How I Became a Famous Novelist (14 page)

Read How I Became a Famous Novelist Online

Authors: Steve Hely

“Uh, thank you.”

“But what do I know? I’m a Jewish kid from Scarsdale.”

Just then a Sasquatch tapped David on the shoulder. That may sound like an exaggeration—it is not. This guy’s face was hidden with matted, untended hair and the air around him seemed to quiver from his body stink, like heat rising from a desert highway. He smelled like the most poorly tended organic farm in the world.

David said “hey!” and they shook hands.

“How’s it all going, with the thing?”

“Oh, it’s pretty good. Getting pretty sick of chicken!”

“I bet.”

“And my dentist, he’s not too happy.”

“Oh yeah.”

“But all in all.”

“Cool, man,” said David. “Shoot me an e-mail sometime, bring me up to speed.”

“Can’t, man, remember? No computers.”

“Oh right, right.”

The Sasquatch left.

“That guy,” said David, “has some nuts on him. He kept pitching me these books—he’d go for a year only eating fried chicken. A year of only drinking soda. A year of never showering, no computers, all these ideas. I could never sell them individually. But then finally he came up with the idea of doing them all at once. Sold it, he’s off and running.”

David took a big sip of beer. “Dude’s having a rough year. Anyway—your book! Lucy, she’s good. I’m gonna get her to clean a lot of it up.”

I could see objections forming behind Lucy’s eyes, but she stayed quiet.

“She’s gonna cut a lot of the crap out. But—it’s good. People will buy it. I think.”

Another pause. David looked up at the bar, then stood up.

“All right.” He shook my hand.

We walked outside, the three of us. As we neared the subway, David told us to follow him, and he started off down a side street. Lucy and I looked at each other and followed, and he led us down a slope to a small square of park. On one side was a row of three-story brownstones.

“You see that place?” David pointed at the one on the corner, which stretched back for nearly a block. “That’s Josh Holt Cready’s place. Three point five million dollars.

Manassas

paid for that place.” Then he turned, and locked me with his eyes. “I passed on that book! Fuck!” We gazed at the place for a minute.

Then David yelled “You suck, Cready!” We all ducked behind a bush. We waited for maybe ten seconds, then peeked our heads over the top. No reaction from Cready’s house.

Then a light came on upstairs. We all freaked out and booked down the street.

“Shattered my confidence,” David said, as we scurried away. “Confidence! That’s the one thing you need to be an editor! Never again, I swore to myself.”

We got to the subway. David shook my hand. “All right. Good stuff. I’m gonna see if I can make this happen. Don’t fuck me on this.”

And he walked off. Lucy was holding her head in her hands.

“Um, is he okay?”

“Oh no.” She took her hands away. “But I think you just sold your book.”

10

The Roman Empire. For two millennia, it’s stood as the symbol of value. Of virtue. Of integrity. Of lasting strength.

Our very word—investment—is derived from Latin. It means the same things today that it did two thousand years ago. Security. Stability. Your financial future.

At Via Appia Funds, we combine the values of ancient Rome with a forward-looking 21st-century approach to investment. Our goal is simple: to build an epic empire of wealth for all our clients.

When you invest with us, you’ll feel the strength, the confidence that comes from turning your future over to dedicated, devoted professionals who can respond to your needs. Professionals who can adapt to an ever-changing marketplace, while always staying true to the core principles that last beyond years.

Choose Via Appia Funds. Choose integrity. Choose strength. And choose a financial future that will stand, proud and sturdy as the Coliseum.

—excerpt from an introductory letter for Via Appia Funds by Pete Tarslaw

What I assumed would happen after I sold my novel

Some editors would take me to someplace that made cocktails with elderberries. I’d get drunk and hold forth. As I left I’d see a model on the street waiting for a cab.

“Can you only write, Pete Tarslaw, or can you flag a cab as well?”

“I can flag a cab.”

“Then let’s go.”

Back in her apartment, in Gramercy or somewhere, wherever models live, she would press her lips against my ear.

“I know you can write love beautifully, Pete Tarslaw. Can you make love beautifully as well?”

“Why don’t I show you?” I would do so.

Two months later: at a dinner in London (I’d be in London for the UK launch of

T. A. C.,

and the restaurant would be called something like the Fatted Calf), Zadie Smith would lean across the table to me.

“You know, I’m on to you, you bastard.” Then she’d smile. “Takes one to know one. I won’t tell on you if you don’t tell on me.” Later the two of us would do coke off a manuscript.

Also I would be on Charlie Rose.

What Actually Happened After I Sold My Novel

When I saw my contract I learned why writers dwell on hard-luck characters who fix busted boilers and squabble over grocery bills. It’s because writers don’t get paid very much. Ortolan offered me $15,000 for

The Tornado Ashes Club

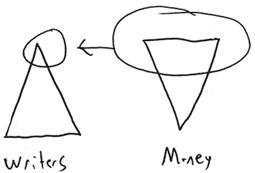

. Most of that I wouldn’t see until the book came out. Lucy drew a graphic that explained the finances of the publishing game:

The few writers at the top, the Tim Drews and Pamela McLaughlins, take all the money. There’s not much left for the lots of writers at the bottom.

My book was set to come out in early November. David Borer told me that the British owners of Ortolan believed that Americans did a lot of reading over Thanksgiving, “They buy books to take with them on the train to Cleveland and so on” was their logic. With layoffs looming no one was brave enough to tell them otherwise.

* * *

Once, in ninth grade, I made a model of the Eiffel Tower out of toothpicks for a big project at school. When I finished the whole thing was lopsided and warped, but it was so fragile that I dared not tamper with it, I just hoped it would stay together long enough for me to get a grade.

That’s how I felt about

The Tornado Ashes Club

. Lucy spent the summer editing my manuscript, while I watched Red Sox games in my underwear, indifferent to the outcome. She’d e-mail me a question almost every day. “How did Luke learn Spanish?” “Why doesn’t Silas just explain to the police that he didn’t kill his boss?” “Does a dying deer really smell

faintly of cinnamon

?” “You use the word

sallow

four times, and I’m not sure you ever use it right.” She seemed to be catching on to the slapdash nature of my work: “On page 41 you say that Albuquerque is ‘a hot, blast furnace of a city,’ but then eight pages later you say that ‘mountain breezes kept it cool as a treehouse in October.’ ”

Finally I had to tell her she should just do whatever was necessary and stop bothering me with it.

I had nightmares where I saw copies of

The Tornado Ashes Club

staring up at me from the remainders table, crowded next to other rejects, their covers pathetically desperate, like the faces of misshapen girls at a middle school dance. The image haunted my afternoon naps. It was amazing how quickly my swagger had turned to cowardice.

Then, in June, I got a call from Jon Sturges. When he called I was taking a bath, which is an inexpensive way of eating up time. He started telling a story about how high-born Roman women paid extravagant sums to sleep with famous gladiators, which was interesting but not relevant to anything.

“So, I’m expanding on a new frontier. Really pushing aggressively.”

“Right on.”

In fairness to what would eventually transpire, I’ll note that in his description of his new business plan, Sturges used lots of terms like “malleable” and “freely structured.” So I should’ve realized he hadn’t done the legal legwork. But what he described sounded to me like the kind of low-level, you-don’t-get-caught sort of illegal.

The job he offered me was writing out some sales materials for a mutual fund he had founded. He claimed he had a long list of “serious investors” who were already involved.

“See, I’m great at picking companies, you know? I just have a talent for it. But I can’t always—you know—articulate their strengths in written form. That’s your talent, bro.”

“Right.”

“So, I’ll send you some—you know—basics, and you write it up. Rome—that’s the theme. The strength of—you know— Rome.”

“I think I can do that.”

“We’re really dynamically shifting the way capital is gonna flow, Pete. It’s a fully integrated system. But we need somebody with your kind of focused clarity.”

“How much will you pay me?”

“A thousand dollars.”

“Okay.”

I should stress here that I didn’t know what happened to my writing when I was done with it. I assumed it ended up in some kind of newsletter I never saw.

The truth is, I just didn’t worry about it. On the Web site there were stock pictures of Roman ruins and a place to type in your credit card info. I’d work for one hour every day during the 11

A.M.

airing of

The Price Is Right.

Most of that summer I spent on the couch.

In August, Lucy sent me a mock-up cover design: a tornado that looked like it’d been done in fingerpaint against a green field. The font was simple and all-American, like on an IHOP menu.

11

It’s long been my contention that the most influential man in the history of American fiction was Henry Ford. Ever since the first Model T rolled off the production line, narratives of road trips have been a mainstay of popular literature. One imagines all the drivers of American fiction of the past fifty years on the same freeway. They’d form a traffic jam as congested as downtown Los Angeles at 5:45

P.M.

, with Sal Paradise leaning on the horn.

Unfortunately, not all authors who take to the road are Homers and Kerouacs, nor is every meandering journey an odyssey. Consider

The Tornado Ashes Club,

the debut novel of one Pete Tarslaw. Beginning with a gunshot in Las Vegas, Tarslaw launches his characters on a dizzying zigzag trip across time and space that leaves one reaching for the car-sick bag. The convoluted plot is rife with all manner of roadside oddities: French peasants, high school football, blossoming love. But it’s much like a Las Vegas buffet: everything’s there, but none of it’s very good. Tarslaw’s prose seems to never catch its breath. He squanders the reader’s patience by rendering every loose hubcab and half-eaten cheeseburger into a listless rhetorical faux-exuberance, all of it weakly undergirded with a primer of vague Christian metaphor. With a slurry of mixed images and tiresome characters, in language as worn out and withered as the sixty-some-odd bar slattern nursing a cigarette and a whiskey sour at a cheap casino, his is a road trip that makes you wish you’d taken the plane.

—excerpt from Charles Meredith’s “Of Books” column in the

San Francisco Chronicle,

December 1, 2007

There’s a neat book called

Panned!: Bad Reviews of Great Works

. It’s made up of excerpts from contemporary reviews that completely missed the point. Slams of books, music, art, and movies we now recognize as genius. Like

Huckleberry Finn:

“Mr. Samuel Clemens, who styles himself ‘Mark Twain,’ has penned a riparian folly which, in its vulgarity and crude language, does discredit to himself as well as to the Negro race, the intended beneficiary of these strained efforts.” And

The Great Gatsby:

“One hopes Fitzgerald, whose lamplight burned so brightly in

This Side of Paradise,

can recover from this misstep. For beneath the jaundiced view of American enterprise and the juvenile obsession with the cocktail-and-party set, we sense the hand of a competent writer of romantic fiction.”

Maybe the best one is of

Moby-Dick:

“It is best read as a lesson in the inevitable failure of a writer of no Ambition. Mr. Melville wastes his labours. He chooses no grand theme, nor bothers much with the human condition, save a few comic sketches of the mad captain. Instead he bores the Public with a chronicle of whale-fishing, accounts of which are already numerous. Those wishing for an education in cetology will prefer Mayhew’s

Whales of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

”

There’s a final chapter, too, made up of wildly positive reviews of now-forgotten works: “

Odeon Unbound

is that rarest of things, a novel in which greatness can be perceived in

every sentence. It is our firm prediction that alongside Shakespeare and Dr. Johnson, our children will study the works of Gilbert Pentweed, and his name will be etched in the ranks of literary immortals.”

Aunt Evelyn sent me a copy of

Panned!

along with a batch of maple cookies. Her accompanying note was full of “buck up” platitudes. She was of course too polite to mention Charles Meredith’s review.

I try not to hate anybody. “Hate is a four-letter word,” like the bumper sticker says. But I hate book reviewers.