Hottentot Venus (41 page)

I solved the problem of where the soul lies. It lies neither in the brain nor in the sex, neither in my lost hide nor in my bare skeleton. It resides, I believe, not in the here and now, nor in the future five hundred years from now, but in the past we have lost or forgotten or suppressed, ancestors whose voices repeat the litany of reincarnation beyond mere time.

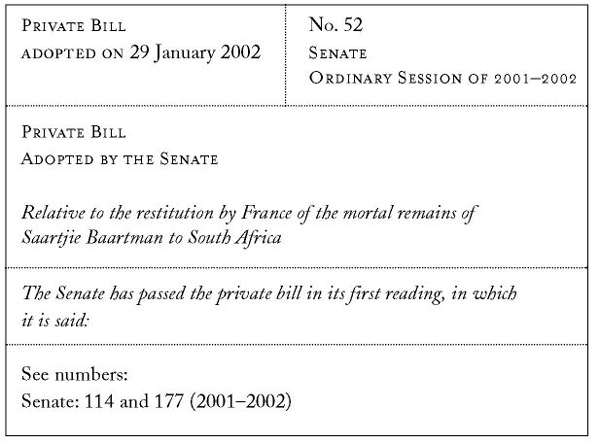

Which brings me to this moment. The moment when you have just turned this page and are wondering if such a sad and violent story could have a happy ending. How could it, you think to yourself. So let me tell you what it is. It was fitting that since my life seemed to be ruled by large groups of white men, deliberating my person in vast amphitheaters, their last discussion about me should have occurred in the National Assembly of France, January 29, 2002.

A tall Frenchman, who resembled Nicolas Tiedeman and spoke like the Reverend Wedderburn, and whose name was Nicolas About, rose to his feet in a still greater amphitheater, larger and more elaborate than the King’s Court, London, or the Jardin des Plantes’ comparative anatomy pavilion, before five hundred and thirty men and several women seated in circular, mounting rungs of dark oak and red velvet of the French Senate, and tried to put all my parts, all my bits and pieces, back together—that is, all my forests and jungles, my rivers and mountains, my deserts and grasslands, my orchids and

kanniedood

trees, my savage beasts and my migrating birds, my moons and my suns, my lion cubs and penguins, my wheat lands and coffee fields, my diamonds and gold, my Africa—and return them all to the state they were in before. He told this great assembly:

—It is high time that the mortal remains of Sarah Baartman, deprived of sepulture, can know at last the peace of a grave in her motherland of South Africa, freed of apartheid . . .

—The French Republic honors her memory. It is loyal to its convictions and its traditions. Loyal to its Declaration of 1789, which states that ignorance, neglect or disregard for the rights of man is the one and only cause of public wretchedness. Loyal to the Constitution of 1946, in which the French people proclaimed once more that every human being possesses inalienable rights regardless of race, creed or religion. Loyal to the law of 2001, which proclaimed chattel slavery a crime against humanity.

—If Sarah Baartman was the object of outrages, it was without doubt because she was black and a woman and because she was physically different. Attempts were made to make a monster out of her. But on which side is the monstrosity truly found? It has been argued as well that the Venus Hottentot has no legal status and that a law must be passed to remove her from the public domain. Well, just what is she? Are we talking about a simple object in a museum? Or are we talking about a human relic who needs special protection? Does France really own the Venus? Or are we merely her guardian? In no case is the storeroom of a museum a mausoleum worthy of a human being. If the Venus Hottentot has no legal status in France, let it be known that in the world and in South Africa, she is a relic and a symbol. A relic of the past, but a symbol of centuries of suffering under the yoke of apartheid and colonization . . . Sarah Baartman was born in 1789. What a symbol of our Revolution to restore the dignity of this woman two centuries after her death . . .

Oh what pretty words, what pretty words, I murmured.

—I hope that if we vote for the deacquisition of the Venus Hottentot from the collections of the Museum of Natural History, we can offer her a dignified burial in Africa.

(Applause)

—After having endured so many outrages, Sarah Baartman will at last emerge from the night of slavery, colonialism, racism, to recover the dignity of her origins and the soil of her people, to reclaim the justice and peace that has so long been denied her, argued Nicolas About. The French people proclaim once again that every human being, without distinction of race, religion, or creed, possesses sacred and inalienable rights.

(Applause)

—If there is no one else who demands to be heard, said the senator, the discussion is closed.

—We advance to a vote, said the president, standing at his podium, flanked by and gazing at the masters of the universe.

And so they did. Unanimously in my favor. A blinking board much like Master Cuvier’s blackboard floated high above the heads of the president and the senators. It held glowing red numbers like a regiment of fireflies.

Unique Article

From the date when the present law comes into effect, the mortal remains

of the person known as Saartjie Baartman cease to be part of the collectionsof the public establishment of the National Museum of Natural

History.

The administrative authority has, from the same date, a period of two

months to hand them over to the Republic of South Africa.

Conferred in public session, in Paris, on January 29, 2002.

The president,

Christian PONCELET

After that great debate, my bones left my glass cage feet first and were put in a simple pine coffin, covered with the flag of a free black South Africa. The Khoekhoe people had claimed me and demanded my return. The long night of the Dutch, the English and the Afrikaner was over. The sovereign people of South Africa had found their voice and a freed people had returned me to my home. I had become a raison d’état, and as such, I had had a whole amphitheater of Frenchmen once again debating my humanity.

And so they did. All my parts and pieces were gathered together pell-mell, my dreams and ambitions, my loves and hates, my sins and goodness, my innocence and guilt, my moon and stars, my biography became one . . .

I was emancipated at last, my brain and my sex placed beside me in a plain pine coffin, I traveled the long dark corridors from the basement parking at level C of the Trocadéro to the Esplanade, where I could see the lead-gray sky beyond the Eiffel Tower. A shiny white hearse sped me away, passing through the places I had lived in Paris: the rue St. Honoré, rue Neuve-des-Petits-Champs, the Cour des Fontaines, the Palais Royal, the Tuileries, the Place des Deux-Ecus, the rue du Pélican, the Impasse des Innocents, the Paris morgue, then north on the autoroute to Roissy and the South African jet that would take me home. The plane lifted, the great black-tipped wings of the purple heron bore me up and out, her long feathers hissing in the wind, her black-tipped beak pointed outwards, her long neck stretching endlessly in a horizontal line above the coast: like the final underline of a signature. The world unfurled below me like a scroll on which Africa was written. The plane descended. The door opened and the African sun burst through, carrying a dulcet scent of blossoms that perfumed my shroud.

Sweet laughter rose in my chest and found a home. They heard it.

As my coffin slid from the belly of the machine, amazed, I saw tens of thousands of colored people, more colored people than there was elephant grass on the plain, spread out in all directions as far as my eye could see. They rose as one to greet me.

—Mama Sarah! Mama Sarah, Mama Sarah, they shouted, and their voices richocheted across the plains, an ocean of sound.

I, Sarah Baartman, the dis-human, was now an icon for all humankind. The ten-thousand-voiced chorus of colored women bore my coffin aloft as it slid forward onto that sea of hands and shoulders carrying me to my final and only resting place. I found that my tearless skeleton could only weep.

The new South African police fought to control the crowd, which mutated into walls and bridges, canals and fences, trenches and barricades, trees, forests, rivers, elephant grass, tunnels beneath the lakes, dams, waterfalls, hills, to celebrate my return. My mortal remains were carried to where I could see the green and gold stripes of the Khoekhoe hills where our cattle had once grazed, where the Cape lion had once roared, where the sky had once burned and a thousand seasons had passed.

There in the moon of Broad Green, August 8, 2002, I burned on the beach where I had played with penguins and my mother had sung my birthday song. There I glided like the purple heron, surveying my funeral pyre, which glowed brighter and brighter as it receded into a pinpoint amongst the vast dunes, savannas, lakes, waterfalls, forests, orchards, orange groves, low clouds, deep springs, green pastures of my motherland, upon which the multitudes played, circling my embers like the loose waves of an ocean. My pyre was made of

kanniedood

tree branches, emblem of my immortality, of the People of the People. I was fired back into the embers and clay that had made me. My soul combusted, it soared, it rested, it sang, it was free.

An African breeze lifted my ashes and scattered them like wings upon the sea whose depths drank them. An extinct Cape lion, which was not extinct at all, came and sat beside me. Two penguins wobbled past the water’s edge, another heron pranced in the marshes. With a click of my tongue, I commanded a million women to rise up and bear witness to my agony by wearing red gloves in honor of Sarah Baartman. Then all was still.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following libraries and their staffs: the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; the library of the Musée de l’Homme, Paris; the library of the French Senate, Paris; the British Library, London; the Newspaper Library, London; the British Museum, London; the Albert and Victoria Museum, London; the Public Record Office, Chancery Lane, London; the University of Capetown Library, Capetown, South Africa; the New York Public Library, New York City. Thanks also to the following academics: Professor Willy Haacke, the University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia; Professor Jouni Maho, Göteborg University, Göteborg, Sweden; amateur French historian Laurent Goblot; and French journalist Gérard Badou. In the writing of this novel, I used many academic and scientific works, but I would especially like to acknowledge two: L’Invention

du Hottentot

by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar (CNRS, Université de Paris I, Sorbonne Publications), and Arthur Lovejoy’s

The Great Chain of

Being

(the William James lectures at Harvard University, 1933; Harvard University Press, 1942).

In chapter 18, the quotations of the fictive participants are verbatim, unadulterated nineteenth-century scientific writings on race, pell-mell from 1814 to about 1870. These include quotations from Jefferson, Lincoln, Hegel, Darwin, Beddie, Galton, Voltaire, Huxley, Knox, Morton, Drapper, Virey, Mandel, Broca, etc. In chapter 21, the dissection observations combine Cuvier’s Extrait d’observations with Anatomical Exami

nation

of a Bushwoman

by Professor H. von Luschka, A. Kock, and E. Görtz (

Anthropological Review,

London, 1870).

I would like to acknowledge Senator Nicolas About’s speech before the French Senate, part of which is reproduced here; my admirable agent, Sandra Dijkstra, and my editor, Deborah Futter, whose brilliance and tenacity made this book possible; the support of Elaine Brown; my secretary, Emanuelle Ruffet; my sons, David and Alexis Riboud, and especially my husband, Sergio Tosi, and the memory of my grandmother, Elizabeth Chase Saunders, steatopygia and all. I thank the former South African ambassador to Paris, Barbara Masakela, who read this manuscript, and the Khoekhoe activists and organizations who brought Sarah Baartman home.

As in a never-ending tragedy, the Musée de l’Homme in Paris no longer exists, having been itself dissected and eviscerated of its contents as an institution by government bureaucracy. I close this page with the words of Professor Fauvelle-Aymar: “From then on, the historic processes that rendered them invisible in the eyes of other men (their physical disappearance, ethnic mixing, encroachment of the frontier) are only the final touch that renders them useless in their eyes, less true than fiction . . .” May this fiction make them more than true.

And to conclude: Forgive the African debt, forgive the African debt, forgive the African debt.

BARBARA CHASE-RIBOUD

Hottentot Venus

Barbara Chase-Riboud is a Carl Sandburg Prize–winning poet and the prize-winning author of four acclaimed, widely translated historical novels, the bestselling

Sally Hemings

,

Valide: A

Novel of the Harem

,

Echo of Lions

(about the Amistad mutiny), and

The President’s Daughter

. She is a winner of the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize and received a knighthood in arts and letters from the French government in 1996. Chase-Riboud is also a renowned sculptor whose award-winning monuments grace lower Manhattan. She is a rare living artist honored with a personal exhibition, The Monument Drawings, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Born and raised in Philadelphia, of Canadian American descent, she is the recipient of numerous fellowships and honorary degrees. She divides her time among Paris, Rome, and the United States.