How Loveta Got Her Baby (22 page)

“I just bought this,” he said, “by a miracle, ten minutes ago. These drills are clean as a whistle.”

“Wait a minute,” said the policeman.

“Officer, I'm a neurosurgeon,” the man said, “and this girl's going to die. Back off.”

He pulled on the trigger of the drill and it revved up and he carefully put his thumb on the side of Rhynie's head. He felt around and then full speed with the drill, drilled it through her dark hair, through her skull, just over top of her left ear. Skull-bits curled out over the tiny fake-pearl earring that she always wore there, and chewed bone and blood came out of that drill-hole in a long ooze. The neurosurgeon looked at her eyes again with the little light.

“Now take her to the hospital, I'll be there,” the man said.

Red lights flashed around them in the darkness.

“Take the boy too, he'll be all right.”

One operation later, Rhynie was okay. She recovered perfectly in every way except for the fact that she lost her memory for the night of the accident, and for everything that happened to her in the six months previously. That included her whole relationship with Justin Peach. He might as well never have existed. When she woke up from the coma, her family said, “You're off to Toronto, to recuperate.” Off she went. She never saw or gave a thought to Justin Peach again. For her, he never existed.

“And that was,” said Aaron Stoodley, “a recurrent theme in the life of Justin Peach, like a minor chord that lingered in the air.”

The policeman filled out a charge for careless driving that night, right on the spot, against Justin Peach, but then another officer, also on a motorcycle, pulled up and hit the same black ice and he spun out and fell too. He had a helmet on, and only broke his arm. So they tore the ticket up and you might say Justin got off easy that time.

“Got off easy?” said Aaron. “You'd only say that if you didn't know how Justin felt about Rhynie.”

Because Rhynie was by far the best thing that had ever happened to him. When she went to Toronto, he lay there for a week in bed on Patrick Street, in the basement. He couldn't smile anymore. He felt as though something had torn through him, like the avalanche that just missed him when he was a baby, like the rock and the snow that ripped through his family's house, through the house that was so skimpy, so threadbare, so poor that it never should have been built on the face of this earth at all.

breathing

Â

like

Â

that

I AM WRITING

late at night when it's easy: no one remembers it but us, even the gibbous moon which in that rare sky blew down the pathâand lit it up the way we feltâforgot it, as did the owl who turned away, small and dark over the wind-ripped black water of Soldier's Pond, so high above the city, so high we were, the line of surf laced all the way to Cappahayden, and the grass laid out horizontal by our breathing like that.

acknow-

Â

ledgements

Thanks, with love, to Cheryl, for bringing these stories together, to Nora and Jess for their acumen and support, to Willy and James.

Thanks, also with love, to Tom and Martha Keeping for taking care of me when I lived in Belleoram, to their children Tommy and Estella, to William May Sr., Sarah May, William Jr.

Thanks to James Langer, editor, and to everyone at Breakwater: Rebecca Rose, Elisabeth de Mariaffi, Rhonda Molloy.

Thanks to Martha Webb, of Anne McDermid Agency, in Toronto.

Thank you:

The Antigonish Review

,

The Fiddlehead

,

The Dalhousie

Review

,

subTerrain

,

Event

,

Prism International

, and the

Journey

Prize Anthology

, in which some of these stories first appeared.

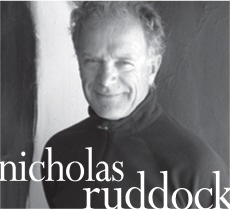

Nicholas Ruddock's award-winning poetry and fiction have been widely published in Canada and abroad. His story “How Eunice Got Her Baby” appeared in the Journey Anthology 19 and was produced by the Canadian Film Centre. His novel,

The Parabolist

(Doubleday, 2010), was shortlisted for the Toronto Book Award. Ruddock lives in Guelph, Ontario.