sea to the Matmata Hills, and beyond this range had an open desert flank. In the circumstances it would have been wiser for the relatively weak Axis forces to attempt merely a delaying defence of the Mareth Line, with mobile forces, and to make their stand on the Wadi Akarit position north of Gabes — a bottleneck barely fourteen miles wide between the sea and the saltmarshes, the ‘Chotts’. That was the course Rommel had advocated, and the position he had proposed, ever since the retreat from Alamein in November. When he saw Hitler on March 10, he had succeeded in getting Hitler to agree, and to instruct Kesselring that the non-mobile Italian divisions in the Mareth Line should be moved back to the Wadi Akarit to build a position there. But the Italian leaders preferred to hold on to the Mareth Line, and Kesselring, who shared their views, induced Hitler to cancel the new orders.

Montgomery’s original plan was codenamed ‘Pugilist Gallop’. Under it the main blow was a frontal one, by the three infantry divisions of Oliver Leese’s 30th Corps, intended to break through the defence near the sea and make a gap through which the armoured force of Brian Horrocks’s 10th Corps would drive to exploit success. At the same time, the provisionally formed New Zealand Corps under Bernard Freyberg made a wide outflanking march towards El Hamma (twenty-five miles inland from Gabes) to menace the enemy’s rear and pin down his reserves.

The frontal attack was a failure. Launched on a narrow sector near the coast, by one infantry brigade and a regiment of fifty infantry tanks, it made only a shallow dent in the enemy position — which was covered by the Wadi Zigzaou, 200 feet wide and 20 feet deep, and an anti-tank ditch beyond this. The soft bed of the wadi, and the mines laid there, hindered the advance of the tanks and supporting guns, while the infantry foothold in the enemy’s position beyond it became a concentrated target for enfilading fire. A reinforced renewal of the assault on the following night achieved some expansion of the bridgehead, and many of the Italian troops took the opportunity of surrendering when the British got in among them. But the arrival of the anti-tank guns was still delayed by the marshy ground they had to cross, and in the afternoon the forward infantry were overrun by a German counterattack* while still inadequately supported, and under cover of darkness the British fell back across the wadi. Thus by the night of the 22nd the frontal attack had not only failed to make an adequate breach, but abandoned its lodgement in the enemy defences.

* It was delivered by just under thirty tanks and two infantry battalions of the 15th Panzer Division.

Meanwhile the outflanking move had started well but then been held up. After a long approach march from the Eighth Army’s rear area, across a difficult stretch of desert, the New Zealand Corps had brought its 27,000 men and 200 tanks close to the hill-gap called ‘Plum’ — thirty miles west of Gabes and fifteen miles south-west of El Hamma — by the night of the 20th when the coastal assault opened. But after clearing the approaches it met a prolonged check at this hill-gap, where the Italian defenders were reinforced successively by the 21st Panzer Division from the reserve, and then by the four battalions of the 164th Light Afrika Division, which was brought back from the right of the Mareth Line.