House of Hits: The Story of Houston's Gold Star/SugarHill Recording Studios (Brad and Michele Moore Roots Music) (7 page)

Authors: Roger Wood Andy Bradley

Tags: #0292719191, #University of Texas Press

2 0

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 20

1/26/10 1:12:10 PM

Under the Gold Star name, Quinn scored a major success with his premiere release. It came unexpectedly from an old song, the title of which Quinn had incorrectly documented as “Jole Blon” (#1314). That was his double misspelling of the French phrase “Jolie Blonde” (“Pretty Blonde”), the title of a traditional South Louisiana waltz lyric. The performer was Harry Choates (1922–1951), whose surname was also misspelled on the fi rst pressings of the disc label within the artist identifi cation “Harry Shoates & & His Fiddle” (yes, the ampersand was incoherently doubled too). A native of Vermilion Parish, Louisiana, Choates had grown up across the Sabine River in Port Arthur, Texas, a Cajun stronghold approximately ninety miles east of Houston. Accompanying himself on fi ddle and backed by a string band, Choates sang on his Gold Star debut disc with such plaintive enthusiasm that many listeners, whether they could translate the French lyrics or not, wanted their own copies of “Jole Blon.”

The result was a commercial success that twice in 1947 (January and March) hit the number four spot on the

Billboard

charts for “Most Played Juke Box Folk Records.” In so doing it also signaled the arrival of Gold Star Records on the national music scene. That recording was the fi rst and only Cajun song ever to make

Billboard

’s Top Five in any category—hence, its long-standing reputation as “the Cajun national anthem.”

Initially, however, Gold Star’s “Jole Blon” was only a regional hit, which introduced a new problem for Quinn to solve. Triggered by heavy airplay on a Houston radio station, the sudden local demand for copies quickly over-stressed Quinn’s capacity to make them in the little one-man pressing plant he had recently set up. Assessing the desperate situation, he realized the need to press more discs faster and to deliver them for sale while the record was still popular. So, despite his inclination for working solo, Quinn wisely arranged a licensing agreement with Modern Records, an independent West Coast company that thereafter handled much of the pressing, national distribution, and promotion of this erstwhile Gold Star single.

The strategy worked, for thousands of people far beyond the upper Gulf Coast were soon buying “Jole Blon” or punching its number on jukeboxes.

It would later also be leased and reissued outright on other labels, including not only Modern (#20-511), but also Starday (#187), D Records (#1024), and Deluxe. Surely a novelty to many, this recording nonetheless established the beloved Cajun song as a country music standard. As Texas Country Music Hall of Fame member Johnny Bush (b. 1935) says,

When I was a young boy living in Kashmere Gardens [in northeast Houston], my parents played Harry Choates’ “Jole Blon” on our Victrola, and that was a

g o l d s t a r r e c o r d s

2 1

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 21

1/26/10 1:12:10 PM

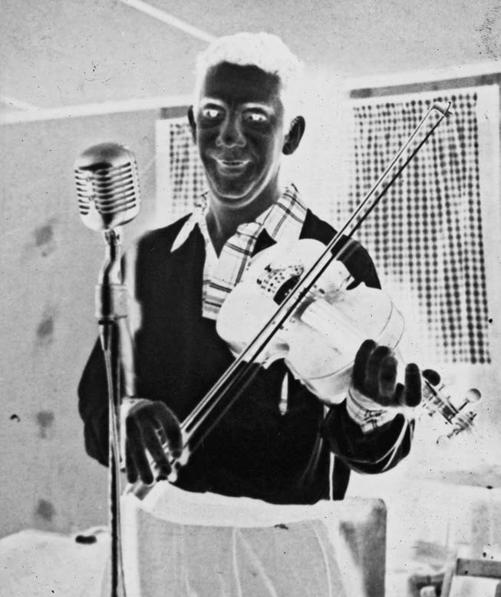

Harry Choates, Austin,

ca. 1950

giant smash hit in our area! It must still be a big hit today because if people come to your show and see fi ddles on the bandstand, you can’t leave without playing it at least once that night.

In search of similar hits, Quinn subsequently recorded Choates numerous times, singing in French and in English, before the latter’s untimely 1951 death. Some of the resulting tracks were issued on Quinn’s Gold Star label; others were recorded by Quinn but issued on labels such as Starday, Hummingbird, or D Records. Among those titles are several blatant attempts to capitalize on “Jole Blon,” including a version of the same song delivered in English, plus “Mari Jole Blon” (“Jole Blon’s Husband”), “Jole Blon’s Gone,”

2 2

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 22

1/26/10 1:12:10 PM

and “Jole Brun” (“Pretty Brunette”). However, none of these follow-up releases sold much, nor did any of the more than forty other Choates tracks that Quinn ultimately recorded.

Like his relatively short lifespan, Choates’s stint on the

Billboard

charts was brief; there would be no second act for him. There would be, however, other hits for Quinn and his record label. Though Choates was the man who fi rst put the “gold” in Gold Star, Quinn would have to discover other artists to achieve commercial success again.

one of the most influential singers and guitarists in postwar blues history, Texas native Sam “Lightnin’” Hopkins (1912–1982), had already made his fi rst recordings when Quinn met him and they began their uneasy professional affi

liation. In 1946 Hopkins had been recruited by Houston-based

talent scout Lola Anne Cullum (1903–1970) to travel to California, where, accompanied by pianist Wilson “Thunder” Smith, he cut a total of six tracks, his earliest, for the Los Angeles–based concern Aladdin Records. During his affi

liation with that label through early 1948, Hopkins recorded over forty songs, the majority of which were produced in sessions staged in rented studio space back in Houston. Quinn Recording Company was conveniently located in close proximity to the Third Ward, the southeast Houston neighborhood where Hopkins (who reputedly disliked traveling) resided for most of his life, and in 1947 Hopkins fi rst came there to record, yielding four tracks issued on Aladdin. Observing the interest of a West Coast company in this down-home local blues singer, Quinn seized the opportunity.

Hopkins soon was making records directly for Quinn and Gold Star. Their sporadic relationship continued through the demise of Quinn’s label in 1950.

During that span Hopkins recorded over one hundred songs at Quinn’s Telephone Road studio, reportedly usually at a fl at rate (for example, seventy-fi ve or one hundred dollars cash) per session.

Hopkins’s

fi rst Gold Star release (#3131) was a remake of a song previ-

ously recorded in California for Aladdin: “Short Haired Woman,” backed with “Big Mama Jump.” Almost immediately in demand on jukeboxes in the African American districts of metropolitan Houston, it became a bona fi de regional hit. Its success also prompted Quinn (who still used the now-misleading slogan “King of the Hillbillies” on the labels affi xed to his records)

to create a completely new category of Gold Star recordings, the 600 series.

It was devoted to blues music performed by black artists and intended for distribution primarily to black audiences—what was called the “race records”

market at the time. “Short Haired Woman” was thus the commercially successful follow-up to “Jole Blon” that Quinn had been seeking, and Hopkins was his dark-skinned new star.

g o l d s t a r r e c o r d s

2 3

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 23

1/26/10 1:12:10 PM

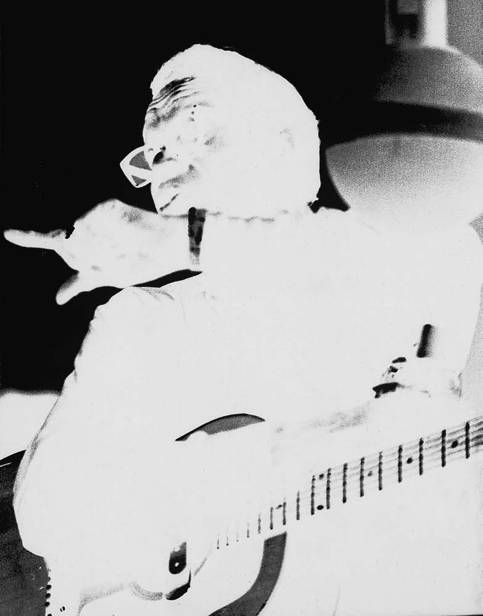

Lightnin’ Hopkins, inside Gold Star Studios, 1961

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 24

1/26/10 1:12:10 PM

Other Hopkins records produced by Quinn likewise garnered national attention on the

Billboard

R&B charts. For instance, in November 1948, “T-Model Blues” (Gold Star #662) peaked at number eight. Moreover, in February 1949, Hopkins’s performance of the poignant sharecropper’s protest song “Tim Moore’s Farm” (which Quinn had licensed to Modern Records) peaked at number thirteen. The many songs Hopkins cut for Quinn established his reputation as an innovator with wide appeal among black audiences. Those tracks, licensed and reissued on CD in 1990 by Arhoolie Records as

The Gold

Star Sessions, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2,

are today ranked by many afi cionados to be essential recordings by one of the greatest blues artists of all time.

Consider, for example, a

Paste

magazine article by Steve LaBate entitled

“Just for the Record: 10 Classic Sessions and the Studios That Shaped Them.”

Purporting to recognize “the greatest albums and singles . . . crafted in the polyphonic pantheons of the music industry,” it memorializes the sessions and studios that produced acclaimed masterpieces such as

Pet Sounds

by the Beach Boys (1966),

Abbey Road

by the Beatles (1969), “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye (1971), and

The Unforgettable Fire

by U2 (1984). Notably, only two recordings made before 1966 are commemorated, both from 1948: the Nashville session for “Lovesick Blues” by Hank Williams and the Houston session for “T-Model Blues” by Lightnin’ Hopkins. Though few Houstonians might have believed it at the time, Quinn’s modest Telephone Road studio was producing music that impacted popular culture at large—then and now.

Having occasionally harnessed Hopkins’s fertile, improvising genius was crucial for Gold Star Records. It was the payoff for the risks Quinn had taken in spontaneously producing a session whenever Hopkins dropped in, usually without advance notice, and off ered to record immediately for cash on the spot. As Chris Strachwitz explains in an interview:

Lightnin’ liked to make records, and no wonder, when he could sit down a few minutes, make up a number, and collect $100 in cash. And local record producer Bill Quinn had him doing just that. Whenever Lightnin’ needed some money, he would go over to . . . Gold Star Studios to “make some numbers.” And he had a fantastic talent to come up with an endless supply of these numbers. Many were based on traditional tunes he had heard in the past, but all of the songs received his personal treatment and they came out as very personal poetry.

Strachwitz had originally visited Houston in 1959 as a neophyte producer specifi cally hoping to meet and record Hopkins—a mission that would lead to the founding of Arhoolie Records, for which Hopkins eventually made numerous recordings. Consequently, the California-based Strachwitz developed

g o l d s t a r r e c o r d s

2 5

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 25

1/26/10 1:12:11 PM

a long friendship with both this iconic Texas bluesman and Quinn, whose facilities he sometimes rented and used over the years. Of the relationship between Hopkins and Quinn, Strachwitz says, “Just occasionally Lightnin’

would talk about Quinn, you know. He referred to Bill as ‘the right sucker’ [or]

he was ‘mister money bags.’ Of course, he appeared to call him these things in an aff ectionate way.”

Aff ection notwithstanding, the Hopkins-Quinn affi

liation was often

somewhat strained, particularly because the singer nonchalantly ignored previously signed Gold Star contracts whenever another opportunity arose to make a record with—and collect more cash from—someone else. As Alan Lee Haworth points out in

The Handbook of Texas Music,

ultimately “Hopkins recorded for nearly twenty diff erent labels.” Nevertheless, as Alan Govenar asserts in

Meeting the Blues,

the many tracks Quinn documented for Gold Star Records constitute Hopkins’s “fi nest work.” As such, those Hopkins recordings at Quinn’s studio are both aesthetically and historically signifi cant—and not exclusively in relation to the blues genre.

For instance, Hopkins’s Gold Star sessions yielded one track that signaled the incubation of a new genre of music along the upper Gulf Coast. The song titled “Zolo Go,” produced around 1949 or ’50 as the B-side to “Automobile”