Authors: Roxanne Bok

Horsekeeping (9 page)

Unlike Scott, I had been weaned on dogs. A largish white miniature poodle “JouJou” loudly growled his teeth into my diaper to tug toddler me from the freedom of the front yard. Unfortunately, once I was safe in my mother's care, JouJou would take off after his true passionâchasing every car on the road. He limped home from his last rampage to quietly die on the back door rug. Our subsequent small white toy poodle “Tigre” ate only table scraps and lived twenty-one years, toothless and blind but still perky to the end. Llaso apso “Boucher” served as child substitute to my empty-nester parents when I left for college. Alongside my immediate canine companions, my grandfather's sleek black mutt Velvet hid deep in the closet under the eaves when it thundered, and my aunt's clumsy rust-red Irish setter and my grandmother's series of graceful afghans showed me the pleasures of the larger breeds. I remember them all fondly.

Even the mean ones that scared me I revered. My cousin's grandparents had a boxer-pit bull mix named Butch to protect their one-room home down the port in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Butch would just as soon tear your head off as look at you unless called off in Polish by Bubba or JaJa. But that dog adored the old lady, and I can still see Butch with his front paws up on the chipped lip of the porcelain kitchen sink smiling broadly while Bubba brushed his gleaming white, lethal teeth.

Scott had only one childhood experience with a pet. Before he fully embedded into the household, a frothing springer spaniel named Rusty bit the neighbor kid's bottom and was shipped off to the pound. Too bad: if only his parents tried another dog, maybe Scott would be more interested in our growing animal family. But we are formed by early

experiences and follow our own inclinations. I make do with one house pet when I'd prefer several, and Scott had endured our problem child Peanut in our new marriage and now suffers my over-enthusiastic affection for our excellent Velvet. So in tune on almost everything else, we stare across a gaping divide when it comes to pet adoration. I envision other couples cozy on the couch, with a cat and a dog squeezed in between, waxing eloquent about their furry children, just as we do about Elliot and Jane.

experiences and follow our own inclinations. I make do with one house pet when I'd prefer several, and Scott had endured our problem child Peanut in our new marriage and now suffers my over-enthusiastic affection for our excellent Velvet. So in tune on almost everything else, we stare across a gaping divide when it comes to pet adoration. I envision other couples cozy on the couch, with a cat and a dog squeezed in between, waxing eloquent about their furry children, just as we do about Elliot and Jane.

I have not given up: someday he may surprise us all with a deep and abiding affection for a dog, a bunny, a cat or even a horse.

CHAPTER FIVE

Not Much of a Plan

A

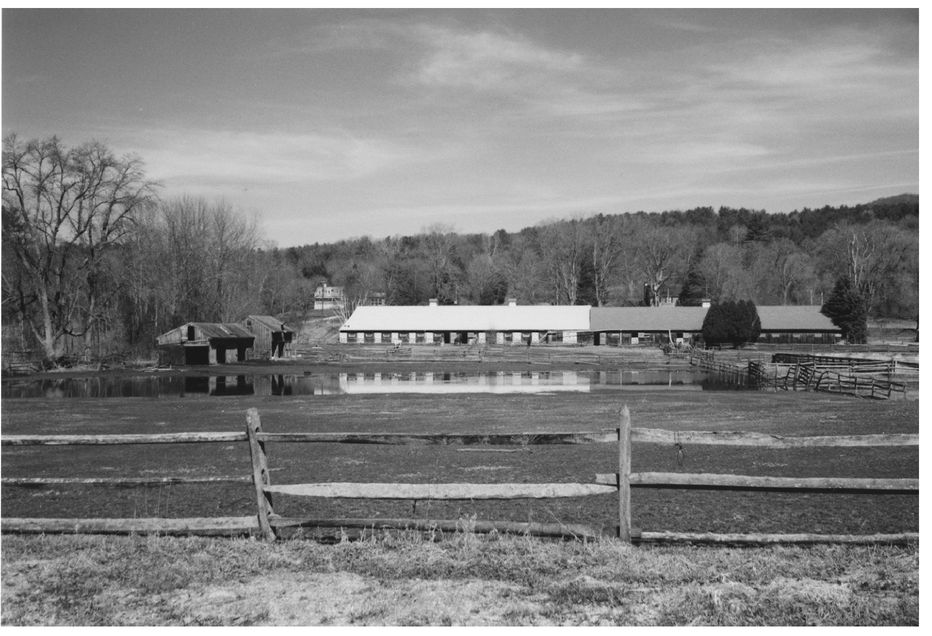

S OUR MAY 1ST CLOSING DATE for El-Arabia approached, we fully registered our limited experience. Our romantic excitement did not quite prepare us for the responsibility of operation. Now what do we do, just up and run it? Plug in a few horses and throw them some hay occasionally?

S OUR MAY 1ST CLOSING DATE for El-Arabia approached, we fully registered our limited experience. Our romantic excitement did not quite prepare us for the responsibility of operation. Now what do we do, just up and run it? Plug in a few horses and throw them some hay occasionally?

We had enough on our plates alreadyâtwo homes, two kids, too busy. Moreover, we were not horsey materialâwe liked things neat, clean and safe. We are sensible, practical people, and horses are not sensible, practical animalsâthey are expensive, delicate and needy. Scott, a lawyer turned investment banker, grew up in small town Michigan, dresses in hand-tailored suits and works all hours not dedicated to me, the kids and sleep. While he can readily put together a merger of two titans of industry, he crumples when faced by a six-year-old's unassembled hot wheels track or a “fun to do together” Lego space station. Talk of building a tree house turns him visibly pale. Although he claims to have picked cherries and asparagus for a nickel a pound as a kid, after twenty-plus years of marriage to the man, I still find it hard to believe.

Scott had ridden horseback only once, a trail ride I bullied him into when we first moved to Salisbury. As we raced along a wooded path, Scott's massive smart-aleck horse ran his knees into every close tree trunk and his head into all low-hanging branches.

“Duck,” our fifteen-year-old leader repeatedly yelled.

Scott's wrathful eyes bored into my back as we recklessly flew along the mountain trail.

I boasted a bit more experience. As an invincible teenager I rode western a few times at one of those backwoods operations where they took your money and cared little for your life. The horses meandered all pokey heading out from the barn, but look out once they turned for home. They would full-gallop back, and if you lost your grip you got dumped in the dust and left for dead. Later, when Scott and I lived in London, I hacked a few times in Hyde Park. The stable girls do not baby you there: their rule of thumb is that you are not a real rider until you've spilled a dozen times. Once mounted, ten or so of us would cross an unforgiving cobblestone lane and a honking London ring road to reach the park. The Dickensian charm attracted tourists, many who were riding virgins. “How hard can it be?” I imagined them asking their friends and spouses. “The British are so polite, so civilized.” Well, the British and their horses hide a wild streakâthey invented fox-hunting after allâand few of the uninitiated could anticipate the Rotten Row, a half-mile stretch of soft dirt where the horses like to let loose.

At the top of Rotten, our guide barked in Cockney English: “Those of you who fancy a gallop go on ahead. If not, hold your horses back and trot along.”

A few of us nervously cantered off. Horses sense incompetence in a nanosecond, and incompetents are useless at containing a thousand muscled pounds of herd animal hard-wired to stick with his buddies. So off everyone explodes in a pack resembling the Derby, faster and faster because once they get going, horses love to race. A few bodies go flying, and I had dismounted more than once to help collect the rider-less horses that wandered off to eat the emerald grass amongst the picnickers. One Japanese woman, who spoke no English but communicated fluently through the universal language of hysteria, refused to get back onâwho could blame herâand the two-leggeds led the four-leggeds in slow and dismal return to the stables, those quaint cobblestones clopping a more gothic music.

Once Stateside, I rode occasionally at local barns in Connecticut, content to hermetically seal myself in riding rings concentrating on how to walk, halt, turn, trot, and, to a limited extent, canter. But I had only minimal technique and had yet to tack up or groom a horse. My son, on the other hand, started riding at eight. He immediately possessed balance, rhythm, confidence, respect, and listening skills: an ideal rider young enough to take the punishment, like when the grumpy lesson horse Sultan bit Elliot's finger. He cried, hard, and I berated myself for encouraging him to feed the friendly horse. He also weathered his first fall, again courtesy of Sultan, a slow motion topple when the trot abruptly halted, and that mercifully I didn't witness. Shook up, but with more respect, he climbed back on.

After each of Elliot's half dozen lessons, we would hold Jane up on the saddle and walk her a few paces.

This was the sum total of our checkered past in the horse world.

And now we owned a horse farm?

What had we done?

Buyer's remorse took up residency in the stalls of our brains if not our hearts. A horse farm is reputed to be a black hole for losing money, a close third to roulette and the lottery, maybe tied with inn-keeping, a business Scott and I know a little something about. Since 1990 we have owned The White Hart Inn, the local watering hole that shelters leaf-peeping tourists and parents visiting their kids boarding at the resident prep schools, not to mention the regulars who imbibe at the popular tap room bar. Over two-hundred years old, it holds court on the village green as the foremost historic landmark in town. Its twenty-six rooms and restaurant have served the town well. The broad columned porch anchors a comfortable building with a patina that welcomes the casual and the posh. It seems everyone has a story about their experiences there, and no matter where Scott and I go in the world, we find six degrees of separation circling back not to Kevin Bacon (who has a house in the area and is an occasional customer), but to The White Hart Inn.

The White Hart “family” echoes a soap opera and it is probably best we do not know even half of what else goes on alongside business, but, all in all, inn-keeping has been fun. We further integrated into the community and, though the business will never support us, it steeled our nerves to our next unplanned adventure of horsekeeping.

The White Hart “family” echoes a soap opera and it is probably best we do not know even half of what else goes on alongside business, but, all in all, inn-keeping has been fun. We further integrated into the community and, though the business will never support us, it steeled our nerves to our next unplanned adventure of horsekeeping.

In three months we would close on the horse farm property and have to hit the ground running with repairs and renovations on that May 1

st

or lie dormant over the long winter. Not the types to postpone gratification, intuitively Scott and I objected to years passing with the farm horseless. But even the basics were undecided: should we lease the farm outright, maintain total control, or some combination?

st

or lie dormant over the long winter. Not the types to postpone gratification, intuitively Scott and I objected to years passing with the farm horseless. But even the basics were undecided: should we lease the farm outright, maintain total control, or some combination?

What we needed was an expert: a competent, take-charge, honest, likable farm manager who could ultimately run the business but start immediately advising us how to set it all up. Logical yes, but Salisbury offered a limited employment pool. This job required someone multi-talented, dexterous and independent. On the one hand, we didn't want to turn the place completely over to someone who ignored our input and evaded control; that was why we bought it in the first place. On the other, we could never educate ourselves, find the contractor, and oversee the planning, let alone the construction, from New York City in three short months. Scott may have purchased all the how-to books, which I gave a thorough read, but wisdom is realizing what you don't know. We wised up rapidly.

Word of our impending purchase grapevined through our small community.

“Have you heard that the Boks bought that old Johnson place? What do they know about the horse business?”

No doubt their chuckles descended to belly laughs with “They paid

what

? For

that

?”

what

? For

that

?”

In the eyes of the local population, weekenders possess more money than sense, spending it lavishly on the real estate (thereby pushing up prices and the cost of living) and then expecting the locally provided services

to come cheap. I am acutely conscious of the full-timers' angle of vision, their long witness to the forgotten years of slow-moving properties and declining values. But we've been here long enough to remember and to have been burned. We lost money on our first house in Salisbury. Buying at the top of the market in 1989, we resold ten years and many improvements later at the same price. But since 2002, it has been a stretch of rising prices. The vast sums people cough up for their Litchfield County real estate is general knowledge with all transactions, including names, listed in the local newspaper, along with fender-benders, bad checks, domestic disputes, and “doo-eys,” the vernacular for DUI and DWI citations.

to come cheap. I am acutely conscious of the full-timers' angle of vision, their long witness to the forgotten years of slow-moving properties and declining values. But we've been here long enough to remember and to have been burned. We lost money on our first house in Salisbury. Buying at the top of the market in 1989, we resold ten years and many improvements later at the same price. But since 2002, it has been a stretch of rising prices. The vast sums people cough up for their Litchfield County real estate is general knowledge with all transactions, including names, listed in the local newspaper, along with fender-benders, bad checks, domestic disputes, and “doo-eys,” the vernacular for DUI and DWI citations.

The newspaper's police blotter is innocuous most of the time. A famous actress long-residing in Salisbury once read excerpts from it on

The David Letterman Show

to prove she's a country girl. But the threat of finding one's self on the “who did what” list keeps most of us honest and law-abiding, though it is off-putting when a friend's escapades end up in print. Do you mention it amidst small talk at the deli counter or pretend you didn't see it, unlikely as that may be with our slender newspaper? In a small town, the fact that everyone knows everyone else's business ups the ante. Likewise, property ownership and transfer is the local spectator sport, and full-timers and weekenders alike indulge for the fun of it, but also to reassure themselves about the value of their sizable investments.

The David Letterman Show

to prove she's a country girl. But the threat of finding one's self on the “who did what” list keeps most of us honest and law-abiding, though it is off-putting when a friend's escapades end up in print. Do you mention it amidst small talk at the deli counter or pretend you didn't see it, unlikely as that may be with our slender newspaper? In a small town, the fact that everyone knows everyone else's business ups the ante. Likewise, property ownership and transfer is the local spectator sport, and full-timers and weekenders alike indulge for the fun of it, but also to reassure themselves about the value of their sizable investments.

But the gossip around town served us well in one respect: everyone had a friend we should talk to about running a horse business. Kissing a few frogs would be worth the free advice. Our neighbor John Bottass called immediately with a recommendation. Grateful that we took on El-Arabia, he might also have felt he owed me for saving his cows. Riding my bike last fall, I capped the hill at Shady Maple Farm, enjoying the long descent only to cruise into dozens of cows, fretting in the road and skewing every which way into the woods. I u-turned and pedaled hard back over the hill to sound the alert. John jumped in his truck, and his

son Danny ran down the road to rustle up all that had now mysteriously disappeared. John kept driving, thinking his cows had followed the road, but on foot Danny and I spied a few confused heifers in the woods. Sounding a bell and banging a feed bucket, Danny coaxed about twenty of the worried from all directions. Seeing Danny lead a herd of relieved bovines up the middle of the road to the safety of home was reward enough. Danny and John knew each animal individually and accounted for all MIAs. While I could not imagine doing otherwise, John painted me the hero, believing that most people would not take the time to save a few tons of beef.

son Danny ran down the road to rustle up all that had now mysteriously disappeared. John kept driving, thinking his cows had followed the road, but on foot Danny and I spied a few confused heifers in the woods. Sounding a bell and banging a feed bucket, Danny coaxed about twenty of the worried from all directions. Seeing Danny lead a herd of relieved bovines up the middle of the road to the safety of home was reward enough. Danny and John knew each animal individually and accounted for all MIAs. While I could not imagine doing otherwise, John painted me the hero, believing that most people would not take the time to save a few tons of beef.

Other books

Jagged by Kristen Ashley

Awakening by Ella Price

Kiss of an Angel by Janelle Denison

Wings of Lomay by Walls, Devri

The Train of Small Mercies by David Rowell

Katie and the Mustang, Book 4 by Kathleen Duey

Forever in Love (Montana Brides) by Leeanna Morgan

Rescued by the Bad Boy (Bad Boys on Holiday Book 4) by Sylvia Pierce

Wild Rain by Christine Feehan

Death of a Bore by Beaton, M.C.