Hitler's Rockets: The Story of the V-2s (23 page)

Read Hitler's Rockets: The Story of the V-2s Online

Authors: Norman Longmate

The Arnhem operation, although it had failed, did give London a temporary respite. Kammler’s batteries, after occupying two streets, had then taken over the whole Wassenaar district of The Hague. From 10 to 12 September a large house known as the Beukenhorst residence was the firing area, and from 13 September a newly cleared road, the Oud Wassenaarse. The air-drop at Arnhem on 17 September exposed the whole of Abteilung 485 to the risk of being cut off, and its two batteries were now withdrawn to Overveen near Haarlem and then to Burgsteinfurt, north-west of Münster, about 40 miles inside Germany, while Kammler moved his headquarters from Nijmegen to the same area. Battery 444, ‘Dornberger’s own’, had hardly reached Walcheren Island after its abortive attack on Paris from Euskirchen, on 14 September, when, around 17 September, it had to take the road again, to Zwolle, 36 miles north of Arnhem and about 10 miles inland. By now the three batteries combined had fired 35 rockets, of which – though Kammler did not know this – only 9 had exploded harmlessly in mid-air or plunged into the North Sea. On Tuesday, 26 September, the last survivors of 1st Airborne Division on the far side of the Rhine were withdrawn and, though the British still held a salient 60 miles deep on the south bank, the Germans occupied, securely it seemed, most of Holland, from which they could bombard both Antwerp, the major port on which the Allies depended, and Great Britain itself.

The Russians, who had clamoured for a second front to relieve the pressure on their armies, showed little gratitude now it had been established. Blizna, while still in use as the main V-2 development site, had not been bombed by the Russian air force, and – as the Germans had guessed – the Russians refused to allow Allied aircraft to attack it from Russian soil. By 27 July the Germans had abandoned it and on 29 July the party of British experts sent to study any material left there was on its way, a roundabout journey via Cairo, Teheran – where they were kept waiting for Russian visas – and Moscow, where they were kept waiting again, on the totally untruthful grounds that Blizna had not yet been captured. Only on 3 September, after the personal intervention of Anthony Eden, did they finally reach their destination, to find the research site deserted but undamaged, though fighting was still going on five miles away. The Germans had removed most of their equipment, but much useful information was gained from local informants and crater measurements, as well as from items left behind by the Germans, including a fuel tank, a useful pointer to the rocket’s range, and, in a latrine, part of an A-4’s test record, which clearly identified one of its fuels as oxygen, while other evidence confirmed that ‘

B-Stoƒƒ’

was alcohol, which several Poles recalled smelling in the remains of crashed rockets.

A little earlier all this information would have been invaluable ; now it had been overtaken by events, and the expedition ended in anticlimax. By 22 September its members were on their way home, but when, a little later, the crates they had so carefully loaded arrived it appeared that their contents had, on the way, undergone a mysterious change into ordinary aircraft scrap. The material from Blizna remained in Russian hands, for the Russian rocket scientists and engineers to study at their leisure.

A SPLASH IN THE MARSHES

We . . . saw only a kind of waterspout as they fell in the marshes.

Member of Anti-Aircraft battery, recalling service in Norfolk, October 1944

The opening of the rocket offensive, so long delayed, delighted Hitler, who now suffered another of his volatile changes of mood. ‘The Führer considers’, noted Albert Speer in his office diary of 23 September, ‘that the resumption of A-4 production at peak capacity –

i.e.

rapidly rising to nine hundred – is urgently necessary.’ Already Kammler had launched a secondary offensive, on 21 September, against a number of continental cities, principally Antwerp, though Liege, Lille, Tourcoing, Maastricht, Hasselt, Tournai, Arras, Cambrai, Mons and Diest were also to be the target, at various times, for from two to twenty-seven rockets. The campaign benefited Great Britain by absorbing many missiles that would otherwise have been aimed at London, but the main cause of the reduced weight of the attack after its impressive opening fortnight was technical failure. 485 Battery, of Group South, based in Germany and bombarding French and Belgian cities, suffered more than the units in Holland. Several missiles during the last ten days of September crashed back on to the launching pad, or plunged to earth within a mile or two of it, one particularly notorious rocket even setting off back into Germany, until blown up by an emergency radio signal. Kammler had no doubt that defects in manufacture, for which Dornberger could ultimately be held responsible, were to blame. Dornberger in his turn was equally convinced that it was poor handling in the field that caused the trouble. ‘Storage and rain caused the bearing bushes to swell in the trimming servo-mechanism. Replacements were not forthcoming.’ The truth was that the liberation of France had thrown out all the Germans’ elaborate plans for rapidly conveying the rockets from factory to firing point, via main storage dumps and forward supply depots. The vast bunkers in which highly trained speciaalists tuned up every missile into perfect condition shortly before it was launched were now heaps of rubble, and in Allied hands. Instead the rockets had been parked in temporary transit dumps, exposed to wind and weather, so that the highly sensitive electrical and mechanical components had become corroded – and only one of several thousand parts needed to fail for the whole missile to become unreliable.

Once he had diagnosed the source of the trouble Dornberger took energetic measures to put matters right:

Rockets ceased to be stored in the ammunition dumps. Immediately they came off the production line at the Central Works, express transport took them to the front and they were fired within three days. . . . Technical teams were detached from Peenemunde to the operational units to help in assembling newly introduced components. The first echelon of my staff . . . went to the operational area. It looked after transport, delivered the rockets to the batteries and ran the supply of spare parts. After this there were hardly any breakdowns.

The new supply arrangements, known as

Warme Semmel

(Hot Cakes), meant that rockets, though still transported to the launching area by rail, were then taken on by road to an assembly and testing point, where they were immediately inspected, and then sent on to the launching site. At the same time, Kammler and Dornberger managed, at least to some extent, to bury their differences. On 30 September 1944 the two men came to a formal understanding, enshrined in a written agreement which both signed:

Kammler took over field operations and had power of decision on fundamental questions. I was not made subordinate to him. . . . I was his permanent representative at home; as inspector of long-range rocket field units I had control of their formation and training; as his technical staff officer, vested with his own powers, I ran development and supply.

By now the central works was turning out 600 rockets a month and, as Dornberger was aware, ‘the conveyor belt equipment . . . could have doubled this figure without any trouble’, but the real bottleneck was fuel. The output of alcohol was barely sufficient even for the present production of rockets, while liquid oxygen, he complained, ‘also became a restricting factor after the big underground generating plants at Liege and Wittringen in the Saar had been overrun’. The figures spoke for themselves. The total supply ‘did not exceed the output of 30 to 35 generators’, each of which could produce about 9 tons of liquid oxygen, but by the time ‘the oxygen had been transferred from the factory storage tanks to the 48 ton capacity railway tankers’ and ‘thence to the 5.8 ton road tankers’, there had been a substantial loss through evaporation and another 5 lb per minute disappeared through the same cause while the rocket stood waiting to be launched, so that the original 9 tons had shrunk, by the moment of lift-off, to only just enough – 4. 96 tons – to fill its fuel tank. This powerful but hard-tohandle liquid, which had proved the key to the rocket’s success, was also, therefore, its Achilles heel, and its lack affected development work as well as operations. His teams had, Dornberger considered, a totally inadequate number of rockets available – 5 to 7 a day – ‘for experiments and acceptance tests’, leaving ‘28 to 30 rockets per day for operations’. To Kammler, he was aware, ‘the only important thing was the number of operational launchings. He wanted to report as many as possible to higher authority and whether they were effective seemed for the moment to be a matter of indifference.’ Dornberger, by contrast, a scientist before he was a soldier and an artillery man before he was a general, remained a perfectionist, eager to produce an accurate as well as a long-range missile – and, in his view, the A-4 was ‘still not fully developed’:

Dispersion was too great, effect was unsatisfactory because of the insensitive fuse, and a few rockets still blew up towards the end of the trajectory. We had to eliminate these weaknesses and also to devise optical, acoustic and radio means of recording the impact, which could no longer be observed from aircraft over the target areas. . . . Success in the experiments depended on a reasonable supply of rockets for the purpose. . . . A single series of launching tests lasted for weeks. Alterations and improvements took months to come through. On the other hand the front cried out for faster delivery and higher production.

Dornberger had one powerful card to play in seeking more rockets for deveopment, for ‘the withdrawal of the front called for longer ranges’, and here the scientists’ work bore rapid dividends:

We were able by making some minor improvements in the standard rocket . . . and by slightly increasing the contents of the tanks to increase the range of operational missiles to 200 miles. Some trial missiles with even larger propellant tanks achieved a range of 300 miles when launched from Peenemünde.

All this boded ill for the British, for it would mean that the Midlands, as well as the ports of south-east England, would be exposed to attack, provided Kammler retained his foothold around The Hague. This, however, began to seem uncertain. The Arnhem offensive threatened to cut off his troops, and he ordered a hasty retreat northwards. Between 19 and 25 September no rockets at all were fired against England, while 444 Battery re-established itself on the mainland north of Zwolle, near Staveren in Friesland, the promontory between the Zuider Zee and the North Sea. The only British cities now within his reach were Norwich and Ipswich, of which the former was the more attractive target, though its size – it had a peacetime population of about 130,000 – meant that he had little hope of hitting it except by chance. Nor were missiles falling wide in the surrounding county likely to cause many casualties. Norfolk was the third largest county in England, with a mere half a million inhabitants spread over 1.3 million acres. Ipswich, with its 110,000 residents, was even smaller than Norwich, while east and west Suffolk combined were not much more densely populated than Norfolk, with 400,000 people to 900,000 acres.

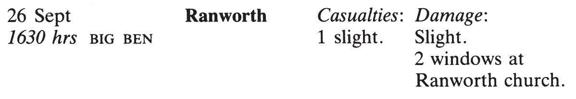

The rocket campaign against Norwich was such a fiasco that probably few of its occupants even realized they were under attack. Norfolk was ultimately credited with 29 incidents within the county boundaries, though the Germans are believed to have aimed 43 V-2s at its county town. The first, a harbinger of those to follow, came down 20 miles from its intended target, and in the wrong county, at Hoxne in Suffolk, at 7.10 p.m. on Monday, 25 September 1944. It was not even audible in Norwich, where people for the first time heard the double bang, now so familiar in London, the following afternoon. The explosion, according to a local historian, caused bewilderment in the city, since ‘no information could be otained as to its origin’. The rocket had in fact landed 8 miles to the north-east in an area well known to holiday-makers on the Broads, as the incident sheet in the county Civil Defence War Diary recorded:

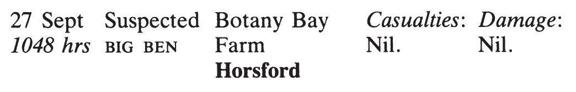

Next morning, another explosion in a village 6 miles to the north produced more puzzlement. Again the War Diary tells the facts:

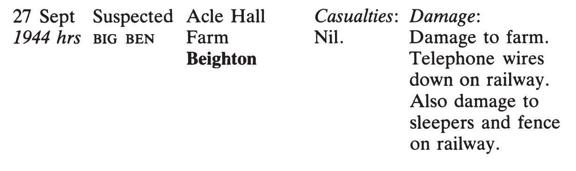

As yet even the police and Civil Defence workers on the spot were uncertain about the reason why the rich Norfolk soil was suddenly erupting into the air. The Horsford incident – its original name, ‘Horse-ford’, was a reminder of the rural nature of the area – was at first reported merely as ‘Double explosion and column of smoke’ and was not correctly identified until an hour later. Kammler’s next shot, landing ingloriously in a sewage works while disturbing the teatime peace of rural Whitlingham, was also not immediately recorded for what it was by ‘Control’ in Norwich:

The destruction done, though annoying, was hardly of a kind likely to bring the British government to its knees; nor was that which 444 Battery accomplished an hour and a half later, 9 miles east of Norwich:

Lunchtime had always been a favoured period for the flying-bomb bombardment of London and perhaps the Germans imagined that the people of rural Norfolk conformed to the same pattern, for their next rocket landed at 11 minutes past 1 p.m. on 29 September, carving out a 12-foot-deep crater at Hemsby, 16 miles north-east of Norwich and hurting no one. Six civilian houses and shops were damaged and about 60 military and naval bungalows, the nearest to a military objective the Germans had yet hit in East Anglia. By now the nature of the attack was beyond doubt and Big Ben struck twice again that day. At 1942 hours, as the War Diary recorded, two people were slightly hurt and 27 houses damaged, at Coltishall, a town of about 1000 inhabitants 8 miles north of Norwich; and at 2041 hours a rocket landed at Thorpe, 16 miles in the same direction. This now became almost the standard pattern of the bombardment, with one or two rockets a day landing well wide of the target and causing only minor, local inconvenience. On 30 September, eight houses, a farmhouse and a barn were damaged at Acle, but no one was hurt; on the following day a farmhouse was badly damaged, and five houses lost slates or windows at Sycamore Farm, Bedingham, rendering six people homeless, some of them evacuees who had sought safety in the depths of rural Norfolk, while three adults and two children were slightly injured.