Hitler's Last Witness

Scribe Publications

HITLER'S LAST WITNESS

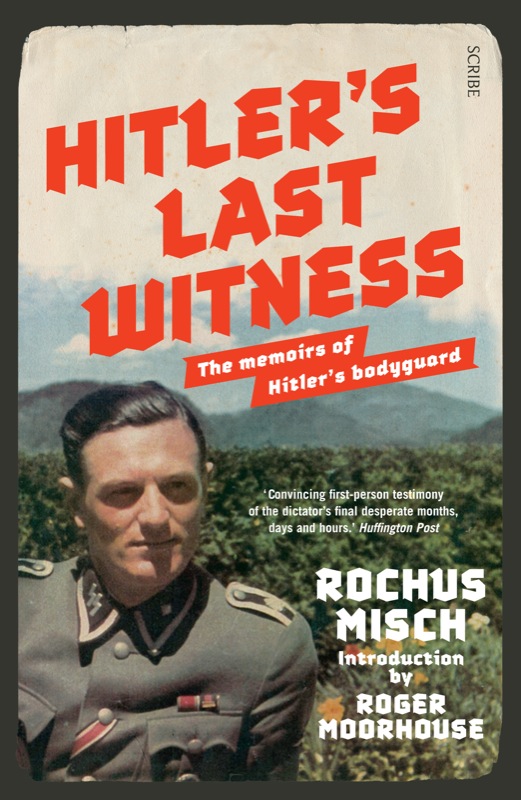

Born in 1917, Rochus Misch was recruited into Hitler's SS-bodyguard in 1940. He served as a bodyguard, courier and telephonist for five years. After Hitler's death he was held in Russian captivity for nine years. He died in 2013.

Roger Moorhouse is the author of

Killing Hitler

and

Berlin at War.

Scribe Publications

18â20 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3065, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

Published by Scribe 2014

This edition published by arrangement with Frontline Books

Originally published in German under the title

Der Letze Zeuge

in 2008

Copyright © Michael Stehle, Ãberlingen 2013, 2014

Translation © Pen & Sword Books Ltd 2014

Introduction © Pen & Sword Books Ltd 2014

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Misch, Rochus, 1917-2013, author.

Hitler's Last Witness: the memoirs of Hitler's bodyguard /Rochus Misch;

introduction by Roger Moorhouse.

9781925106107 (paperback)

9781925113389 (e-book)

1. Misch, Rochus 1917-2013. 2. Hitler, Adolf, 1889-1945. 3. Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter-Partei. 4. Schutzstaffel. 5. Germany. Reichskanzlei. 6. NazisâHistory. 7 World War, 1939-1945âPersonal narratives, German. 8. GermanyâHistoryâ1933-1945.

Other Authors/Contributors: Moorhouse, Roger, author; Michael Stehle, co-author; Professor Jörn Precht, co-author; Ralph Giordano, co-author; Regina Carstensen, co-author; Dr Sandra Zarrinbal, co-author; Geoffrey Brooks, translator.

943.086092

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

Contents

2

Conscripted Soldier: 1937â1939

5

My Reich â The Telephone Switchboard

6

The Berghof, Hitler's Special Train and Rudolf Hess

8

FHQ Wolfsschanze, FHQ Wehrwolf, Stalingrad, My Honeymoon: 1942

9

The Eastern Front Begins to Turn West: 1943

12

Preparing the Berlin Bunker: FebruaryâApril 1945

13

Bunker Life: The Last Fortnight of April 1945

14

Hitler's Last Day: 30 April 1945

15

Negotiations and the Goebbels's Children: 1 May 1945

17

My Nine Years in Soviet Captivity

18

My Homecoming and New Beginnings

Preface

I NEVER INTENDED TO

write my biography. In the course of my life I granted countless interviews to authors, newspaper reporters, historians and television teams from all over the world, rather fewer from Germany. It has all been said, so I thought. The fact that the questions reaching me by post and telephone over the last few years have increased, and not the opposite, taught me otherwise. The letters are overwhelmingly friendly and interested, and they come mainly from young, often very young, people. I have a bad conscience about having left so many unanswered. I am an old man and can no longer handle the onslaught. Not long ago I decided to go ex-directory; many international telephone calls came at night, because of the time lag. For decades my telephone number had been in public directories, but now the interest in me has grown so large that I have had to protect myself in this way.

Why has this interest expanded? I think that with the increasing passage of time since the 1933â45 period, young people simply have fewer worries about digging up the past than the previous generation. For them, it is perfectly clear that one can only learn from history if one knows it. And what is written in the history books has for some time not answered everything. In addition, I have to state this soberly and with resignation â there is the race against time. The opportunity will not exist much longer to put questions to such eyewitnesses as myself.

This book is, therefore, for me first of all an unburdening of my workload; henceforth, I can refer interested people to my memoirs. From very recent documentaries about events of which I am today the last surviving witness, I have become aware that my impressions may be an important source for understanding. I observe that certain representations which I know for certain to be false â or that in any case I saw, perceived or recall the basic events and circumstances differently â threaten to become historical fact. I would now like to explain what IÂ mean.

As a result of my involvement with the American film-makers of the Hollywood drama

Valkyrie

in the summer of 2007, I became aware that numerous errors of fact were presented in the public domain. This was a film about the failed attempt on Hitler's life on 20 July 1944. I was asked all things imaginable, from routine security measures to Hitler's habits. The team appeared well informed, yet I was surprised at so much incorrect presentation.

I noticed this particularly some time before in connection with the sensational world release of

Der

Untergang

(

Downfall

) â an important film, if a comic-opera type tragedy. âI' was to be seen in a couple of scenes: the representative of my person did not have a speaking role. It was shown how this actor discovered the bodies of the generals Wilhelm Burgdorf and Hans Krebs after their suicides. Why was I not asked how it really happened? Then they might have learnt that I did not react in the least in a calm, almost business-like way, as the film showed. On the contrary, I was extremely agitated to find that Burgdorf, whom I touched gently to tell him he had a telephone call waiting for him, had not nodded off, but was dead. I went off immediately to report the deaths of the two generals. A detail. Nevertheless, it gave a false impression, for I was anything but composed at that moment.

In the final hours in the Führerbunker, one thought above all others made me panic, and it had nothing to do with the Russians or the dead Hitler, but Gestapo Müller! I had seen the head of the Gestapo at RSHA (SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt/Reich Main Security Office) in the New Reich Chancellery. His presence was completely strange. Hannes â a technician who had also remained to the last in the bunker â and I speculated whether we would now all be eliminated. Maybe they would blow up the bunker? Better to destroy everything than have it fall into the hands of the Russians â and we had to reckon that that might go for us too. Was nothing and nobody to escape the Führer bunker?

During April 1945, silence â a deathly silence â reigned in Hitler's bunker flat below the garden of the Old Reich Chancellery. There was no excited coming and going. The actual Führerbunker consisted of a couple of small cell-like rooms. Apart from Eva Braun, only Hitler's valet, and his physician Dr Morell, had rooms in which they lived; later, Goebbels moved in with the doctor. All other rooms were for official purposes. Only by my small telephone switchboard was there a âpublic' sitting area to offer anyone. The portrayed hectic scenes before the end in

Der Untergang

â most of them occurred in the cellars of the New Reich Chancellery, many in the ante-bunker. The film had almost everything played out in Hitler's bunker apartment, to which only a few ever came, if summoned to âthe boss'. In the Führerbunker, deeper underground than cellars and the ante-bunker, death had already taken up lodgings long before Hitler put the gun to his head. The war could only be heard from the ante-bunker and in the Reich Chancellery cellars. In Hitler's domain there was only some shaking and dull noises to be felt and heard. On the other hand, it was not possible to know about events in the deep bunker if one was in the ante-bunker or in the remote cellars of the New Reich Chancellery.

The day before the release of

Der Untergang

in Berlin, I received a telephone call in the late evening. It was somebody from the production team letting me know that I had been requested not to appear at the première. No reason was given. Five weeks later, producer Bernd Eichinger visited me at my Berlin house. He was researching something new. Mentioning

Der Untergang

, Herr Eichinger referred to the book of the same name by Joachim Fest, which had been the basis for the film. They had set store by it, and my role was based on it. Yet Herr Fest had never spoken to me personally.

I was barely twenty-eight years old when the Third Reich went down. After Hitler's death I maintained the telephone connection to the Russians, and after my official release by Reich chancellor Joseph Goebbels, I removed all the plugs from the telephone installation. For five years â the last five years of Hitler's life â I lived wherever Hitler lived: in the Führer-apartment in the Old Reich Chancellery, in the Führer-HQs and finally in the Führerbunker.

I am an insignificant man, but I have experienced significant matters. Many thought â in connection with their relationship to Hitler â they should make themselves seem less or more important according to how the information was to be used. I saw no reason why I should do any such thing. I was always an apolitical person.

Completely in contrast to my wife, who was an SPD (Social Democratic Party) politician, even at one time a member of the Chamber of Deputies in Berlin, I was never a Party member, neither of the SPD nor of the NSDAP (National Socialist Party). I never volunteered for the Waffen-SS. I was recruited for the

SS-Verfügungstruppe

(VT), enticed by the possibility of state service. I would like to have gone into the Reichsbahn (state railways). Only later did the SS-Verfügungstruppe become the Waffen-SS.

[1]

Having recovered from a serious wound in the Polish campaign, and back with my unit, one day my company commander chose me for a post at the Reich Chancellery. I went there as ordered, and the following day, either 1 or 2 May 1940,

*

I began service there. My new boss was Adolf Hitler.

Today there are long debates about whether Hitler can be portrayed as a âprivate' man at all, even as âa person', but it is very difficult for me to separate the two. I knew him only as a person. A person who was my boss and to whom my welfare was important. He was a boss who had his own physician examine me when I felt bad; who spontaneously gave permission for me to be absent to see a girl; who upon my marriage sent me two cases of the most select wines and made a special payment assuring my life in the enormous sum of 100,000 Reichsmarks; and who never shouted at me. If nevertheless I felt a little uneasy in his presence, that was simply because he was âmy boss'.

I tried to carry out all my duties to the best of my ability, as was expected. While doing so, I enjoyed the many liberties my service often brought in its train, and I played pranks on those colleagues with whom I had a good relationship. I was careful to avoid blunders, such as made by two of my colleagues when they created model panzers for their children after seeing a demonstration of new weapons; this got them sent back to the fighting front. Heavy field boots sinking into mud and filth instead of extra-light, dazzling, made-to-measure boots on thick carpet â no thank you. Conscious of the front, I was careful to present myself exactly as the man who had been selected expressly for my task â somebody who gave no trouble.