How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (2 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

Although we've known one another for a very long time, being together remains quite agreeable. Sometimes we don't even get around to watching a movie or reading books at all, because someone tells a favorite story and then everyone else begins reminiscing about wonderful times or places or people. Even though we've heard these same stories hundreds or even thousands of time before, they're still enjoyable. Felix, for instance, loves to tell about how he met George Washington and informed him that the German troops opposing him in the Revolutionary War would be spending Christmas night celebrating rather than guarding their camp. Based on this information, General Washington crossed the Delaware after dark on December 25, 1776, and took the Germans by surprise. Teddy Roosevelt is always ready to jump in and talk about his great adventures, including how he helped create eighteen national monuments. Leonardo might recall painting his masterpiece, the

Mona Lisa.

Every so often, I'm coaxed into recounting my first days of gift-giving, when I was a bishop in the early Christian church and even before that, as a small boy whose dream it was to bring comfort to those in need. Actually, I need very little coaxing.

Mona Lisa.

Every so often, I'm coaxed into recounting my first days of gift-giving, when I was a bishop in the early Christian church and even before that, as a small boy whose dream it was to bring comfort to those in need. Actually, I need very little coaxing.

Everyone always seems to have a story to share, and occasionally that includes Layla. But on most evenings, she prefers sitting quietly and listening to others. It isn't that she's too shy to speak. As Layla has demonstrated throughout the sixteen centuries we've been married, if she feels there is something that ought to be said, she will say it, and always in her pleasant, practical way. Layla is so intelligent, and so perceptiveâshe was the one back in the 1100s who helped us decide we must give toys to children instead of food, because the food would soon be gone but the toys would be lasting reminders that someone cared enough about them to bring gifts. It was also my wife who suggested that we deliver these gifts on three special nights rather than randomly throughout the year, so that we would have time to properly prepare, but more important, to help keep holiday traditions alive. And it was Layla, in the middle 1640s, who saved Christmas.

That's a story no one but Layla, Arthur, and I really knew until recently, when it came up by accident. We had not deliberately kept it a secret. For more than three and a half centuries, Layla simply didn't feel like talking about these particular Christmas-related events, which have been mostly overlooked by historians. Oh, they get some of the basic facts rightâfor a while in England, celebrating Christmas was against the law, until finally the people protested and got their beloved holiday back againâbut they have no idea of the important part Layla played in it.

None of our other North Pole companions did, either, until the night we sat down to watch a movie about one of history's more controversial figures. I should perhaps explain how we came to watch this particular film. It is our custom to take turns selecting what movie will be watched. If, for instance, Ben Franklin chooses on one night, it will not be his turn again until each of the other “old companions” has had the chance to make a selection. Everyone's choice is always honored, and it's interesting to see who likes to watch what. You would think, for instance, that Bill Pickett would want movies about cowboys, but he loves those colorful films about a boy wizard named Harry Potter. St. Francis likes the Disney cartoon

Peter Pan

; we've worn out several cassette copies, though the DVD version has lasted longer. Attila would watch

Some Like It Hot

every night, if he could. Christmasthemed movies like

It's a Wonderful Life

and

A Christmas Story

are always popular. None of us like films that contain a great deal of violence. We are people who love peace, not war. But movies based on history are always interesting. After all, some of us might have been there.

Peter Pan

; we've worn out several cassette copies, though the DVD version has lasted longer. Attila would watch

Some Like It Hot

every night, if he could. Christmasthemed movies like

It's a Wonderful Life

and

A Christmas Story

are always popular. None of us like films that contain a great deal of violence. We are people who love peace, not war. But movies based on history are always interesting. After all, some of us might have been there.

We all find it amusing that Arthur enjoys movies about himself. There are so many, most based on the colorful but inaccurate myth that Arthur was a British king who lived in a magical place called Camelot and fought evildoers with the help of a great wizard named Merlin. Arthur always claims to be embarrassed by such embellishment. In fact, he'd been a war chief in the 500s who, for a while, helped hold off Saxon invaders before they finally overran Britain. Layla, Felix, Attila, Dorothea, and I had found him lying wounded in a barn. We nursed him back to health, and he joined us in our gift-giving mission.

But books were written about mythical King Arthur, and poems and songs, too. When movies were invented (by Leonardo, Willie Skokan, and Ben Franklin, though they let others take the credit) there were soon films that also emphasized the Arthur legend rather than real history. We sometimes watch these at the North Pole, always at Arthur's suggestion. He tries to make it seem that he isn't secretly flattered; “Let's watch this new exaggeration,” Arthur might say. “How silly it is.” But his eyes stay glued to the huge widescreen television on which our movies are played.

One of the better versions, perhaps because of its wonderful songs, is a musical called

Camelot,

based on a fine book,

The Once and Future King,

by T. H. White. The theme of the movie, and the book, is that more is always accomplished by kindness than by violence. An actor named Richard Harris plays King Arthur in the movie. He does it quite well, though he doesn't look exactly like Arthur. He wears a beard in the movie, and Arthur never had a beard.

Camelot,

based on a fine book,

The Once and Future King,

by T. H. White. The theme of the movie, and the book, is that more is always accomplished by kindness than by violence. An actor named Richard Harris plays King Arthur in the movie. He does it quite well, though he doesn't look exactly like Arthur. He wears a beard in the movie, and Arthur never had a beard.

But a few weeks after we saw

Camelot

for perhaps the twentieth time, when Arthur's turn came around again he suggested we watch Richard Harris in another movie. We had just settled into our seats that evening, each of us enjoying a thick wedge of Candy Cane Pie, a special recipe by a wonderful Norwegian pastry chef named Lars. He makes the most fabulous desserts you can imagine, and many more you can't. We were thrilled when he agreed to join us at the North Pole. And, afterward, some of us began to put on a bit of additional weight, me perhaps most of all.

Camelot

for perhaps the twentieth time, when Arthur's turn came around again he suggested we watch Richard Harris in another movie. We had just settled into our seats that evening, each of us enjoying a thick wedge of Candy Cane Pie, a special recipe by a wonderful Norwegian pastry chef named Lars. He makes the most fabulous desserts you can imagine, and many more you can't. We were thrilled when he agreed to join us at the North Pole. And, afterward, some of us began to put on a bit of additional weight, me perhaps most of all.

“This movie has more real history than

Camelot,

” Arthur explained, setting down his plate of pie. “It's called

Cromwell,

and it's about the British Civil War in the 1640s.”

Camelot,

” Arthur explained, setting down his plate of pie. “It's called

Cromwell,

and it's about the British Civil War in the 1640s.”

“You were in England during that time, weren't you?” asked Sarah Kemble Knight. Sarah hadn't joined us until 1727, so she often requested such clarification.

“I was, along with Layla and Leonardo,” Arthur replied. “That was the same time that Santa and Felix were trying to introduce Christmas to the colonies in America.” Before he started the movie, he talked a little about Oliver Cromwell, a leader of the revolution against the British king. Leonardo added a few comments. Layla didn't. I thought she looked rather sad.

Then we lowered the lights and the film began. Richard Harris, playing Cromwell, stormed across the screen, pounding his fist and shouting. He did this in scene after scene, until after one particularly loud episode Layla spoke for the first time.

“He wasn't like that at all,” she said. Though her voice was low, everyone instantly paid attention, because it was unusual for Layla to comment during a movie.

“You knew Oliver Cromwell?” Teddy Roosevelt piped up. “I had no idea, Layla. Did you actually speak to him?”

Arthur paused the DVD and reached over to turn on the lights.

“Did Layla ever speak to Cromwell?” he replied. “Why, several times! If you knew the entire storyâ”

“There's no need to tell it,” Layla interrupted. “I'm sorry I said anything. Please, Arthur, start the movie again.”

But now everyone was curious. “It surely seems like there's something interesting here,” Bill Pickett remarked in his slow drawl. “I'd rather hear about it than watch the movie.” Several of our other companions loudly agreed.

Dorothea, who has been one of Layla's closest friends for over fifteen hundred years, quickly said, “If Layla doesn't want to talk about it, she shouldn't have to. Though, of course, I'd be very happy to listen if she does.”

Layla frowned. I could tell that there were things she was tempted to say, but for more than three hundred years she had never talked about her time with Cromwell, except to me in 1700 when we reunited back in America. Some memories can be painful as well as happy at the same time, and this, I knew, was one of those instances.

“You hardly ever tell stories, Layla,” Amelia Earhart pointed out. “It's usually Felix, or Teddy Roosevelt, or Santa. Please, take a turn now. You say that Cromwell wasn't loud, that he didn't shout like the actor in the movie?”

“No, I never heard him shout,” Layla said, choosing her words carefully. “He was a determined man, someone who I completely disagreed with about Christmas. Oliver Cromwell thought Christmas was sinful, and tried to end it forever. But he wasn't

evil,

you see. That was what made it harder whenâ”

evil,

you see. That was what made it harder whenâ”

“When what?” Amelia urged.

Layla looked at me, a question in her eyes. I knew she was silently asking whether I thought she should continue. It wasn't a matter of me granting permission. Layla never asks, or needs, my permission to do anything. But she values my opinion, as I always do hers.

“I think this might be a story that should finally be told, Layla,” I said, looking around the room. Most of our good, dear friends were perched on the edges of their seats, watching Layla and obviously hoping she would tell whatever the story was about Oliver Cromwell and his attempt to end Christmas. “I've often said that it's wrong for me always to get credit for almost every good thing in Christmas history. Perhaps everyone here should know about your incredible accomplishment, too.”

“I really did very little,” Layla replied. “It was the othersâElizabeth and Alan Hayes, for instance, and all those brave apprentices in London, and Avery Sabine, though he surely didn't mean to help us. And . . . andâ”

“And Sara,” Arthur added, his voice very soft.

“And Sara most of all,” Layla agreed. She sat quietly for a moment, thinking hard. “All right. I'll tell the story, if everyone wants to hear it.”

“Please do,” begged Teddy Roosevelt, who usually preferred telling stories to listening. “Who were Elizabeth and Alan Hayes, Layla, and what about apprentices and this Avery fellow? Who was Sara, who seems so special to you? And why haven't you mentioned any of this before?”

“Some things are almost too important, and perhaps too painful, to mention,” Layla said quietly before drawing a deep breath. “All right, then. In 1645 and again in 1647, the British Parliament voted that celebrating Christmas was against the law. I had spent quite a bit of time with Arthur and Leonardo at our secret toy factory in London, andâ”

“Please, Layla, share more than that,” Amelia pleaded. “Why were you in England in the 1640s, when Santa was in America?”

“Well, remember, he wasn't called Santa then,” Layla reminded. “That name only came fifty or sixty years later. Before that we all called him by his given name, Nicholas. He was in America because we wanted to encourage Christmas celebrations there. I stayed behind since there were still things to do in Europe and England, especially in England. Now, Oliver Cromwell wasn't the only Englishman to oppose Christmas. The story goes back a very long way. There are lots of details. One is even related, in a manner of speaking, to the Candy Cane Pie that Lars baked for us tonight. Are you sure you want to hear it all?”

This time, I answered. “Yes, Layla, tell everything. And start, please, at the very beginning, because I doubt some people here even know very much about your childhood. Don't imagine that we'll be bored. It will be our pleasure to listen.”

And so, Layla told her story. It was such a magical evening that the next day I called a writer from Texas who helped me with my autobiography. I asked him to capture Layla's words on paper so that you, too, could enjoy the story of how Mrs. Claus saved Christmas.

Â

âSanta Claus

The North Pole

The North Pole

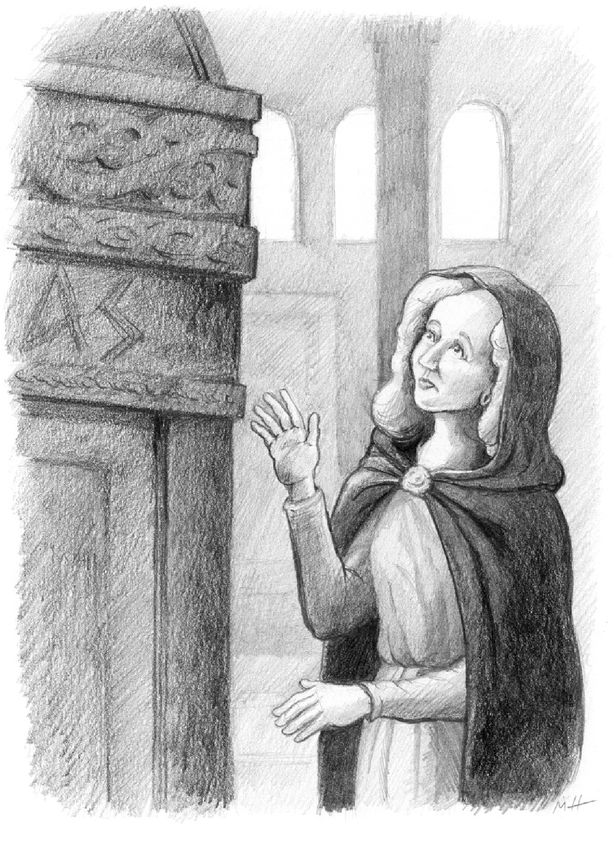

As I stood as close to the tomb as I could, a strange feeling came over me. It wasn't sadness, though I felt very bad for the crippled and poor people and wanted with all my heart to do something to help them.

CHAPTER

One

One

Â

Â

Â

Â

I

f I start at the very beginning,we must go back to the year 377 A.D., when I was born in the small farming town of Niobrara in the country then known as Lycia. Its modern-day name is Turkey. With a population of two hundred, Niobrara was, in those days, a medium-sized community. Almost everyone living in my hometown at that time had something to do with growing, grinding, or selling grain, though a few families had groves of dates instead. I know many people today believe most of Turkey is just sand and wind, but there are some very green, fertile places, and Niobrara was in one of them. Most visitors to Niobrara were travelers briefly passing through on their way to bigger, more important cities and ports. And, always, bands of poor nomads would briefly camp on the outskirts of town, hoping to earn a few days' wages by helping harvest crops.

f I start at the very beginning,we must go back to the year 377 A.D., when I was born in the small farming town of Niobrara in the country then known as Lycia. Its modern-day name is Turkey. With a population of two hundred, Niobrara was, in those days, a medium-sized community. Almost everyone living in my hometown at that time had something to do with growing, grinding, or selling grain, though a few families had groves of dates instead. I know many people today believe most of Turkey is just sand and wind, but there are some very green, fertile places, and Niobrara was in one of them. Most visitors to Niobrara were travelers briefly passing through on their way to bigger, more important cities and ports. And, always, bands of poor nomads would briefly camp on the outskirts of town, hoping to earn a few days' wages by helping harvest crops.

Other books

The Season of Migration by Nellie Hermann

Whatever You Love by Louise Doughty

Assignment - Sulu Sea by Edward S. Aarons

Touch the Stars by Pamela Browning

A Life To Waste by Andrew Lennon

To Master and Defend (The Dungeon Fantasy Club Book 2) by Anya Summers

The Safety of Nowhere by Iris Astres

The Arrangement 9 by H.M. Ward

Fallen Idols by J. F. Freedman

White Lilies by Bridgestock, RC