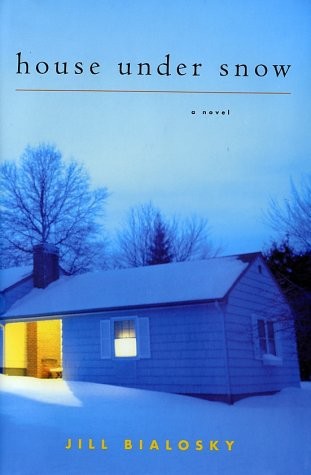

House Under Snow

Copyright © 2002 by Jill Bialosky

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Bialosky, Jill.

House under snow/Jill Bialosky.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN

0-15-100685-7

ISBN

0-15-602746-1 (pbk.)

1. Mothers and daughters—Fiction. 2. Paternal deprivation—Fiction. 3. Fathers—Death—Fiction. 4. Young women—Fiction. 5. Sisters—Fiction. 6. Ohio—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3552.I19 H68 2002

813'.54—dc21 2001007435

e

ISBN

978-0-544-59915-4

v1.1214

To my family

“Taint not thy mind, nor let thy soul contrive

Against thy mother aught. Leave her to heaven . . .”

House under Snow—F

ROM

H

AMLET

BY

W

ILLIAM

S

HAKESPEARE

The day my sister Ruthie left home, in 1973, my mother was upstairs in her bedroom in front of her vanity with a cutout of a model’s face from

Vogue

pinned to the oval-shaped mirror, experimenting with her eye makeup in an attempt to replicate the exact fusion of eye shadow, lipstick, and eyebrow shape. Our mother was obsessed with the curves, shadows, and cast of light across a face, the many moods the combinations evoked.

She had been this way most of our lives. And when she wasn’t preoccupied with her looks, she scoured the society pages of the

Plain Dealer

and

Jewish News

, to fish out the latest Cleveland society gossip—who had attended the art museum opening or the evening symphony—and what newly eligible men might be available. This was when she was still looking for a husband. She once had one of our relatives track down the phone number and address of a man she had dated in high school, after she read his wife’s obituary in the evening paper.

But on the night my sister left, my mother was still ensconced in her room tweezing her eyebrows and experimenting with lipsticks, even though her long and complicated history with men had dried up. It seemed to calm her, her endless fascination with mascara wands and nail lacquers; her

perpetual need for reinvention. It was the way she dealt with what she’d lost, a means of finding solace and safeguard from the tumult of the world outside herself. She was one of those women who believe that if her hair is the perfect shade, the ideal softness, she can control the chaos of her inner universe. That day, while my mother powdered and played with eye shadow and eyeliner pencils, Ruthie sequestered us in her bedroom for a conference.

“I can’t take her anymore,” Ruthie said. She had just turned sixteen that fall of 1973. She wore a winter scarf wrapped around her neck and a pale blue wool sweater that reflected her blue eyes. She had long, dark hair she parted in the middle, and white skin. A draft snaked through the house. Ruthie’s one Samsonite suitcase was already packed. “She drives me crazy.”

“I know,” I said.

Ruthie fingered the tassels on the curtain against her window. “It’s better if I’m out of her hair.”

“You don’t have to explain it.”

Even though I would miss Ruthie, part of me felt relief that she was leaving. It would mean that my mother would quit pacing the floors at night wondering when her daughter would come home. I was willing to tolerate Ruthie’s absence, if it meant her happiness. I knew my sister’s mind had gone to a thick and complicated place that had proved dangerous. Ruthie’s boyfriend, Jimmy Schuyler, had been busted for dealing pot. His parents sent him away to a boarding school in Pennsylvania. Then Ruthie had filled the hole left in her life by locking herself up in her room like a Buddhist monk in solitary confinement, and getting high.

“We’ll be fine,” Louise, the youngest of us three—we were each born barely a year apart—tried to reassure her. Louise was

tomboyish, with a short haircut framing her face, and knowing eyes that looked older than a girl of fourteen.

“I don’t want you to think I’m deserting you. If she gets weird you have to promise to call me. Maybe Aunt Rose will let you come, too.” Ruthie cracked her knuckles, pulling at each one of her fingers in a kind of perverse determination, a recent habit.

Unlike Ruthie, I couldn’t comprehend leaving my mother alone. I couldn’t imagine how our mother would survive without the armor of protection we provided. But later that night, after I heard the hired car come rolling into the driveway to take my mother’s firstborn, it dawned on me that Ruthie and I weren’t so different: Most of my waking hours, I realized, were concentrated on devising plots to escape the seclusion of our house.

When our mother watched the car move down the driveway, she pressed her nose against the window of the front door, a handkerchief balled up in her fist, and waved good-bye. The makeup she had spent hours working on had smeared. She stayed by the window long after the car had left its tire tracks behind. Her breath fogged up the pane, and she stood there on tiptoe, as if she expected the car to turn around and bring her daughter back. All that night I was kept awake by the sounds of my mother, Lilly, rummaging around in her bedroom, opening drawers, turning on the television, climbing up and down the stairs, restless as a sleepless child.

Ruthie’s absence that year was palpable. We felt it in the emptiness of her room without her dark silhouette against the window and her vacant chair shoved against the supper table. The atmosphere in the house was like a threatening cloud that promises precipitation but never erupts. Frozen snow from weeks

of chilling cold covered the ground and formed a layer over our roof, buried our shrubs, and blanketed the front stoop leading to the house. The wind caused the branches of the tree outside our window to thrash like someone waking from anesthesia.

Now I live hundreds of miles from my mother’s house in Chagrin Falls. Decades have passed since that one long winter. But the minute the snow begins to fall over the tall buildings of the city, everything comes back—the shudder the winter chill sends through the body, the reluctance to have your footprints be the first to taint the snowbound streets, the lack of separation between falling snow and sky, the sense that winter will never end. But what stays with me most is a feeling I carry of being

responsible

, as if by leaving home and creating a life for myself I abandoned my own child.

In a few months I will be coming home for my wedding. After all these years, I still have to steel myself. The thought of returning is bittersweet. Half of me wants to celebrate this occasion with my family, and the other half wishes we’d decided to run off and elope.

After I return to my apartment from work for the evening, I obsess over the details of the wedding, and then I think about how far I’ve come. I remember our house in winter—the endless white madness of the snow and the rush of cold air as it moved into the living room, circulated through our narrow rooms, blew the door shut behind it—as if to remind me how fragile happiness is, how easily it can shatter like a pane of glass. That’s why I’m compelled to tell this story—don’t we all have one secret that has shaped us we are burning to reveal?—to convince myself that I’m entitled to my own life.

We never forget childhood. It is always planted there like a white house on top of a steep hill. My memories are harsh but necessary. I imagine the wind, uncontrollable and crazy, coiling around the trees, whipping off branches, pushing cars off the road, and in one powerful gust setting in motion an unstoppable avalanche capable of destroying everything in sight.

In the long-awaited spring after the winter Ruthie left, the smell of lilac and forsythia overwhelmed. All the windows in the house were open. Children ran across our yards in cutoffs and T-shirts, suburban lawns glistened with promise. It was as if, because the winter had been long and bleak, God decided to bless us with a fruitful spring. In Ohio the trees are rich and bountiful, and sitting beneath a huge maple or elm waiting for a cool breeze to whip through the maze of leaves and branches to save us, we could barely make out the sky, wanted only to lift its mantle of heat.

That spring there was magic in the air. Often, in the distance, was the smell of rain and lightning, and the light roll of thunder. All it would have taken was an outstretched hand and warm lips to kill the heat. Or a bluebird to put out her wing and cast the spell over my body, and I’d sink onto soft grass, into arms and tangled legs, then be gone like a puff of smoke. And all that would be left was a boy’s aura, pungent, strong enough to bring tears.

The end-of-school parties began in April and lasted until late June. I was going into my senior year. The fact that Austin Cooper had invited Maria Murphy and me to

his

party was a sign we’d made the inner circle. On the night my relationship with Austin Cooper was sealed, the crowd was thick, making

the rooms of the house feel cramped; the air was layered with smoke and the dark haze of pent-up energy and recklessness.

Austin Cooper had

moved to Chagrin Falls from Denver, Colorado, three months before the party. He was tall with long, thin legs, broad shoulders, and a square-jawed face that made him look older than seventeen. The spaces underneath his cheekbones pulsed with intensity when he spoke. When I saw him walking down the halls of our school in his black work boots and faded jean jacket, and his eyes fastened on mine, it was as if a door had opened; there was no glass, no screen of protection. I walked into the open bloom of him and was trapped.

The rumor was that in Denver, Austin Cooper’s mother had screwed around with the husband of the family next door, and then after she’d taken off with him to another state, he dumped her. After the affair, Austin’s father, who was a partner in a national accounting firm, relocated to Cleveland in the middle of Austin’s senior year of high school. Austin was exactly the kind of boy I’d dreamed about. Catherine, the great and tragic heroine of

Wuthering Heights

, the book I had studied like a bible my junior year, said this of Heathcliff: “My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath—a source of little visible delight, but necessary.” The visceral persuasion Austin Cooper had over me was there from the moment I inhaled my first breath of him.

That first day, Maria was whispering the rumor about Austin Cooper’s parents when our math teacher, Mr. DeMott, was turned to the blackboard to write out the formula for finding the area of a right triangle. It was the first day after

spring break. Any time there was a new kid in our school it was cause for celebration. We looked forward to a new face to break up the monotony of our ordinary existence. That day Austin sat for a few minutes in the last row of Mr. DeMott’s classroom, having read his schedule incorrectly. Once he realized he was in the wrong classroom, he packed up his notebook and stack of books and left, but not before his eyes passed through mine.

When I saw Austin’s bowlegged walk move down the corridor after class, I dawdled near my locker as if I were looking for a misplaced book. He stopped, and his eyes ran along the length of my body, lingering over each curve. I had to catch my breath. After I turned my back, I felt his eyes again, the press of them, like a wind, on my neck.

He walked me home from school that day, and immediately he consumed my imagination, the way an overgrown cherry tree in blossom overtakes a yard. Then, a few weeks before his party, he invited me to his house after school. Austin had the house to himself each afternoon until six-thirty or seven o’clock at night, when his father came home from work. After he put a new Jefferson Starship album on the turntable, he caught me off guard and kissed me. My body went liquid to his touch. We went up to his bedroom and rubbed against each other, in our clothes, for so many hours that the skin on my legs was raw. The register of his hands on my skin felt like a tattoo grafted into my body. But after that late afternoon I still hadn’t been sure whether I meant something to Austin. I didn’t know how to gauge a boy’s interest. The invitation to his party I took as a good sign. That maybe we were going out.