Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (19 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

7.36Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

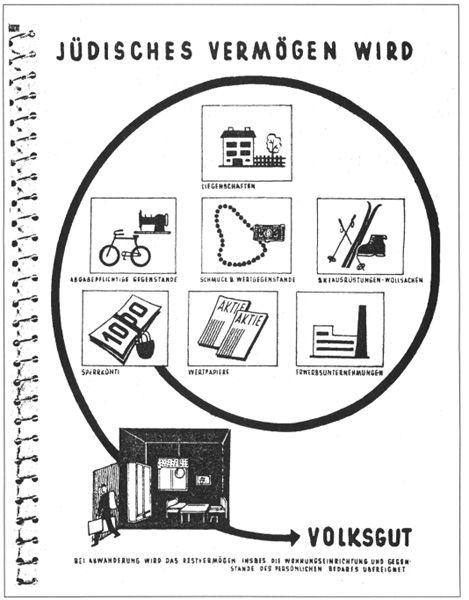

Immediately after the initial wave of deportations, the head of the Cologne Finance Department ordered not only apartments and houses “but also household effects, especially textiles and furnishings, put into the deserving hands of victims of bombing raids, newly married couples, widows of fallen soldiers, etc.”

78

The head of the Westphalian Finance Department, who was located in heavily damaged Münster, also instructed his subordinates to ensure “that goods, especially linens and household furnishings, get to the right recipients—air raid victims, newly married couples, war widows, etc.”

79

At the express wish of Joseph Goebbels in his capacity as gauleiter of Berlin, district authorities in the German capital hoarded the belongings of deportees “for the purpose of supplying [our] ethnic comrades who suffered damage in bombing raids and as a reserve supply for possible future damage.”

80

78

The head of the Westphalian Finance Department, who was located in heavily damaged Münster, also instructed his subordinates to ensure “that goods, especially linens and household furnishings, get to the right recipients—air raid victims, newly married couples, war widows, etc.”

79

At the express wish of Joseph Goebbels in his capacity as gauleiter of Berlin, district authorities in the German capital hoarded the belongings of deportees “for the purpose of supplying [our] ethnic comrades who suffered damage in bombing raids and as a reserve supply for possible future damage.”

80

In early November 1941, when the Reich finance minister ordered the immediate sale of “Jewish assets” at the best available prices, his first prioritwas raising quick, easy cash for the Reich. He barely mentioned the destruction wrought by aerial warfare. By summer 1942 that had changed. From then on, “sufferers from bombing damage” were to be taken into account “in the disposal of the household effects” of deported Jews. Mayors were instructed to store confiscated belongings for future eventualities and to transfer the artificially low revenues of the sales to Berlin.

81

A variety of institutions competed with air raid sufferers for a share of the loot. For the modest sum of 1,850.50 reichsmarks, the Cologne city orphanage bought furniture from the Jewish Children’s Home; an old-age home, a hospital, the music academy, and the public library also got in on the act. Private citizens, depending on their class and therefore needs, could acquire volumes of Rilke’s poetry and sheet music to Mozart’s

Requiem

, or simply a pair of shoes, a school knapsack, or a set of bed linens.

82

81

A variety of institutions competed with air raid sufferers for a share of the loot. For the modest sum of 1,850.50 reichsmarks, the Cologne city orphanage bought furniture from the Jewish Children’s Home; an old-age home, a hospital, the music academy, and the public library also got in on the act. Private citizens, depending on their class and therefore needs, could acquire volumes of Rilke’s poetry and sheet music to Mozart’s

Requiem

, or simply a pair of shoes, a school knapsack, or a set of bed linens.

82

In December 1941, Nazi Party ideologue Alfred Rosenberg suggested confiscating the household effects of those Jews “who had fled or were in the process of fleeing” Paris and “all other occupied territories of Western Europe.” His sights were set on the personal belongings of Jews in France, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg. Confiscated furnishings were earmarked for German civil servants recently assigned to the eastern territories, whose “terrible living conditions” might thus be raised to the levels of comfort to which they were accustomed. Rosenberg advanced the idea of stealing Jews’ possessions in his dual function as the Reich minister for the occupied eastern territory and as the head of his own task force (Einsatzstab). The latter body was responsible for the theft of artworks in occupied Europe and routinely inspected the homes of Jews who had fled or been taken into custody “for the purpose of securing Jewish cultural property.”

Hitler signed off on Rosenberg’s idea several weeks later, with the caveat, presumably after consultation with the finance minister, that “confiscated objects were to become property of the Reich.” He also redirected the new confiscations. Because military transports took precedence, making it impossible to transfer seized belongings to German civil servants in the occupied Soviet Union, they were to be used “for the Reich” itself.

83

He envisioned a program of streamlined emergency assistance for German air raid victims. With the RAF stepping up aerial bombardments, seizures from deported German Jews alone would soon no longer suffice to cover the supplies needed.

83

He envisioned a program of streamlined emergency assistance for German air raid victims. With the RAF stepping up aerial bombardments, seizures from deported German Jews alone would soon no longer suffice to cover the supplies needed.

On January 14,1942, Rosenberg repeated his order to appropriate “in their entirety the household effects of Jews who have fled or are in the process of fleeing the occupied western territories.” To coordinate these seizures, he appointed the head of the German Red Cross, Kurt von Behr, who had previously been responsible for the theft of artworks. Von Behr later boasted that he himself—and not Rosenberg—had devised the “furniture operation,” which the Führer then approved.

84

Regardless of who first thought of stealing the household effects of refugees and deportees, there is no doubt that it was the Army High Command that issued the orders that paved the way. The Finance Ministry later determined that Hitler had merely “approved the message,” while the Army High Command “ordered it,” belying the still common notion that the German military had nothing to do with the Final Solution.

85

84

Regardless of who first thought of stealing the household effects of refugees and deportees, there is no doubt that it was the Army High Command that issued the orders that paved the way. The Finance Ministry later determined that Hitler had merely “approved the message,” while the Army High Command “ordered it,” belying the still common notion that the German military had nothing to do with the Final Solution.

85

Von Behr was soon presiding over the distribution of scarce commodities such as bed, table, and personal linens, porcelain, dishes, silverware, and household appliances. In the first phase of the operation, replacement household effects were directed to the bomb-damaged cities of Oberhausen, Bottrop, Recklinghausen, Münster, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Osnabrück, Hamburg, Lübeck, and Karlsruhe.

86

The operation was an immediate success, and von Behr was quickly freed from his other duties as “director of the Louvre task force,” where he served as Rosenberg’s chief looter of art. Thereafter, the Red Cross official dedicated all his energies to the “securing of Jewish household effects for the victims of air raids.”

87

86

The operation was an immediate success, and von Behr was quickly freed from his other duties as “director of the Louvre task force,” where he served as Rosenberg’s chief looter of art. Thereafter, the Red Cross official dedicated all his energies to the “securing of Jewish household effects for the victims of air raids.”

87

Germany’s ambassador to France advised his superiors not to inform the French government in advance about the confiscation of furnishings, since there was ultimately “no formal legal justification for the operation.” In a pinch, he added, one could argue for its “immediate historical necessity” as part of a common European battle Germany was waging against Bolshevism.

88

Some of those who participated in the operation may have used that pretense—that the furniture was being requisitioned for the joint German-French struggle against Soviet Communism—to disguise an act of simple theft that violated international law. Göring, however, was not bothered by such scruples. He took it as a matter of course that “household effects from the occupied territories should be placed at the disposal of air raid victims in the Reich.”

89

The Vichy government repeatedly demanded “compensation” for “home furnishings transferred to Russia,” including the effects of dispossessed Jews, which constituted part of “the French people’s collective assets.”

90

Vichy collaborators, however, were asking not for those effects to be returned but rather for their value to written off the occupation costs France was forced to pay.

88

Some of those who participated in the operation may have used that pretense—that the furniture was being requisitioned for the joint German-French struggle against Soviet Communism—to disguise an act of simple theft that violated international law. Göring, however, was not bothered by such scruples. He took it as a matter of course that “household effects from the occupied territories should be placed at the disposal of air raid victims in the Reich.”

89

The Vichy government repeatedly demanded “compensation” for “home furnishings transferred to Russia,” including the effects of dispossessed Jews, which constituted part of “the French people’s collective assets.”

90

Vichy collaborators, however, were asking not for those effects to be returned but rather for their value to written off the occupation costs France was forced to pay.

On November 17, 1943, Rosenberg reported personally to Hitler on the progress of the furniture operation. He noted: “With the Führer’s permission, [goods from] some 250,000 Jewish households have been confiscated. Of those, 47,000 have been delivered to the Reich and been placed by regional leaders at the disposal of those who suffered losses from bombing raids. Transport to the Reich is continuing, as are further confiscations in France.”

91

Within two months, Hitler’s willing and unwilling assistants—French transport companies and Jewish forced laborers—had shipped property from a further 10,000 households to Germany. (The forced laborers received the truly “minimal wage of five francs a day”—the equivalent today of $3.)

92

By the end of 1943, the theft included almost a million cubic meters of furniture, for whose transport more than 24,000 freight cars had been required. (Precise figures for the substantial amount of furniture transported by sea and river are not available.)

91

Within two months, Hitler’s willing and unwilling assistants—French transport companies and Jewish forced laborers—had shipped property from a further 10,000 households to Germany. (The forced laborers received the truly “minimal wage of five francs a day”—the equivalent today of $3.)

92

By the end of 1943, the theft included almost a million cubic meters of furniture, for whose transport more than 24,000 freight cars had been required. (Precise figures for the substantial amount of furniture transported by sea and river are not available.)

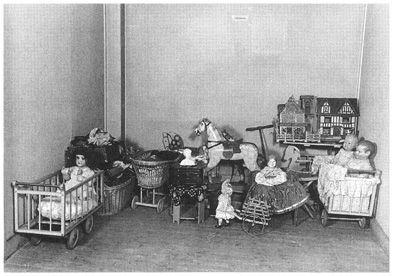

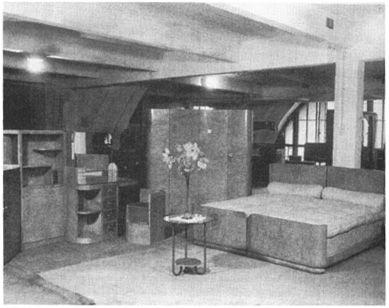

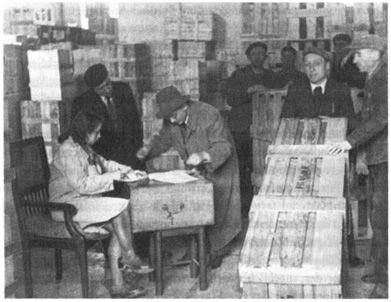

Lightbulbs, children’s toys, bed and table linens, furniture, and household effects of all varieties are sorted through by Jewish forced laborers in Paris, then collected and prepared for transport to German cities bombed by the Allies. Paris, September 1943. (Bundesarchiv)

A dispute between the president of the Cologne Finance Department and his subordinate in the Finance Office in nearby Trier illustrates how smoothly the supply was flowing. Citing the continual bombardment of his city, the Cologne official demanded the transfer of furniture confiscated from deported Jews in Trier, Cologne’s relatively untouched provincial neighbor. His subordinate in Trier countered by saying the furniture was needed locally. After a period of four weeks, the Cologne official relented “because of the plentiful deliveries of household goods from abroad.”

93

(Even the transport costs were paid by others.) On May 30-31, 1942, the Allies launched what became known as the “thousand bomber attack” against Cologne. In his final report, the city gauleiter, Josef Grohé, declared somewhat vaguely: “With the help of military commanders in Belgium and northern France, it has been possible to transport large quantities of rationing-exempt textiles to Cologne. Appropriate measures have been taken with respect to providing the populace with furniture, household effects, and basic commodities.”

94

93

(Even the transport costs were paid by others.) On May 30-31, 1942, the Allies launched what became known as the “thousand bomber attack” against Cologne. In his final report, the city gauleiter, Josef Grohé, declared somewhat vaguely: “With the help of military commanders in Belgium and northern France, it has been possible to transport large quantities of rationing-exempt textiles to Cologne. Appropriate measures have been taken with respect to providing the populace with furniture, household effects, and basic commodities.”

94

In Belgium, von Behr and his subordinates confiscated the furnishings of 3,868 apartments owned or rented by Jews. Some of the booty went directly to the military, but the vast majority was sent to air raid survivors in Düsseldorf, Mainz, Holzminden, Oberhausen, Cologne, Münster, Wanne-Eickel, Königs Wusterhausen, Berlin, Recklinghausen, Gelsenkirchen, Gladbeck, Bottrop, Aachen, Bremen, Hamburg, Soltau, Uelzen, Winsen, and Celle. A total of twenty-eight vehicles full of furniture arrived in Aachen within three weeks during the summer of 1943. “Household goods and linens formerly owned by foreign Jews” were distributed to bombed-out German families and “gratefully received.” Also among the recipients were large families and wounded veterans, whose claims had long been acknowledged but theretofore unaddressed.

A government document from the summer of 1944 records that the cities receiving the largest shipments were Karlsruhe with 481 freight cars full of furniture taken from West European Jews, Mannheim with 508, Berlin with 528, Düsseldorf with 488, Essen with 518, Duisburg with 693, Oberhausen with 605, Hamburg with 2,699, Cologne with 1,269, Rostock with 703, Oldenburg with 884, Osnabrück with 1,269, Wilhelmshaven with 441, Delmenhorst with 3,260, Münster with 523, Bochum with 555, and Kleve with 310. At the same time the contents of 8,191 freight cars were directed to central depots, where furniture could be promptly transferred to bombed-out civilians. The contents of 1,576 of these freight cars went to families of rail workers living in company settlements, who were, because of their proximity to train stations, particularly at risk of bombardment. The SS claimed the contents of some 500 others.

95

95

Other books

The Detention Club by David Yoo

The Breakup by Brenda Grate

Accidentally Flirting with the CEO (Whirlwind Romance Series) by Richards, Shadonna

The Toynbee Convector by Ray Bradbury

Hitched by Karpov Kinrade

Air Ticket by Susan Barrie

The Zero Hour by Joseph Finder

HeroRevealed by Anna Alexander

Bound With Pearls by Bristol, Sidney

The Islanders by Pascal Garnier