Hitting Back (17 page)

Authors: Andy Murray

Celebrating my first

win, shaking hands

with George Bastl on

court two. So happy!

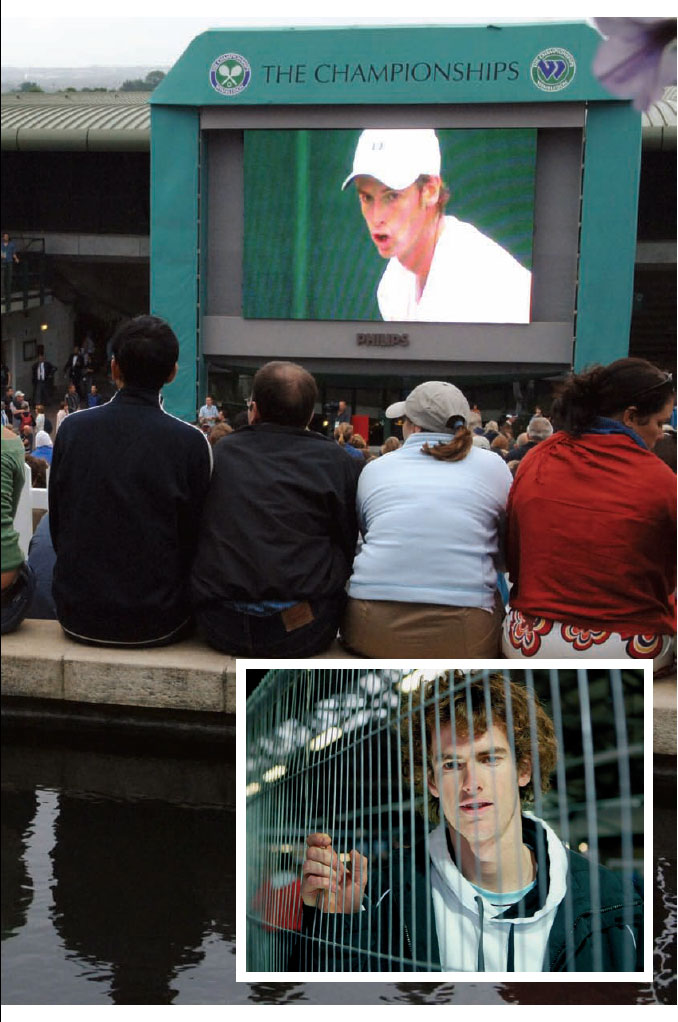

First appearance on the big screen at Henman Hill

(

Inset

) Looking through

the bars outside the

All England Club

during a photo shoot

with Tim Henman in

2006. Hair's starting

to get big!

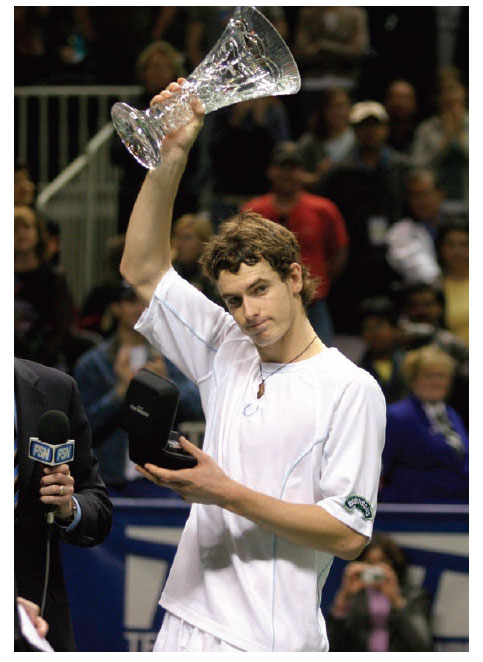

San Jose –

first ATP title.

Loving it!

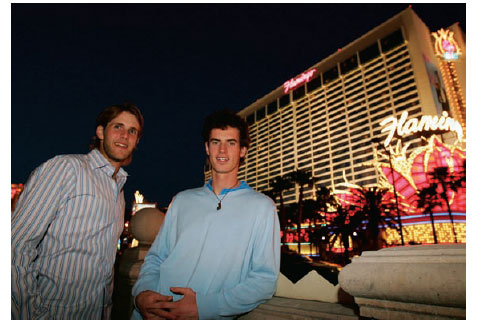

With British player

James Auckland

in Las Vegas

I can remember running round with Andy when we were little kids

at the tennis courts in Dunblane. My mum was coaching somebody

and we were at the back of the courts, chasing after tennis balls and

probably getting hit by some as well. When we got bored with that

we would go over to the park, kick a football and chase the

ducks while one of the other mums looked after us. We were quite

close in age so we did pretty much everything together and got on

pretty well. We argued as all brothers do, but mostly it was all in

good fun.

At home we'd make up games all the time and they were always

competitive. Sponge ball football in the hallway was a favourite or

indoor short tennis in the living room with all our trophies lined up

as the net. We'd put the bigger ones at the end for the net post and

the smaller ones in the middle. It was a bit silly but we loved it. I can't

remember breaking any ornaments, but when we were five or six we

once played basketball using a closed window as the hoop, so the first

time we threw a shot we smashed the window. That was very, very

stupid. My mum wasn't too pleased but my dad just sighed and said:

'We'd better get another window.'

As boys, we were similar in many ways but different too. Andy was

quite fiery and stubborn; I was more easy-going. He didn't like being

told what to do and he didn't always listen to what you had to say.

He doesn't even now. He liked to figure things out for himself – he

still does – and that can be a bit frustrating at times.

When we were kids, he'd often refuse to play what I wanted and

we'd end up arguing. I guess we had disagreements over silly things.

But we didn't fight. We maybe threw a punch or a kick, but we

wouldn't be scrapping it out over ten rounds.

I am the elder brother, so I would tend to win at games the

majority of the time. I usually beat him at tennis until we were about

twelve and thirteen – then Andy improved a lot and started to beat

me. He was so competitive, he wanted to win at everything, even

Snap. I admit, I used to let him win sometimes. I liked winning, but not

to the point he did. I wouldn't get mad if I was losing at Monopoly or

Cluedo or whatever, but he did. So, anything for a quiet life, I thought.

It was better to see him with a smile on his face than throwing a

tantrum – it was just less hassle.

We shared a room until we were about ten. I was much tidier. I

didn't like mess. Even if I was a bit untidy, it was controlled mess.

My clothes would be folded up on the floor as opposed to Andy's

dirty clothes in a heap. We had bunk beds and loads of posters all

round. Mine were Manchester United, his were Liverpool. Then we

became fans of WWF wrestling. I was a Hulk Hogan fan, and Andy

loved The Rock. Of course, we tried the moves ourselves. We

made a couple of belts out of cardboard and put duvets on the

floor for a stage. But I only ever let him win the women's belts, if I

was feeling generous.

We were always competing at something. Neither of us was happy

just sitting around in the house playing computer games all day,

although we had Game Boys and Nintendo. We'd much rather be

out playing football, tennis, squash or golf. I played quite a bit of golf

up to the age of seventeen and got down to a handicap of three

before tennis took over. Maybe it runs in the family: my uncle Keith,

Mum's brother, is a professional in America.

Andy and I never did anything really naughty growing up. We never

got into trouble at school and never experimented with smoking or

underage drinking but we were once in a bit of trouble for chucking

eggs with some friends at Halloween. We would wind each other up

a lot, but the only time I really hit him was when we were on a

minibus coming back from the Solihull tournament. He had beaten

me in the final and was going on and on about it. He had his hand on

the armrest and I punched him right on the nail of a finger. There was

a bit of blood and my mum had to stop the bus to sort us out. I didn't

think it was that bad but the nail went black and blue and eventually

fell off. He even had to get a tetanus shot the next day. He still talks

about it and shows off the scar. I do regret it, but everyone has their

breaking point.

I don't remember Mum telling me off really badly afterwards. I am

sure she was annoyed but she was also understanding. She was – and

is – a great mum to have. Dad is great as well. Even though they

separated when we were teenagers, I've always thought we had a

really good childhood and were brought up pretty well.

Looking back, it's strange that I wanted so much to go away from

home when I was twelve. I loved being at home but I had this fierce

ambition to board away from home because I wanted to be a tennis

player and I thought that's what I'd have to do. I ended up at the

LTA Tennis Academy in Cambridge. It was a rushed decision

because I'd been told that my original choice, Bisham Abbey, was to

be closed down, just four weeks before I was due to go. Everything

had been arranged for Bisham Abbey and I was going to be looked

after by Pat Cash's old coach, Ian Barclay. I'd known since the

February that I would start in August and my bags had been packed

for months! I was really excited and when things changed suddenly,

I still wanted to go somewhere. The new regional centre at

Cambridge was the option given to me by the LTA and it was a

mistake. I was twelve years old and I didn't like it at all. My tennis

suffered and I was often miserable on the phone home to my mum.

My friends were at the same training academy, but I was a little

younger than them so I was sent to a different boarding school. It

would have been logical to come home sooner as I was so unhappy,

but I wanted to try and stick it out – maybe I thought it was the

brave thing to do. I stayed eight months in the end and then enough

was enough.

Going away for that time meant that Andy and I didn't really see

much of each other and my experience definitely put him off leaving

home for his tennis. Three years later when he was fifteen, he went

away to Spain, and though I was still competing we were nearly

always at different tournaments. Even though we're very close in age

– only fifteen months between us – it is really only in the past two

years on the tour that we've been able to hang out together.

Things haven't changed that much since we were kids. We're

pretty similar and we get on really well but we still argue about all

sorts of things. I think that's normal. Andy still doesn't like being told

what to do. Sometimes I get a bit annoyed with that. But he's his own

person. I don't interfere with his decisions because he won't

necessarily like what I say. It's not worth arguing. I think I'm more laid

back than he is. Even if I'm doing something I don't want to, I still put

on a smiley face and do it, whereas I think Andy is more likely to look

completely fed-up.

I am very proud of what he is achieving in the game. He deserves

it because he has put in the work. He's overcome so many ups and

downs. I am sure in the next five to ten years he'll become a great

player. I don't think there's any doubt about that. I guess he's inspired

me to try to reach the level he is playing at. Obviously I'm not up to

his standard, but in the doubles, with my partner Max Mirnyi, I am still

playing on the ATP tour week-in, week-out. I'm loving it. I'm living the

life I always wanted to lead.

Can I Also Ask You This?

In 2007 I stopped talking to the BBC. There were a number of

things that contributed to the silence, but the main reason was

an interview that I did with one of their journalists at a smaller

tournament in Metz. He said he was interviewing me about

one thing, but it seemed to me more like a covert operation to

get me to talk about something else entirely. Something that

then dropped me into a whole heap of trouble.

Some people, I understand, would just let this sort of thing

go. I am one of those who can't do that. If I think something is

wrong or unfair, I will say so. It makes my life harder in many

ways, but I have never changed. It is just the way I am.

The situation arose out of nowhere. I was playing in one of

the smaller ATP tournaments in Metz in France, my first visit

back to Europe following the wrist injury that wrecked half my

year. I was playing in the singles and also in the doubles with

my brother, trying to get back to match sharpness after such a

long lay-off. I wasn't anticipating any press interviews. It

wasn't the kind of tournament that the world's media would

find of great interest.

On this particular day, I was in a bad mood. My brother and

I had just lost in the doubles and I didn't play that well either. I

was just about to jump into my car and go back to the hotel

when the press woman in charge of the event ran up to say:

'Someone from the BBC is here, just wondering whether you

could do five minutes with him.' I said I didn't really want to.

'Well, they've requested it. I'm sorry. It's just a general chat

about the tournament.'

I had no reason to be suspicious because normally Patricio,

my agent, would red flag a situation that could be awkward.

But this time he had no idea it was happening. The ATP did not

send him their usual email about interview requests at

tournaments probably because it was one of the smaller ones

on the tour. Then a guy came up to introduce himself. I'd never

met him and I had no clue who he was. It turned out to be

Brian Alexander, a BBC journalist who had been trying to talk

to me for ages – so my agent Patricio told me later – because

he was doing some sort of investigative programme into the

state of British tennis. Patricio had said no, explaining that I

wanted to concentrate one hundred per cent on recovery from

the wrist injury. This guy didn't seem too happy about it. He

sent an email back just saying, 'would 15 minutes with me

seriously delay his recovery process?!'

So the man said to me: 'I don't believe we've met. Nice to

finally meet you. I just want to talk to you about some of the

smaller tournaments on the ATP tour and what life is like away

from the glitz and glamour of the grand slams. Is that OK?' I

said it was fine. No alarm bells were going off. It sounded

perfectly OK to me. I swallowed my tiredness and disappointment

about losing the match and tried to be as decent as I

could.

The interview began without any problem. He asked me

about the atmosphere in Metz, what it was like to play in

somewhere like an old school hall. He asked me about the

Davis Cup and whether it was important to me. I explained

how much I enjoyed it, although the scheduling could put a

huge strain on the body. Then he said: 'Can I also ask you this.

There's obviously been some negative stuff about tennis

recently. About betting and suspicious betting on odd matches.

Are you shocked about that?'

I answered truthfully, that I really wasn't surprised. I said it

because I'd been reading in newspapers that four different

players had said they had been offered money to throw tennis

matches. Arvind Parmar, the British player, was one; the

Belgian Gilles Elseneer was another. Gilles said that he had

been offered £70,000 to lose a match at Wimbledon two years

before. Dick Norman had also said he had been offered a bribe

to lose a Challenger match. A few guys had come out and

talked about it.

That is why I said I wasn't surprised. I also said that it wasn't

acceptable and that it was difficult to prove whether someone

was trying or not in a tennis match because they can do their

best until the last couple of games of each set and then make

mistakes or serve double faults. It is virtually impossible to

prove. I said it was disappointing for the other players, but

'everyone knows it goes on'.

I wasn't properly prepared to have a serious conversation

about something as sensitive as gambling in sport. In trying to

be helpful, I had blurted something out without really thinking

about it. I didn't mean to imply I knew matches were being

fixed, only that approaches were being made to certain players.

For the record:

He then asked me two follow-up questions on the same

subject. I should have realised what was going on – that this

was the whole purpose of the interview – but it was late, I

wasn't thinking straight and maybe I was a bit naïve. We were

talking about the fact that you couldn't stop people betting on

tennis and therefore it was difficult to stop potential problems

with players being offered money to lose.

He said: 'You don't sound surprised then. You actually feel

this is locker-room talk. You and fellow players know this kind

of thing is going on?'

I said: 'Yeah, I speak to a lot of guys, especially experienced

ones who have been around a long time. They obviously know

that it happens. A lot of guys have been approached about it.

I've seen articles saying guys even at Wimbledon are doing it,

so . . . everyone knows it goes on . . .'

Those were the words that came back to haunt me: 'Everyone

knows it goes on.' A few days later, Patricio called me and said:

'Have you been talking about betting? Because there is a guy

doing a show on Radio Five called

The Usual Suspects

and it's

about betting in tennis.' I said: 'Yeah, but I only answered a

couple of questions.' I didn't think I had said anything that

other people weren't saying. Tim Henman had been on

television saying that he thought betting on matches was a

growing trend because of the internet, and tennis would have to

be vigilant against it. John McEnroe had even talked about it as

a 'cheap way to make a buck'. So there were lots of opinions

out there and I didn't think I had said anything different.

Then the programme was aired and it was something like:

'We're talking about corruption in tennis. This is what Andy

Murray thinks about it.' Then it was my words: 'Yeah . . .

everyone knows it goes on.' They made it sound as though I

was saying tennis was a corrupt sport.

The BBC website made the situation even worse. On there

I was quoted as saying: 'Everyone knows corruption goes on.'

Many things seemed to happen very quickly after that. It

caused headlines around the world, the ATP told me I

shouldn't be saying such things; and some of my fellow

professionals like Rafa Nadal and the Russian Nikolay

Davydenko, who was being investigated following unusual

betting patterns on a match he lost in Poland, had a public go

at me. I just didn't think it was fair for a number of reasons.

The ATP ought to have found out what the BBC were

looking for when I was asked to do that interview. They are the

ones that asked me to do it, as one of our media obligations. If

they had said: 'No, sorry, he can't do the interview' or even if

during the interview, the representative from the ATP had cut

in and said: 'Sorry, you said you were here to talk about the

tournament, not ask questions about betting' they might have

solved the problem before it started. It was obviously a touchy

subject and the ATP woman was standing right next to me at

the time.

The context of this is important. It is a fact that tennis

players are not allowed to bet on matches, their own or

anyone else's. Neither are people in their entourages. There

was an Italian player called Alessio di Mauro who was

suspended for nine months and fined £29,000 for being found

guilty of betting on matches – not his own – but I thought the

punishment was a little bit harsh given that the reports said he

only bet a few lire. The real fear for tennis was a different

one: that players expected to win matches would be bribed to

deliberately lose them, so that criminal gamblers could back

the longer-odds opposition knowing they were likely to win.

So it was a real, live, dangerous issue. There was an investigation

going on into that Davydenko match against the lower

ranked Vassallo Arguello in Poland when Davydenko pulled

out in the third set with an injury and I think the ATP staff

might reasonably have intervened when they sensed what the

interviewer was after. Of course, you can blame me too.

Maybe I should have taken the responsibility myself – I do try

as I get older to do that – but I was taken by surprise, and I had

believed this guy when he told me he just wanted to ask about

the atmosphere at minor tournaments. At no point did he tell

me he was gathering material for an investigative radio

programme on match-fixing. If I had known that I wouldn't

have done the interview. I thought it was pretty poor.

It turned out that he had spoken to five or six other players

at Metz, all about betting. It was clearly his mission, but he

didn't mention that to me. In the programme that went out,

they just ran part of my answers and none of his questions so

the context was completely lost. Obviously we protested and

the head of BBC radio sport wrote a letter to me in part-apology.

The issue of betting is still there. I haven't said any more

about it than most people. Since that interview, Michael

Llodra, Arnaud Clement and Dmitry Tursunov have all come

out and said that people have approached them to throw

matches. It happens. We know that the approaches happen.

But I don't know anything else. They have been holding

investigations, but no one's been found guilty of trying to fix

their own matches.

It is not fair to say that tennis is corrupt and make it sound

as if those words are coming from me. I never once said that

tennis was corrupt. It is

my

sport. I couldn't give 110 per cent

every match, or even play it at all, if that were the case. I have

to believe in its essential honesty. I have never been offered

money myself and when I spoke I was going by what other

people had been saying.

I had a great deal of negative press afterwards. Nadal,

obviously, had read all about it. He said I had gone 'overboard'.

Davydenko clearly didn't like getting asked about the

subject in press conferences. 'If Murray says that he knows,

that means he gambles himself. This is outrageous. How does

he know what I was trying to do? I was so upset with the whole

thing I started crying.'

Both of them had received a message that I believe had been

badly distorted by the BBC's reporting. You don't want that

sort of issue with players. You spend thirty weeks of the year

with them. It's not the most comfortable thing if you're trying

to avoid them.

As far as Davydenko was concerned, it probably sounded as

if I was directing some sort of blame at him or saying he was

guilty. It was bad enough for him to be caught up in the whole

betting controversy, but it must have been pretty tough to take

when he was told that one of his fellow players was saying he

was guilty. I guess what he said in regards to me was a reaction

to that.

After I played him in Doha, I apologised to him for what had

happened. I never did have any kind of row with him because

we don't normally speak on the tour. I don't know him that

well. He doesn't speak very good English and my Russian isn't

that great.

As usual, I have learned from the mistake, but even now if

someone came to me and said: 'What do you think about

betting in tennis?' I am not sure what I am supposed to do.

Should I lie and say nothing? Should I say: 'No comment',

which basically makes it sound as though I think something

dodgy is going on. Or should I tell the truth? That is what I did.

I told the truth, which is what I was always taught growing

up. I didn't point the finger at any player. I just told the truth

as I saw it and then watched it get splashed round the world as

a headline.

So that is why I decided I wouldn't speak to the BBC. I felt

an important trust had been broken. It wasn't the only problem

I had with them either. I was on the shortlist for the 2007 BBC

Sports Personality of the Year Award and one of the things

they do on their website is a little 'Did You Know?' section

about all the contenders. Amir Khan's said: 'Did you know

Amir has a cousin who plays for the England cricket team?'

Mine said: 'Did you know that Andy Murray was called 'Lazy

English' when he trained in Spain?' That would be fine if it was

true, but I never, ever heard anyone call me that. I was baffled.

I asked all my friends who were at the Academy with me and

none of them had heard that expression either. It came from

nowhere and no one had bothered to check whether it was

actually true. Perhaps you shouldn't worry about what people

call you, but I had worked so very, very hard in Spain that it

seemed to me unjust.

Then there was Jamie winning the mixed doubles at

Wimbledon. Radio Five had asked me if I would come and

speak to them on the air after the match and I said sure. I went

along and did the interview, but as Jamie lifted the trophy, I

couldn't speak. I was crying. So Jonathan Overend, the Radio

Five tennis correspondent, cut in with the description: 'Jamie

Murray lifts the Wimbledon trophy . . .' etc.

Then this woman says to me on air: 'Andy, just before you

go – you must be jealous of Jamie. I'm an older sister and I love

it when I get one over on my little sister.' I looked at her in

disbelief. My expression must have said: 'What the hell are you

doing?' I didn't say anything. There was just a moment of

silence. I definitely wasn't jealous of Jamie, I was thrilled for

him. If I had been jealous I doubt I would have been in tears.

If you listen back to the interview, you can hear in my voice

that I can hardly speak without my voice cracking.