History of the Second World War (82 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

Westphal also considered it was a mistake to land Montgomery’s Eighth Army on the toe of Italy, where it had to push up the whole length of the foot, while the greater opportunity on the exposed heel of Italy and along the Adriatic coast went begging:

The landing of the British Eighth Army should have taken place in full strength in the Taranto sector, where only one parachute division (with only three batteries of divisional artillery!) was stationed. Indeed, it would have been even better to have carried out the landing in the sector Pescara-Ancona. . . . No resistance to this landing could have been provided from the Rome sector, owing to our lack of available forces. Likewise no appreciable forces could have been brought down rapidly from the Po plain [in northern Italy].†

†

ibid.,

p. 365.

It would also have been impossible to switch Kesselring’s forces quickly from the west coast to the south-east coast if the main landing, by the Allied Fifth Army, had been made at Taranto instead of Salerno.

In sum, the Allies failed to profit either initially or subsequently from their greatest advantage, amphibious power — and its neglect became their greatest handicap. The evidence of Kesselring and Westphal supports, and in a wider way, the scathing conclusion which Churchill expressed in a telegram, from Carthage, to the British Chiefs of Staff on December 19:

the stagnation of the whole campaign on the Italian front is becoming scandalous. . . . The total neglect to provide amphibious action on the Adriatic side and the failure to strike any similar blow on the west have been disastrous.

None of the landing-craft in the Mediterranean have been put to the slightest use [for assault purposes] for three months. . . . There are few instances, even in this war, of such valuable forces being so completely wasted.*

* Churchill:

The Second World War,

Vol. V, p. 380.

What he did not see was that the doctrine of war on the Allied side was at fault — from following the cautious banker’s principle of ‘no advance without security’.

CHAPTER 28 - THE GERMAN EBB IN RUSSIA

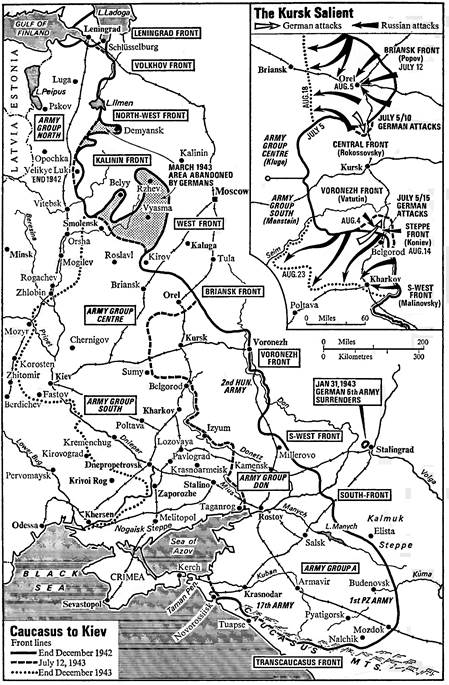

At the start of 1943 the German armies in the Caucasus looked likely to suffer the same fate as the Stalingrad armies. They were far deeper in the nose of the bag than the latter had been. Yet they had already been made to remain there for more than a month after the Stalingrad encirclement, while winter was deepening and danger extending. It was a grim outlook for the 1st Panzer Army and the 17th Army, composing ‘Army Group A’ — in command of which General Kleist had succeeded Field-Marshal List.

In the first week of January, the precarious situation of ‘Army Group A’ was emphasised by the development of multiple enveloping threats. The most direct was where its head stuck into the Caucasus mountains. The Russians struck first at its left cheek near Mozdok, and then at its right cheek near Nalchik, regaining both places. More dangerous was a simultaneous Russian move across the Kalmuk Steppes 200 miles behind its left flank, at the joint between it and ‘Army Group Don’. Capturing Elista, the Russians drove down past that end of Lake Manych towards Armavir — through which ran Kleist’s communications with Rostov. Most dangerous of all was a sudden surge southward down the Don line, from the Stalingrad direction, towards Rostov itself. One of the Russian spearheads came within fifty miles of that bottleneck.

This alarming news reached Kleist on the same day that he received an emphatic order from Hitler that he was not to withdraw his front in any circumstances. At that moment his 1st Panzer Army stood nearly 400 miles

east

of Rostov. The next day he received a fresh order — to retreat from the Caucasus, bringing all his equipment away with him. That requirement added to the handicap of distance in a race with time.

To leave the Rostov routes clear for the 1st Panzer Army, the 17th Army was ordered to withdraw westwards along the Kuban River towards the Taman peninsula, whence it might if necessary be transported back across the Kerch Straits into the Crimea. That withdrawal was not a long step, and the Russian forces recently besieged in the coastal strip around Tuapse were not strong enough to exert a dangerous pressure on the retreating 17th Army.

By contrast, the retreat of the 1st Panzer Army was beset with perils, both direct and indirect. The most dangerous phase was from January 15 until February 1, by which time the bulk of that army had reached Rostov. Even so, the continuation of its line of retreat, though not so narrowly constricted, was menaced by a series of Russian thrusts ranging over a further two hundred miles.

On January 10 General Rokossovsky had launched a concentric assault on the encircled German forces at Stalingrad, following the rejection of a Russian ultimatum to surrender. Paulus’s troops were so enfeebled by hunger, cold, disease, depression, and shortage of ammunition that they were in no state to offer strong or prolonged resistance. Still less were they capable of breaking out of the ring. Thus the Russians were able to spare part of the investing forces to reinforce the southward drive to cut off the Germans’ Caucasus forces, and more were released as the ring was contracted.

As this final act at Stalingrad began, Kleist’s forces, having withdrawn from the nose of their Caucasus salient, were standing on the Kuma River, between Pyatigorsk and Budenovsk. Ten days later the Russian thrust south from Elista reached a point more than a hundred miles in rear of the Kuma line. But by then Kleist’s retreating columns were nearing Armavir, and thus passing the immediate point of danger.

Nevertheless, farther back an acute danger was developing from the more powerful Russian drive down both sides of the Don towards Rostov. On the east side the Russians were now close to the Manych River and the rail junction of Salsk. On the west side they had reached the Donetz not far from the point where it entered the lower Don. Kleist’s rearguards had still three times as far to go as the Russians before they could reach Rostov. Moreover, Manstein’s exhausted forces, striving to cover the flank of Kleist’s escape-corridor, were now so hard-pressed that they seemed on the verge of cracking under the strain.

The retreating forces won the race, however, and managed to slip out of the trap. Ten days later Kleist’s rearguards were close to Rostov, and their would-be interrupters had been baffled. Luckily for the Germans the desolate snow-covered country had limited even the Russians’ capacity to push on beyond their distant railheads fast enough and in force enough to close the trap. But its jaws had only been held open by a narrow margin. Manstein’s forces had clung on so long to exposed positions that their own chances of withdrawal were jeopardised, and some of Kleist’s divisions had to be rushed back to help in extricating them, as well as reinforcing them.

The German forces from the Caucasus safely crossed the Don at Rostov just as the Stalingrad forces collapsed. Paulus himself and a large section of them surrendered on January 31. The last remaining fragment surrendered on February 2. In all, 92,000 had been taken prisoner since the start of the assault three weeks earlier, while the total loss had been nearly three times that figure. Among those who surrendered were twenty-four generals. Although the German generals on the Eastern Front had been provided with little tubes of poison in case they fell into Russian hands, few seem to have used these until after the failure of the ‘Generals’ Plot’ to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944, when they began to do so rather than risk delivery into the hands of the Gestapo. But ‘Stalingrad’ henceforth worked like a subtle poison in the minds of the German commanders everywhere, undermining their confidence in the strategy which they were called on to execute. Morally even more than materially, the disaster to that army at Stalingrad had an effect from which the German Army never recovered.

Yet there was justification for Hitler’s consoling declaration that the sacrifice of the army at Stalingrad had given the Supreme Command time for, and the possibility of, countermeasures on which depended the fate of the whole Eastern Front. If the army at Stalingrad had surrendered any time during the first seven weeks after its encirclement, a much greater disaster might have overtaken the other German armies. For Manstein’s scanty forces could not possibly have withstood the Russian flood that would have poured down the Don to Rostov, and the forces in the Caucasus would have been cut off. Their fate might also have been sealed if the army at Stalingrad had succeeded in breaking out of the trap and retreating westward. Moreover, although its resistance during the last fortnight of January was not strong enough to prevent the Russians pushing down towards Rostov in great strength, it still detained a proportion of their strength sufficient to make a vital difference to the chances of the Caucasus forces reaching Rostov in time to slip through the bottleneck.

Even with this help the retreat from the Caucasus was achieved by the narrowest of margins. In terms of time, space, force, and weather conditions it was an astonishing performance — for which Kleist was made a field-marshal. While the skill and tenacity with which it was conducted deserves due recognition, its greatest significance lies in the proof it provided of the extraordinary resisting power inherent in modern defence so long as commanders and troops keep cool heads and stout hearts.

Further proof came in the weeks that followed. For after the retreating armies had passed safely through the Rostov bottleneck they had still to deal with dangers that were developing far back on their line of retreat. In the middle of January General Vatutin’s left wing had resumed its push southward from the central Don to the Donetz behind Rostov. Besides producing the collapse of Millerovo, after that tough obstacle had been by-passed, the Donetz itself was crossed at and east of Kamensk.

In the same week two fresh Russian offensives had been launched. One was far away in the Leningrad sector. This broke the seventeen months’ encirclement of that great city, lifting the pressure of the siege. Although it did not go far enough to wipe out the German salient that had projected to Lake Ladoga, across the rear of the city, it cut a hole through to Schlusselburg along the lake shore — and that strategic tracheotomy created a windpipe through which the garrison and population could breathe more freely.

The other fresh offensive menaced the Germans’ breathing space in the south. It was launched on 12 January by General Golikov’s armies from the western stretch of the Don below Voronezh, and broke through the front of the 2nd Army and the 2nd Hungarian Army. Within a week it had penetrated a hundred miles — half way from the Don to Kharkov. General Vatutin’s right wing delivered a converging thrust eastward down the corridor between the Don and the Donetz.

In the last week of January the offensive was extended afresh. While attention was focused on the south-westerly drive towards Kharkov, the Russians struck westward from Voronezh on a broad front, upset the local withdrawal that the Germans were making there, and turned this into a widespread reflux. In barely three days the Russians had advanced nearly half way to Kursk — the springboard from which the enemy had launched his summer offensive.

During the first week of February they threw their right shoulder forward, and drove a wedge deep across the railway and road between Kursk and Orel. Then they drove another wedge across the line between Kursk and Belgorod. Having thus outflanked Kursk on both sides they captured the city on February 7 by a sudden bound forward. In the same way the second wedge they had driven was used as a means to produce the collapse of Belgorod two days later. This gain, in turn, became a threat to the northern flank of Kharkov.

Meanwhile, the apparently direct advance on Kharkov had developed a more south-westerly bias — towards the Sea of Azov and the line of retreat from Rostov. On the 5th Vatutin’s forces captured Izyum — where the Germans had created their decisive flanking leverage in the spring — and exploited their crossing of the Donetz to form a leverage the other way round. After driving a wedge across the railway south of the Donetz, they spread westwards and captured the important rail junction of Lozovaya on the 11th.

These fresh gains undermined the situation of Kharkov itself, which fell into Golikov’s hands on the 16th. That was a triumph, yet the more immediate danger to the German situation as a whole came from the Russians’ continued southward push from the Donetz towards the Sea of Azov. Four days earlier, a mobile force had reached Krasnoarmeisk, on the main line from Rostov back to Dnepropetrovsk. Such a development threatened to cut off the retreat of the armies that had just escaped from the Caucasus trap.

The alternating pattern and rhythm of the Russian offensive had become even more marked than during its earlier stage. It is easy to appreciate what a strain was thus placed on the Germans’ resisting power, and their already overstretched resources — taking account of the wideness of the front which they had to cover with a shrinking margin of reserves. The progressive and variable way in which the Russians had played on that weakness provided an illuminating demonstration of the Russians’ improved technique and the way they had learnt to exploit their new superiority. Examining the process by which they had captured such an important succession of key places, it can be seen that in each case the capture — even when it followed upon an advance in the immediate neighbourhood — was the sequel to an indirect move which virtually made the place untenable, or at best crippled its strategic value. The effect of that series of indirect leverages can be clearly traced in the pattern of operations. The Red Army Command might be likened to a pianist running his hands up and down the keyboard.