Hostage (3 page)

Tully’s Story

I’m not sure how I got in the car. One minute I was standing outside of it and then I was in, so I put my seatbelt on. I wasn’t thinking, you know, so my body was just doing stuff by itself. Breathe in breathe out. That seemed to be working. Put your seatbelt on because that was the law, and I didn’t want to break the law. The car screeched—it actually screeched like in the movies—and that was when I thought, ‘I don’t want to be here’ and tried to open the door but it didn’t budge.

We didn’t get too far up the street before we had to stop for a tram. You never see that in the movies. My driver was banging his hand on the steering wheel.

‘Jesus,’ he kept saying. ‘Jesus, Jesus, Jesus Christ.’

The tram had stopped to let some passengers off. There were cars parked on the side of the road so there was no room for us to squeeze through. I tried the door handle again.

‘Let me out,’ I said eventually. ‘Can you just let me out—’

‘Shut up,’ he said.

The tram finally moved off and my driver had stopped thumping the wheel.

‘Let me out,’ I insisted.

I looked out the back window. I had visions of Helene running after us with a pair of manicure scissors. Or the Chinese lady charging us with her jeep. But no one from the chemist was following us. A cop car passed us but it was going in the opposite direction.

‘Hey!’ I yelled.

I rattled the door handle as we took a right turn up a side street. The electronic window button didn’t seem to be working.

‘Here,’ I said. ‘Here’s good for me.’

He looked at me. ‘I’m not a taxi driver.’

We turned left then right again up a one-way street. The wrong way. He gunned the engine and we hit a dip with a thump that compacted my spine so I felt about a metre shorter.

‘Hey!’

He ignored me as he pulled out onto Brunswick Street, barely missing a pod of cyclists. We roared up another block before stopping for a pedestrian crossing. Seemed he had a soft spot for pedestrians, or maybe he just stopped out of habit. An old guy crossing the road was taking his time, pushing his jeep and muttering away to himself. His grey hair was pulled back in a ponytail, his coat ragged at the cuffs. He glared at us when he got halfway across and shook his fist.

‘Jesus.’

The cyclists sped past us and one kicked my door in payback before weaving a path around the dero. I banged on the window.

‘Please. Hey, please help me.’

Only the dero paid attention. He held my gaze as he reached the other side of the road.

‘Help me,’ I yelled, as we passed the cyclists again. We sped past them so fast that the lead cyclist wobbled in our wake.

Then we pulled out onto Victoria Street. And I closed my eyes.

Fitzroy Police Station: 25 December, 1.58a.m.

‘Wait.’ The Officer checked his notes. ‘So did you or did you not know this boy?’

Tully nodded and shifted in her seat. ‘I told you. I’d seen him ... around. I know him from school, but I didn’t

know

know him.’

‘Can you tell me his name?’

‘But I already told you before. When we first came in—’

‘Just for the record.’

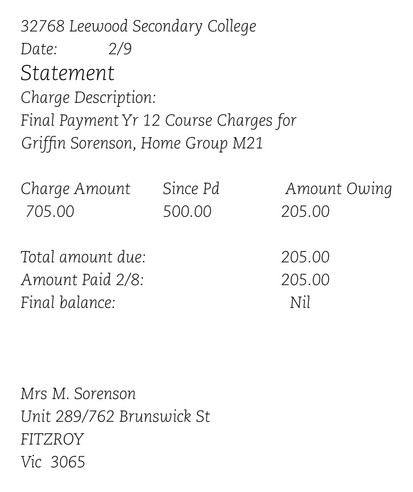

‘His name is Griffin. Griffin Sorenson.’

‘Then please refer to him by his name. It makes things easier.’ The officer nodded towards the tape machine. ‘So you didn’t try to get out of the car at this stage?’

‘I couldn’t open the door. Like I said.’

‘So he dragged you to the car, locked you in and drove off?’

The girl nodded, licking her lips. ‘Can I get, like, a drink or something?’

‘Did you try to elicit help?’ the officer continued.

‘What?’

‘Did you try to attract attention? Bang on the car windows? Scream?’

‘Yes. Of course. I told you. No one took any notice. Except maybe a dero and he couldn’t do anything.’

‘So you have a witness—’

The girl laughed. ‘You’re kidding, right? A dero. They all look the same. Even if we found him, he’s not gonna remember.’

Tully felt her aunt shift beside her. It felt like a warning.

‘So you drove around the city for an hour, banging on the car windows, screaming for help, and no one took any notice?’

The girl nodded. ‘It’s the city. What do you expect?’

‘And what did your abductor do?’

‘Do?’

‘While you were trying to attract attention.’

‘He ... I don’t know ... he drove.’

‘Did he threaten you with bodily harm? Did he strike you? Drive in a dangerous manner?’

‘No ... I don’t know ... can I get a Coke?’

‘Tully, I need you to concentrate—’

‘I’m thirsty. Please?’

‘I am sure we can arrange something. Could you please continue?’

Image 1

Image 1

Tully’s Story

‘Hey, where are you taking me?’ I asked him.

He didn’t answer.

It’s not like I was expecting him to. I was just making small talk while I tried to work out what kind of mood he was in. And I was wondering if I could kick my way through the windscreen, but that only worked in movies. The glass looked really solid and had some kind of tinting to keep the sun out. And prying eyes. I thought about my phone that was charging at home next to the microwave. I was supposed to keep it with me at all times. Bamps’s rules.

‘Where?’ I tried again.

He shrugged.

‘Dumb,’ I muttered.

‘What?’

‘Dumb,’ I said louder. ‘You’re dumb. This is so dumb. Why don’t you let me go—’

‘Shut up,’ he said.

He was looking kinda jittery and I figured he was starting to get the jumps from not having his medication. I’d seen that happen before.

I looked around for some paper—a parking ticket, anything to write on. I was thinking I could write a note for help and hold it up to my window without him seeing. Somehow. The car was clean. Laney’s car always has lipstick tubes and parking receipts and used tissues lying on the floor. Bamps doesn’t have a car and Mum’s cars are always halfway to the wrecker. They are more like a mobile home, filled with photos and clothes and suitcases and anything Mum can’t bear to live without. But this car ... this car was clean. It even smelled clean. I made a list of things I could use. An empty gum wrapper. Check. Three one dollar coins. Maybe I could trick him into swallowing them and while he was choking I could climb over him and get out.

Or not.

One plastic drink bottle—empty. Maybe I could break the bottle and slash at him with the jagged plastic.

Unlikely.

I wondered if I could fog up my window and write a backwards message to whoever pulled up next to us in the traffic. I spent time thinking about writing the letter ‘e’ backwards.

‘Where are we going?’ I asked.

He was a good driver. The traffic wasn’t too bad considering it was Christmas Eve, although it

was

still early. When someone pulled out in front of us, he just ducked to the left and moved out of the way.

‘You don’t have a plan, do you? I don’t think you know where you’re going,’ I said.

It was just a guess, but it hit a bullseye. He stared ahead without talking but the muscles in his face bunched up like he might be turning into the Incredible Hulk or something.

‘Why ... don’t ... you ... just ... shut up!’ he growled.

‘I’ve gotta take a pee,’ I said, jiggling my legs. The funny thing was I hadn’t needed to until I said so.

He didn’t say anything. Just turned his indicator on and pushed the sun visor down.

‘Are we going on the freeway?’ I was looking at the signs trying to work out where we were. ‘Cause, like, there are no toilet stops on the freeway. And I really need to go.’

He reached down to my feet and I pulled them up on the seat out of his way. Instead of grabbing at me, though, he picked up the empty drink bottle and threw it at me.

‘Can you aim?’ he asked.

Then the lights changed and we turned onto the freeway. I wanted to ask him to take me home, but for just that instant I couldn’t think where home was.

We moved around a lot, me and Mum.

Sometimes we had to move in a hurry, late at night or so early in the morning that it was still dark. Sometimes it was because we couldn’t make the rent money and other times ... well there was always a reason. She used to make a game of it. One suitcase each was all we could take. My suitcase was black with lots of red tape where the edges had come away near the zip. My memory tin fitted neatly into the front pocket.

‘We’re going, Pumpkin,’ was all she had to say.

I hated pumpkin. I hated any kind of vegetable, if it came down to it. Luckily Mum was more into takeaway food than home cooking.

I’d grab my suitcase from under my bed and shove it full of the things I loved. Sometimes she’d sing to show she wasn’t afraid. But I could tell. The way her voice wobbled on a high note or caught like there was something stuck in her throat.

‘Move it, Pumpkin,’ she’d urge.

There were things I had to leave behind that I dream about now and then.

My shiny red gum boots, only one week old.

A soft feather pillow that fitted my head just right.

A locket with my initials inside that I couldn’t find in our rush to leave.

I left Bronnie behind in Pakenham, my best friend at playgroup.

Connor’s last words to me were, ‘See you tomorrow.’ But I never did. I left him behind in Beaufort. I was six.

There were other kids I made friends with. Then I didn’t. If someone tried to be friends with me at school I’d tell them I was dying and that it was contagious. I told one girl I was a vampire and would probably suck her life-force if she got too close to me. They learned to stay away. I learned not to care.

Mum used to say it was better not to let anyone get close.

‘People let you down, Pumpkin,’ she’d say. ‘They may not mean to, but they will anyway.’

I didn’t realise she meant she would too.

Fitzroy Police Station: 25 December, 2.10a.m.

‘So you’ve moved around a lot?’ said Officer Fraser.

Tully figured he must have been playing the good cop, although even the woman hadn’t been too bad. She nodded.

‘That must have been difficult for you.’

Tully shrugged. ‘Yeah, boo hoo for me. Like I said, I got used to it.’

‘Did you make many friends at your last school, Tully?’

Tully gave a bark of laughter. ‘That school? You have got to be joking. I mean, I’d have to be desperate.’

‘So, no close friends at all?’

‘I don’t need friends. When can I go home?’

‘Have you ever been in trouble with the law, Tully?’

‘No.’

The officer nodded and wrote a note on his pad, then flicked back a few pages.

‘Do you know a Ms...’ The officer squinted at the rough handwriting, then grunted. ‘Ms Bukor?’

Tully shook her head.

‘Ms Helene Bukor is a shop assistant at the pharmacy. She said you were quite a regular customer.’

‘Oh. Her. Sure. I know her.’

‘Ms Bukor mentioned she had suspected you of shoplifting on more than one occasion.’

‘And I suspect her of impersonating a human being. Maybe we were both wrong? I need to go to the loo.’

‘Could you tell me what happened to the bag after the hold up?’ The officer sat still, pen poised over his notepad.

‘The what?’

‘The drugs and money that were stolen from the pharmacy.’

Tully laughed then stopped when no one joined in. ‘What are you talking about?’

‘As I stated at the beginning of the interview, we are investigating an armed robbery and abduction. At this point we are trying to ascertain the nature of the abduction.’

Tully felt her aunt lean in closer to her but this time she drew comfort from Laney’s presence. ‘I need to pee. Do you want to clean up the mess or can I go to the toilet?’

Tully’s Story

Have you ever stopped to think about toilets? Toilets and change rooms. I spend a lot of time in them so I guess you could say I am an expert. The smell of a girls’ change room is hard to describe. There’s musk and rose and vanilla. There’s baby talc and Nordic pine and cigarette smoke. And sweat. Lots of girly sweat. Stinky shoes. Damp towels and old socks.

People are pigs. They’re pigs. I know we have cleaners at the school—I’ve seen them cleaning up at the end of the day—but by the time I get to the change room the next day there’s always those little square bits of white paper on the wet floor. The liquid soap is empty because someone’s tried to write a message with it on the bench. The bin is overflowing onto the floor.

You can learn a lot about a person by what they do in the change rooms.

Rumours and secret meetings and birthday celebrations all take place in our gym change rooms. There’s this girl at school who does her best work in the change rooms. She is one of

those

people. The kind that smile while their eyes dart all over you looking for a place to stick the knife. I don’t mean a real knife. Worse than that. Her name is Ravel or Ramel or Camel—I’m never quite sure, so I try not to call her anything.

It was the last week before September holidays and after that there were only two weeks left of revision time before exams. I probably should have been in class but couldn’t stand the end-of-the-world theme the teachers had going for students like me who hadn’t done any work all year.

Ravel found me in the change rooms halfway through Period Two. The change rooms were filled with the bags of Year 8 PE girls and what looked like the Year 12 Outdoor Ed girls’ gear. So I wasn’t surprised to see Ravel rock up in her sports uniform. Her hair, pulled back in a messy golden ponytail, was bouncing even after she’d stopped nodding her head at me. She was a prancing Shetland pony. More like a pony than a camel. I wished I had a spare apple to shove in her mouth.

‘Hey, here you are,’ she said.

‘Yep,’ I agreed.

Ravel leaned against a wall and pulled her foot up behind her to stretch out her thigh. I knew that she wanted me to ask her what she’d been doing, so I didn’t.

‘I just wanted to explain about that thing at my house—at the start of Schoolies,’ she said finally.

‘Hmmm?’

‘It’s just a gathering,’ she said. ‘Just small. So, you know, maybe next time.’

‘I’m sorry...’ She was making no sense and I wanted her to leave.

‘The MySpace invite? I stuffed up. It wasn’t for everyone. My bad.’

‘Umm, sure Camel, whatever. You have fun.’

I saw her face in the mirror as I walked into a toilet cubicle. She looked confused.

‘I’d better get on with it,’ she said lamely.

‘Nice hair,’ I murmured as the door snapped behind me.

R, why don’t you answer my texts? Meet me in sports equip room at lunch. PLEASE. W.