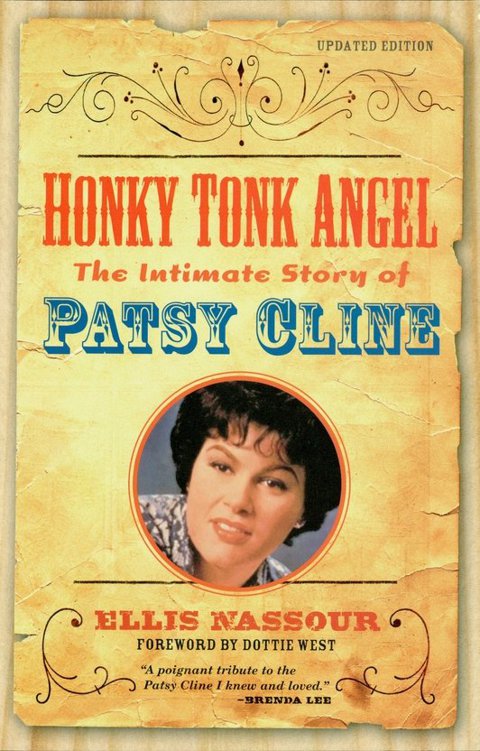

Honky Tonk Angel

Authors: Ellis Nassour

Cover design: Scott Rattray

Cover photo © GAB Archives/Redferns

Photograph appearing on half title page collection of Connie B. Gay.

Copyright © 1993, 2008 by Ellis Nassour All rights reserved

This book was first published as

Patsy Cline

by Leisure Books in 1981, then as

Honky Tonk Angel

by St. Martin’s Press in 1993. This updated edition is published in 2008 by

Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-55652-747-0

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

for

Hilda Hensley and Charlie Dick

and

Dottie West

. . . thanks for the memories

P

atsy Cline could never be summed up easily. The closest I’d come is to say that she was

real.

I first met Patsy in Nashville, my home town, in 1961 backstage at the Grand Ole Opry down at the Ryman Auditorium. In 1957, after I saw her on “Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts” and bought her record of “Walkin’ After Midnight,” I wrote Patsy a fan letter—the only fan letter I’ve ever written. And she answered it, saying she hoped we’d get to meet.

We did, after I finished Tennessee Tech, got married, and came back to town for Starday Records. I saw Patsy at the Opry and made a point of bumping into her. Before long we were good friends. Patsy would come in off the road, or I’d return home from a date, and we’d get together to talk shop. When I wasn’t working, Patsy took me on the road with her to help with her wardrobe.

More than anything, I watched her. And I learned from her. It was unbelievable the way I looked up to her. Patsy not only put feeling into her music but also her entire self. Until I studied Patsy onstage, I just sang songs. I knew I’d never be able to duplicate Patsy, and I became determined to try.

Patsy taught me how to show emotion, how to say the words with the feeling they deserved. She’d say, “Find one person to sing to and sing to just that one.” When I got that down, Patsy added, “Now make each person out there think he or she is that one and cast a spell over them.”

That was the best advice anyone ever gave me.

Patsy was born for show business. Her life was singing. When you saw her perform, you knew that nobody else came close. There’s no one around today who can! She had a charisma that was equal to Elvis or Johnny Cash, both of whom she admired.

She wasn’t just good. Patsy was sensational. I wish more of her had rubbed off on me. When she sang a ballad—you know, a real tearjerker—and you’d see her crying, Patsy wasn’t faking. She was into her music that much. She knew how to touch an audience. Patsy sang with such heart and feeling. Nobody could sing the blues like Patsy. Her troubles might have added to her greatness as a singer. And she didn’t have to have a microphone. Her voice was strong.

By the end of her set, she’d have the audience so wound up they were on

their feet. She said, “When you depend on the public for your future, you must be real with them.”

She enjoyed the recognition of stardom. When it came, she said, “Damn, it’s about time. I’ve paid my dues.” She loved signing autographs and posing with her fans for pictures. When she had a new record, we’d get the trade magazines and look for her song and watch it progress each week.

Like everyone, she had ego, but what amazed me was how she wasn’t afraid of competition. She knew how good she was and encouraged all of us. Patsy had a heart of gold offstage. She was always giving to all of us just starting out. The stories are endless—she gave advice, food, clothes, costumes, furniture. Once when she noticed I didn’t have anything special to wear around the house before going to bed, she bought me a bright royal-blue robe. It was the most gorgeous robe I ever owned. I lost it when my house burned.

About the only thing I saved was the scrapbook Patsy gave me the year before she was killed. We were crying over the trying times in the business and the ones our men put us through, and she suddenly said, “Hoss, I want you to have these.” When I got home, I was leafing through the clippings and mementos and a check for seventy-five dollars fell out with a note saying, “I know you been having a hard time.” It was the money we needed to pay the rent.

In the era we came up through, the women singers didn’t have the clout or the money-making potential they do today. And these were women who were stars in their own right. We were mainly used for window dressing. Patsy broke the boundaries. Her massive appeal proved women, without men by their side, could consistently sell records and draw audiences.

Patsy was bright If anyone thought differently, they were in for a surprise. She made the men—singers, musicians, record executives, promoters—respect the success she achieved. She was outspoken for our time. You never had to guess or read between the lines with her. You always knew where you stood. If you were her friend, she’d step in front of a locomotive to save you.

Patsy could be soft and feminine, but she could hold her own against any man. It was common knowledge that you didn’t mess with “the Cline.” If you kicked her, she’d kick right back.

Patsy’s voice was a unique one in the late fifties, when her impact was first felt. She didn’t birth the new Nashville sound, but followed close on the heels of Jim Reeves and Eddy Arnold in bringing it out of diapers. Hers were the first country female’s records to cross over into pop. She was discovered by an audience that most likely never would have found time to listen to our music.

Patsy was always so full of joy—on the outside. On the inside, she dealt with a lot of hurt and unfulfilled promises. She brought everyone such happiness, the saddest thing to me was that Patsy never found it in her own life except in her children. She worked so hard and was a star—I mean, a really big star—three years.

I recall Patsy’s last date in Kansas City as if it were yesterday. We shared a dressing room for the benefit concert. Though suffering with a terrible cold, Patsy went on and was so terrific she defied anyone to remember who’d been on before her. In between the three shows, she tried to rest but we talked.

That night she was exhausted, yet she went on and, as always, had the audience

on its feet. Watching from the wings, I could see she was moved. She tried to quiet them to a roar and shared some emotional things. At one point she said, “I never could have gotten this far without your support. I love you all!” It was obvious from the ovation that they loved her too. Patsy came offstage into my arms, crying.

The next morning, her manager/guitarist Randy Hughes’s plane was delayed indefinitely because of fog, but Patsy was impatient to get home. I talked her into driving back in the car with us. At the last minute, she changed her mind and decided to wait out the weather with Randy. Hawkshaw Hawkins and Cowboy Copas, veteran stars of the Grand Ole Opry, were to fly with them.

Two mornings later, I woke to a nightmare. We got news of the crash on the radio. Losing three prized entertainers hit hard, but for me it was worse. My Patsy was gone.

At Patsy and Charlie’s house she was laid out in the living room, according to her wishes. I put my hand on the bronze coffin and was cold and numb. I could hardly stand. I wanted to reach out to Patsy. She had been like my sister and there was so much I wanted to tell her. But it was too late.

I miss Patsy. I know she’s dancing with the angels and singing in heaven’s band. I think of her often but try not to cry. I cherish the past, yet I can’t live in it. Patsy prepared me for the future, making me a better person, a better singer. I thank God she was a part of my life. I hope that’s the way people remember me.

I wouldn’t exchange what we shared for anything. Patsy was the consummate artist and human being. There’ll never be another like her. She’s probably listening to me right now and laughing, “Oh, Hoss!” I can hear her.

—DOTTIE WEST

AUTHOR’S NOTE: After sustaining life-

threatening injuries in an automobile

accident en route to the Grand Ole Opry,

Dottie West died during surgery on

September 4, 1991.

W

hen I began researching Patsy Cline’s life, I envisioned telling the story of a simple girl from the Shenandoah Valley and the Apple Blossom city of Winchester, Virginia, who came up the hard way—determined to become a star. I was in for a surprise.

Most of my knowledge of Patsy came from working with Loretta Lynn in 1970. Through Loretta, I met Patsy’s second husband, Charlie Dick, a remarkably affable guy. In 1977 I wrote a magazine series to commemorate Patsy’s forty-fifth birthday. I had several interviews with Hilda Hensley, Patsy’s bright, charming, and devoted mother, and Charlie. Then came Loretta’s autobiography,

Coal Miner’s Daughter,

and the movie adapted from it. Suddenly there was an explosion of interest in Patsy Cline. I spent the summer of 1980 in Nashville, Dallas, Houston, and the Virginia/ Maryland area where Patsy lived. I interviewed a hundred family members and friends from Patsy’s early days through her final years of stardom. I returned to many of these same places and sources in 1991 and 1992 for this new, revised, and much expanded edition.

Patsy was simple, yet complex; gentle, yet volatile; smooth, yet rough; sweet, yet bittersweet; shy, yet outspoken. She had great strengths and weaknesses. Here was a woman not only twenty years ahead of the pack musically—the female singer responsible for changing the course of country music—but also twenty years ahead as a feminist.

Patsy was a woman who enjoyed life as it came and with great gusto. She wasn’t a beauty in the traditional sense, but, over and over, I heard of an inner beauty, warmth, friendship, and loyalty to those she considered dear. She was the first Nashville female superstar, equally at home in the recording studio, onstage, or on television. She was an innovator, though not always willingly, in what she recorded and how she recorded it. She set trends in style and dress that were mocked behind her back, then quickly copied. As a singer, Patsy had great range. Songwriter Harland Howard noted that writers couldn’t take full advantage of Patsy, since they didn’t have the ability to write for her voice. He noted that, had she set her mind to it, Patsy could have sung operetta.

This is a candid retelling of Patsy’s life—a story of the total woman. There are many wonderful memories and a few ugly incidents. It was important to me to

present the full story, because in learning of the complete woman that Patsy Cline was, not just the record artist, we see the fire that burned within her to create the trailblazer she became. I discovered facets of Patsy Cline that those closest to her—even her husbands and mother—weren’t familiar with. Some of these revelations haven’t set well with Charlie Dick and Hilda Hensley. I apologize for any unintentional hurt. It was the furthest thing from my mind. In fact, at all times I have gone to extreme lengths to be fair and objective to all parties. For especially troubling passages, I substantiate facts from at least two additional sources. Concerning controversial or questionable situations, I present an alternate take from another person or persons. Often I heard the same story from different people but the time frame and details weren’t consistent. I have made every effort to separate truth from fiction. Conversation between Patsy and others is quoted. In some instances, this is direct conversation to the best of an interviewee’s memory; in others, a conversation is used to flesh out scenes in keeping with the stories I was told. Some people recalled exact bits of Patsy’s conversation; in other cases, conversations were remembered in an interviewee’s words and not verbatim as they originally transpired.

Faron Young’s observations and recollections, for instance, are judiciously edited from eighteen pages of transcripts from our interviews in his office in Nashville in 1980.

This book wouldn’t have been possible without the selfless cooperation of the musicians, artists, writers, fans, friends, and family who knew Patsy Cline, Charlie Dick, Gerald Cline, and Bill Peer. They came forward with warm welcomes into their homes, offering remembrances, long-forgotten facts, and photographs. These wonderful people provided the oral history of Patsy Cline that I have edited and shaped into book form.

No one was more supportive of this project than Dottie West, who, on several occasions before her tragic and untimely death in September 1991—once during a crisis in her own life—interrupted her hectic schedule to give generously of her time and Patsy Cline artifacts.

Recording session and release dates came from the Decca Records archives I was allowed access to and Nashville’s Country Music Foundation.

March 1993 marks the thirtieth anniversary of Patsy Cline’s death. Her phenomenal revival in popularity across age groups and lifestyles proves she was no mere shooting star. In fact, Patsy’s more popular today—not only in the United States and Canada but also around the world (Australia, Britain, Scotland, France, Germany, Austria, Japan, Argentina, and Brazil)—than she was at her peak.

Patsy was the personification of the word original. Her life is testament to the saying “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.” I feel this is the story, with its inspiring ups and gritty downs, Patsy, had she lived, would have told.