How Hitler Could Have Won World War II (35 page)

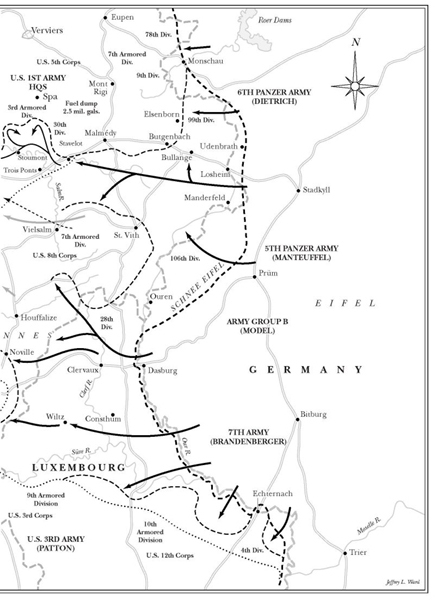

On the American side, the 5th Corps's 99th Infantry Division, a new but reliable force, covered the region from Monshau south to Losheim. There the 14th Cavalry Group, equipped mainly with light weapons, protected the “Losheim Gap” itselfâone of the few fairly open regions of the Ardennes, and thus the main avenue of approach.

To the south facing the West Wall and emplaced in the Schnee Eifel Mountains some five miles east of the Our River (the German-Luxembourg frontier) was the 8th Corps's green 106th Infantry Division, filled with ill-trained replacements assigned just before leaving the States.

Next came the 28th Infantry Division, a veteran outfit refitting after losing 5,000 men in the Hürtgen Forest. It held a twenty-five-mile sector along the Our to the Sûre River, about fifteen miles north of Luxembourg City.

Below the 28th Division, the 4th Infantry Division held twenty miles along the river (now called the Sauer) from Echternach to the Moselle River, then along the Moselle to a point twelve miles southeast of Luxembourg City. The 4th Division had suffered in the Hürtgen Forest almost as much as the 28th Division, and likewise was resting and refitting.

In 8th Corps reserve, Troy Middleton held the new 9th Armored Division, except Combat Command B, attached to 5th Corps's 2nd Infantry Division. In the whole corps area, Middleton had 242 medium Sherman tanks and 182 self-propelled (SP) guns or tank destroyers.

Much depended upon the advance of Sepp Dietrich's 6th Panzer Army with four SS panzer divisions. It was nearest the Meuse in the decisive sector.

When the attack burst across the front lines early on December 16, the U.S. 99th Infantry Division below Monschau successfully blocked Dietrich's right-hand or northern punch around Udenbrathâand thus stopped his shortest route to Antwerp. Dietrich's left-hand or southern punch broke through around Losheim, and was able to push westward over the next two days against tough American resistance around Butgenbach and Elsenborn. But the 99th Division's resistance denied the Germans the northern shoulder they had planned to seize, and provided a base to press against them later.

Meanwhile 1st SS Panzer Division drove forward in an effort to outflank Liège from the south. The leading column, a battle group under SS Lieutenant Colonel Joachim Peiper with a hundred tanks, pressed forward, aiming for the Meuse crossing at Huy. At Malmédy on the way, it gained ignominy by massacring eighty-six American prisoners, as well as a number of Belgian civilians.

Peiper's group halted just east of Stavelot on December 18, but didn't grab the bridges over the Amblève there. Peiper also didn't go for a huge supply dump just to the north with 2.5 million gallons of fuel, or for Spa, a few miles farther on, where Hodges's 1st Army headquarters was located. American reinforcements reached Stavelot during the night and blew the bridges over the Amblève in Peiper's face the next day.

Peiper tried to detour down the river valley but Americans checked him at Stoumont, about six miles farther on. Peiper now learned that he was well ahead of the rest of 6th Panzer Army.

On Manteuffel's 5th Panzer Army front the attack got a good start. Storm battalions infiltrated into the American front, opening the way for the tanks, which advanced at 4 P.M. on December 16 and pressed forward in the dark with the help of “artificial moonlight.”

Manteuffel's forces broke through in the Schnee Eifel against the 106th Infantry Division and 14th Cavalry Group. These forces covered the important road junction of St. Vith, some ten miles to the west. Two infantry divisions and a regiment of tanks of Walter Lucht's 66th Corps surrounded two regiments of the 106th and forced at least 8,000 men to surrender.

Farther south two panzer corps, Walter Krüger's 58th and Heinrich von Lüttwitz's 47th, attacked westward. The 58th crossed the Our River and drove to Houffalize, aiming at a crossing of the Meuse between Ardenne and Namur. The 47th was to capture the key road center of Bastogneâ where six roads came togetherâand drive on to the Meuse south of Namur.

Outposts of the U.S. 28th Division delayed but could not halt the Germans crossing the Our, and by the night of December 17 they were approaching Houffalize and Bastogneâand the north-south road between them, which the Germans needed to develop their westward sweep.

In the extreme south, the 5th Parachute Division of Brandenberger's 7th Army got to Wiltz, a dozen miles west of the Our, but the 28th Division's right wing gave ground slowly, and 9th Armored and 4th Infantry Divisions checked the advance after it had gone four miles. By December 19, the southern shoulder of the German attack was being held firmlyâand Patton's 3rd Army to the south would shortly be reinforcing it.

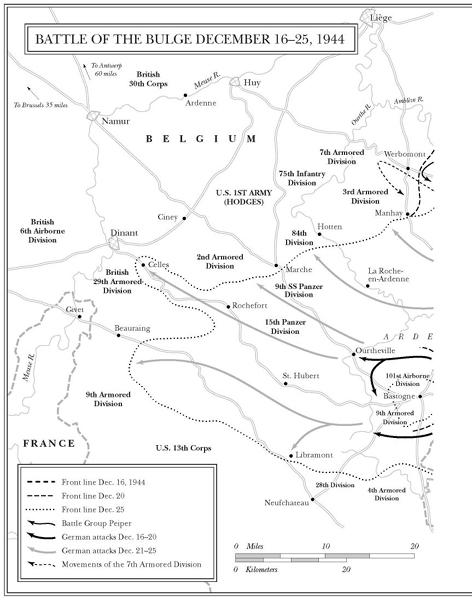

Meanwhile Manteuffel's pressure on St. Vith and Bastogne increased. The Germans made their first small attack on St. Vith on December 17. The next day the bulk of the U.S. 7th Armored Division arrived. Outlying villages fell to German assaults, while panzers outflanked St. Vith north and south.

By December 18, Lüttwitz's 47th Corps was closing on Bastogne with two armored divisions (2nd and Panzer Lehr), plus the 26th Volksgrenadier Division. But a combat command of the U.S. 9th Armored Division, plus engineers, had arrived to help defend the crossroads, and the 101st Airborne Division under Anthony C. McAuliffe reached Bastogne on the morning of December 19.

After the Germans were unable to rush the town against fierce defenses, the two panzer divisions swung around both sides of Bastogne, leaving the 26th Division with a tank group to reduce it. Thus Bastogne was cut off on December 20.

After finally realizing this was not just a small spoiling attack, Bradley ordered 10th Armored Division north and sent 7th Armored and 30th Infantry Divisions south. Thus, more than 60,000 fresh troops were moving, while 180,000 more were to be diverted over the next eight days.

The 30th Division struck Peiper's battle group, grabbed part of Stavelot, and, with the help of powerful blows by fighter-bombers, broke Peiper's links with the remainder of 6th Panzer Army. By December 19, Peiper, desperately short of fuel, found that the 82nd Airborne Division, plus some tanks, had arrived, turning the balance against him. The remainder of Dietrich's SS panzer forces were still stuck in the rear, with too few roadsâand these interdicted by Allied aircraftâto get forward.

Peiper's battle group began to retreat on December 24 on foot, abandoning its tanks and other vehicles.

To the south, the U.S. 3rd and 7th Armored Divisions had barred Manteuffel's advance westward from St. Vith, where a strong German attack finally drove out the Americans with heavy losses. But a huge traffic jam permitted remnants of the 106th and 7th Armored Divisions to get away, and hindered Manteuffel's advance toward the Meuse.

Two major factors slowed the German advance: mud and shortage of fuel. Only half the artillery could be brought forward due to fuel lack. Foggy weather had favored the Germans on the opening days by keeping Allied aircraft on the ground. But clear skies came back on December 23, and Allied fighters and bombers commenced a terrible pummeling of the German columns.

On December 20 Eisenhower placed Montgomery in charge of all Allied forces north of the Bulge, including the U.S. 1st and 9th Armies. Montgomery brought the British 30th Corps (four divisions) west of the Meuse to guard the bridges.

Gaining command of two American armies was a great coup for Montgomery and a blow to Bradley, not helped when Montgomery arrived at 1st Army headquarters, as one British officer reported, “like Christ come to cleanse the temple.” He made things worse at a press conference where he implied that his personal “handling” of the battle had saved the Americans from collapse, when actually he had done practically nothing. Montgomery also spoke of employing the “whole available power” of the British armiesâa palpable lie heightened by the fact that he insisted he must “tidy up” the position first, and did not strike from the north until January 3. All the while 3rd Army was counterattacking toward Bastogneâspearheaded by the 4th Armored Division, following Patton's order to “drive like hell.”

The 4th Armored, supported by the 26th and 80th Infantry Divisions, collided with the German 5th Parachute Division on the main north-south road. The paratroops had to be driven out of every village and block of woods. However, reconnaissance found there was less opposition on the Neufchâteau-Bastogne road leading northeast, and on December 25 Patton shifted the main attack to this line.

In Bastogne the situation remained critical. Repeated German attacks forced the Americans back, but never overwhelmed them. When Lüttwitz sent a “white flag” party on December 22 calling on the garrison to surrender, General McAuliffe replied: “Nuts!” Subordinate officers, seeing the baffled looks on the Germans' faces, translated it as “Go to hell!”

The next day better weather permitted Allied aircraft to drop supplies to the beleaguered troops. On Christmas Day the Germans made an all-out effort, but failed. Meanwhile the 4th Armored Division fought its way into the town at 4:45 P.M. on December 26. The siege was lifted.

A thin finger of Manteuffel's advance got within four miles of the Meuse, five miles east of Dinant at Celles, on December 24. But that was the high-water mark. The British 30th Corps had moved onto the east bank of the Meuse around Givet and Dinant, and fresh American forces were coming up to help.

Hitler had recognized his hope of capturing Antwerp was an illusion, and had shifted his goal to seizing crossings of the Meuse, releasing the 9th Panzer and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions from reserve to help Manteuffel clear the approaches to Dinant between Celles and Marche. But the panzers were being severely harassed from the air, and after December 26 none could move during the day.

Meanwhile Lawton Collins's U.S. 7th Corps was converging on the threat. Collins had the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions and the 75th and 84th Infantry Divisions, and they slowly gained ground. On Christmas morning they recaptured Celles. The 9th Panzer Division arrived near the village on Christmas evening but could not shake the 2nd Armored Division in front of it.

Sepp Dietrich's 6th Panzer Army to the north tried to assist Manteuffel, but his panzer divisions made little impression on American defenses that now were strongly reinforced, with swarms of fighter-bombers on momentary call to strike anything moving.

Manteuffel wrote that his reserves were at a standstill for lack of fuel just when they were needed.

Hitler wanted to hold the positions in the Bulge, and insisted that Manteuffel capture Bastogne by cutting Patton's Neufchâteau-Bastogne corridor. But German attacks over three days, beginning December 30, failed.

It was obvious to Manteuffel that he could not hold the Bulge without Bastogne and could do nothing against Collins's determined advance on the west. He telephoned Jodl and announced he was moving his forces out of the nose of the salient. But Hitler, as usual, forbade any step back. Instead, he ordered another attack on Bastogne.

To demonstrate how determined he was to have Bastogne, Hitler risked what was left of the Luftwaffe to prevent Allied fighter-bombers from intervening in Manteuffel's efforts. Early on New Year's Day a thousand Focke-Wulf 190 and Messerschmitt 109 fighters came in at rooftop level over twenty-seven Allied airfields in Holland, Belgium, and northeastern France. The Germans destroyed 156 planes, 36 of them American, most of them on the ground or while trying to take off. These were heavy losses, but the Allies could replace them quickly. The Luftwaffe, however, lost 300 planes and as many irreplaceable pilots, the German air force's largest single-day loss in the war. It was the Luftwaffe's death blow.

Having failed to cut the corridor south of Bastogne, Manteuffel now struck from the north astride the Houffalize-Bastogne road, using four depleted and exhausted divisions which, between them, had only fifty-five tanks. The Germans got nowhere, just as Manteuffel had feared. He now pulled the forces off. The threat to Bastogne ended.