Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (28 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

8.23Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

THE SHEER amount of key agricultural products the Wehrmacht diverted from the Soviet Union can partly—but only partly—be gauged by the figures the Reich Office of Statistics kept for the years 1941–42 and 1942–43.

63

63

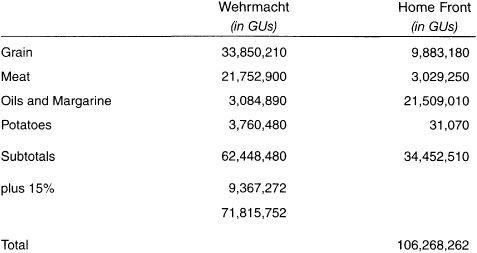

Table 3: Soviet Food Transfers to the Reich, 1941–43, by Recipient

Recent statisticians have pointed out that these numbers do not include foods “directly produced or seized by the troops themselves.” The amounts, writes one researcher, “while lower, would still be large: for grain alone, for example, hundreds of thousands of tons. One should also keep in mind the maintenance requirements of Reich citizens who worked in Eastern Europe (civil servants, employees of companies involved in the East).” Furthermore, the official statistics do not include the personal shopping sprees millions of German soldiers went on during the two years in question. Even the Reich’s own statisticians concluded that the amounts of unrecorded “food extractions” were “quite considerable, even if less than the recorded amounts.” One can thus add a conservative estimate of 15 percent to the official Wehrmacht statistics to reflect the minimum amount of food consumption. In reality, that percentage was probably much higher.

Comparing these totals with statistics for the amounts of agricultural goods produced within Germany shows that the exploitation of Soviet territory increased the Reich’s grain supplies by 10 percent, its stocks of oils and margarine by more than 60 percent, and meat by around 12 percent.

64

It’s easy to grasp how theft on this scale led to mass starvation in the Soviet Union.

64

It’s easy to grasp how theft on this scale led to mass starvation in the Soviet Union.

A minimum allowance of 2.5 grain units (GU) per year is needed to keep a person alive. One GU is the equivalent of 100 kilos of grain and varying amounts of other foods. In the early 1940s, Backe’s academic advisers, the renowned agronomists Emil Woermann and Georg Blum, developed a conversion table used by the Reich Food Ministry.* Based on the amount of energy that could be derived from various types of nutrition, it served as the scientific foundation for calculating wartime food rations. (Today, the system is used to distribute humanitarian aid efficiently in areas of catastrophe.)

The GU scale illustrates the devastating impact of German seizures of agricultural products in Eastern Europe. Again, the figures come from the Reich Office of Statistics.

Table 4: Nutritional Value of Soviet Food Transfers to the Reich, 1941–43, by Recipient

Since table 4 covers two years, if the total is divided by five (2.5×2), the resulting figure represents the number of people whose nutritional basis for survival was removed. Before the war, the Soviet Union produced 101 percent of the food its population needed. That percentage would have declined, owing to wartime disruptions in production, even without German plundering.

65

The seizure of food for the Reich meant that approximately 21.2 million Soviet citizens saw the nutritional basis for their survival eliminated.

65

The seizure of food for the Reich meant that approximately 21.2 million Soviet citizens saw the nutritional basis for their survival eliminated.

The reality of Soviet suffering was almost certainly worse than the calculations indicate. A statement from a conference of German state secretaries held on May 21,1941, asserted: “The war can be continued only if in the third year of the conflict the entire Wehrmacht is fed on Russian supplies. It will undoubtedly entail starvation for many millions of people, when we extract what we need from their land.”

66

66

A letter written from the Ukrainian city of Kirovgrad in the summer of 1942 gives a clear sense of the spirit with which Germans went about plundering food in Eastern Europe. The author was an employee of a firm whose task it was “to register and secure all production facilities, agricultural as well as industrial, and to secure the southern part of the Eastern Front, with all its wealth of food and amenities.” After opening with an anti-Semitic remark (“Jews? Forget about them!”), the author characterizes his primary job as relieving “the home front as much as possible from the need to send supplies.” Anything left over that “the Wehrmacht couldn’t find a use for” was to be sent back to Germany. “Huge amounts of wheat, sunflower seeds, sunflower oil, and eggs are being transported for distribution to the Reich. If, as my wife wrote me, the few weeks of food production should see the successful delivery of sunflower oil, I can say with pride that I was directly involved in this operation.”

67

67

Food extracted from occupied countries was primarily allocated to German soldiers, who then sent a not inconsiderable portion back home. Beginning in 1942, an increasing amount of food was also shipped directly back to the Reich for workers engaged in hard physical labor, pregnant women, and Aryan senior citizens and infants. But supplies also went to ordinary German consumers—those who possessed standard food ration cards that didn’t allow for any special allocations. They, too, were to be kept happy and content.

The level of the rations and the relative equity with which food was distributed strengthened Germans’ faith in their political leadership. It was not until February 1945 that complaints were heard from women with children in Berlin that they were not “regularly receiving whole milk.”

68

Decades after 1945, German women still recalled: “During the war we didn’t go hungry. Back then everything worked. It was only after the war that things turned bad.”

68

Decades after 1945, German women still recalled: “During the war we didn’t go hungry. Back then everything worked. It was only after the war that things turned bad.”

Then there were cities like Leningrad, where in January 1942 between 3,500 and 4,000 people died every day. One survivor recalls: “It was nearly impossible to get hold of a coffin. Hundreds of bodies were simply left lying around, wrapped only in cloth, in cemeteries or the surrounding areas. The authorities buried the bodies in mass graves, which were dug by civil defense troops with the help of explosives. We didn’t have the strength to dig normal graves in the frozen ground.”

69

69

Part III

THE DISPOSSESSION OF THE JEWS

CHAPTER 7

Larceny as a State Principle

Inflation and Aryanization

In the standard historical view, German businessmen and bank directors were the ones who profited most from the Aryanization of Jewish-owned property. This widespread but mistaken impression has been strengthened by studies of firms’ activities during the Nazi years that a number of European states and large corporations commissioned professional historians to undertake in the 1990s. More nuanced academic treatments have shown that Nazi functionaries at all levels of the bureaucracy also benefited from the Aryanization process. The most recent research has focused on ordinary Germans, as well as Poles, Czechs, and Hungarians, who were often paid for services performed for the Reich in money or goods seized from Jews. Yet studies that focus exclusively on individual, private profiteers fail to get to the heart of the question: what ultimately happened to the property of Jews who were first dispossessed and then murdered?

The answer requires an understanding of how Germans financed World War II. Almost everywhere in Europe where Aryanization took place, the liquidation of Jewish assets was carried out by state or occupation authorities. Corruption, embezzlement, and self-enrichment accompanied this process, as it does with every revolutionary redistribution of assets. But as a rule, private citizens who acquired expropriated stocks, real estate, furniture, or clothing paid for them—even if the prices they paid were lower than the assets’ inflationary wartime market value. Moreover, without exception, Jewish-owned assets were first nationalized, then privatized. In the lingo of German financial administrators, Jewish property “fell” to the state.

Although much of what was confiscated was sold off at bargain prices, state treasuries earned significant revenues from the transactions. The expropriation and sale of Jewish assets in 1938 was not just a onetime emergency measure the Reich took to close gaps in state finances. The procedure served as a model for use in the countries and regions Germany conquered during World War II. Aryanization was essentially a gigantic, trans-European trafficking operation in stolen goods. It may have taken different forms in different countries, but the ultimate destination of the revenues generated was always the German war chest. These funds enabled the Reich to defray its main financial burdens. Exact figures on the magnitude of the theft are ficult to come by, however, since in many places the nationalization of Jewish assets coincided with the blanket dispossession of other groups of people.

THE NAZI-CONTROLLED General Government of Poland provides a vivid illustration of how expropriation worked. In 1939, Poland had a Jewish population of around 2 million. Shortly after invading the country, the German occupiers froze all bank accounts, safety deposit boxes, and security accounts registered in Jewish names. By decree, the owners of these assets were required to keep them all at one bank. Deposits of more than 2,000 zlotys—around $12,000 today—had to be paid into accounts from which the owners could withdraw no more than 250 zlotys a week to cover their costs of living. In cases where state-appointed trustees were already overseeing Jewish assets, they were required to follow the new rules.

1

In November 1939, the Trust Office of the General Government of Poland was founded. It was responsible for securing what had been Polish national assets, confiscating property that had become ownerless because of the war, and dispossessing Jews and “enemies” of the Reich.

2

The revenues were ostensibly to be directed, as the government’s financial division in Cracow never tired of stressing, to the “main account of the General Government” itself.

3

1

In November 1939, the Trust Office of the General Government of Poland was founded. It was responsible for securing what had been Polish national assets, confiscating property that had become ownerless because of the war, and dispossessing Jews and “enemies” of the Reich.

2

The revenues were ostensibly to be directed, as the government’s financial division in Cracow never tired of stressing, to the “main account of the General Government” itself.

3

The Trust Office took over some 3,600 businesses, most of which had been owned by Jews. Of those businesses, around a thousand were considered “major.” Jewish real estate assets in Warsaw included some 50,000 pieces of property with a value of at least 2 billion zlotys. They were to be sold off “as soon as humanly possible.” To facilitate the sale of massive amounts of personal property, the trust administrator, Oskar Friedrich Plodeck, formed the Trust Utilization Company (Treuhand-Verwertungs GmbH). This corporation sold off the household effects and clothing of Jews who had been deported to ghettos and of Polish Christians who had fled the country or been declared enemies of the state. By the time the company, which was organized as a private firm, finished its work in 1942, Plodeck could report that it had taken in property worth some 50 million zlotys.

4

4

Strict rules prevented local officials from pocketing significant amounts of this money, even if occasional abuses did occur. As a rule, the surplus revenues from “trustee”-managed property, capital, and businesses were diligently transferred to the main account of the General Government. Initially, trustees issued meager support payments to the previous owners of these assets, and an official of the Trust Office even proclaimed that “the right to own property remains for the time being unchanged.” It was only after Jews had been deported and murdered that their belongings, which had been managed in the interest of the state and which had, in effect, already been confiscated, legally became “abandoned assets” and “property of the General Government.”

5

5

But the governments of countries conquered by Germany were required to pay the proceeds of such windfalls back to the Reich in the form of occupation fees. According to figures from the Reich Finance Ministry in October 1941, the occupation costs for Belgium represented 125 percent of that country’s regular state revenues. In the Netherlands the figure was 131 percent; in Serbia, 100 percent.

6

A Reichsbank study that used a different methodology estimated the cost for the first year of he occupation of France at 211 percent of regular state revenues. For Belgium, it arrived at a total of 200 percent, and for Holland 180 percent, of normal state income. Norway’s costs were calculated at 242 percent.

7

And by late 1942, “Wehrmacht requisitions of approximately 240 million Norwegian crowns” represented “339 percent of tax revenues and 95 percent of the gross national product.”

8

6

A Reichsbank study that used a different methodology estimated the cost for the first year of he occupation of France at 211 percent of regular state revenues. For Belgium, it arrived at a total of 200 percent, and for Holland 180 percent, of normal state income. Norway’s costs were calculated at 242 percent.

7

And by late 1942, “Wehrmacht requisitions of approximately 240 million Norwegian crowns” represented “339 percent of tax revenues and 95 percent of the gross national product.”

8

Other books

Pass The Parcel by Rhian Cahill

Rogue by Katy Evans

Hercufleas by Sam Gayton

The Grimm Chronicles, Vol. 2 by Ken Brosky, Isabella Fontaine, Dagny Holt, Chris Smith, Lioudmila Perry

The Substitute Stripper by Ari Thatcher

El Narco by Ioan Grillo

Whiplash by Yvie Towers

His Love Endures Forever by Beth Wiseman

Without Mercy by Belinda Boring

Overpowered (Powered Trilogy #2) by Cheyanne Young