How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (30 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

“If we do something similar here, it will only be effective if we act as one,” I pointed out. “Everyone must be agreed beforehand that we will stand together and not waver in any way. Mayor Sabine will certainly order us to go home, and he will threaten us with prison or even the possibility of direct musket-fire from the Trained Band. But if there are enough of us, nonviolent but defiant, all he can use against us are words. The mayor is not a stupid man. If a peaceful Christmas demonstration is marred by bloodshed caused by the Puritans, the whole country might well rise up against them, and Sabine can't risk that.”

“You say we need a thousand people involved, maybe more,” a gap-toothed farmer said. “How are we supposed to find them?”

“In the same quiet way the first few invited here tonight took it upon themselves to invite others,” I replied. “All of you have friends you trust, and those friends will have friends, and so on. An abiding love of Christmas, and a determination not to lose that wonderful holiday, are the only qualifications necessary. Of course, the more people who know, the greater the danger that someone will be a spy for the mayor. Well, that's a risk we must take.” As I spoke, I worried I wasn't effectively communicating the urgency of our task, and what I was asked next proved me right.

“Do we really need to do this?” an elderly woman wanted to know. “I miss singing carols in the streets, but last Christmas my family still enjoyed roast goose. We gave each other little gifts, and no one came to arrest us.”

“The laws are stricter this year,” Alan pointed out. “Blue Richard and his gang are promising that, on December 25, they'll break into homes where Christmas is being celebrated and drag everyone there off to jail. They might miss your home this time, but sooner or later it will be your turn. We're not trying to save Christmas just in 1647. We're trying to preserve it for the future. If we don't act now, people will gradually decide that the Puritans really can take Christmas away, and if enough of them eventually accept this awful new law, then Christmas

will

be gone forever.”

will

be gone forever.”

“And there's even more danger to Christmas than that,” said another man, and my eyes widened and my heart leaped, because his face and voice were so familiar. Arthur, my friend of more than one thousand years, had come back to England!

“Christmas has been gone from Scotland for sixty-four years, taken from the people by Scottish Parliament then and never restored since,” Arthur said, grinning as he looked toward me and saw I'd recognized him. “At first, the people there thought it would only be a matter of a year or two before their Puritan leaders came to their senses and let everyone choose whether or not to celebrate the holiday, but it never happened. Across the ocean in their American colonies, the Puritans have banned Christmas for more than twenty-five years. Now, if they succeed in banning Christmas in England, why, they may try the same thing in other countries until, finally, a December 25 will come where no one in the world will dare sing a carol or give a small gift in honor of the birth of Jesus. But we're gathered here tonight. Let this be the moment when we decide this cannot, will not, happen. Let this be the moment when we agree that, no matter what the risk, we join together and take the first step to save Christmas forever.”

I understood something then, listening to Arthur. Because we know them so well, we often take our family or friends for granted. We don't appreciate them as much as they deserve. Now, after spending over a thousand years in Arthur's company, I finally realized the extent of his ability to persuade people to act. Perhaps he had only been a war chief and never a magical king, but he was a great leader. He could put words together in a speech to inspire followers in a way I never could. When I talked about the Apprentice Protest, I made the people in the barn think about the possibility of a single demonstration in local streets. Arthur talked about saving Christmas for the whole world, and suddenly everyone understood all that was really at stake. It wasn't just the holiday. It was the right of people to believe as they chose, rather than being told what they could and could not believe. By protecting Christmas, we would even be protecting the rights of those who

didn't

want to celebrate it.

didn't

want to celebrate it.

Everyone cheered, and some began chanting, “This is the moment!” until Arthur finally raised his hands and asked them to stop “because we don't need the sound of our voices reaching the mayor's ears just yet!” But now there was a sense of excitement, of exhilaration, that hadn't been there before. Arthur suggested that everyone think about how to recruit more supporters and that we meet back at the barn in two weeks. There was a roar of approval, and people slapped one another on the back and chattered happily as they began making their way home through the chilly, dark night.

Arthur came over and hugged me. I introduced him to Alan as “a dear old friend of mine and my husband's. I thought, though, he was living in Germany.”

The two men shook hands, and Arthur said, “I'd heard such fine things about the countryside around Canterbury that I just had to come see for myself. I'm staying with a farm family, helping out with the chores, and when one of them told me about this meeting tonight I just thought I'd come with him, since I love Christmas so much. Layla, perhaps we can meet tomorrow evening and catch up with each other. I just had a letter from your husband Nicholas in America, and I'm sure you'll want to read it.”

Alan invited Arthur to join us tomorrow for dinner and gave him directions to the cottage. I hugged Arthur a second time, and then walked home with Alan feeling completely elated.

This is going to happen,

I thought to myself.

Christmas is really going to be saved.

This is going to happen,

I thought to myself.

Christmas is really going to be saved.

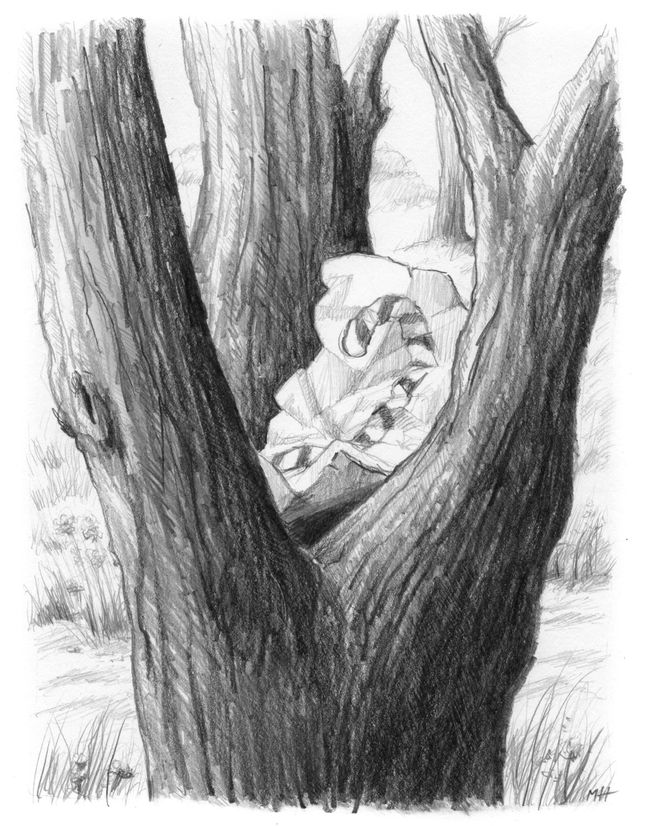

Arthur distributed candy canes and explained how they were to be used. When one of us needed to meet with everyone else, he or she would leave a small drawing of a candy cane stuffed in a crevice of the big tree outside the Hayes cottage.

CHAPTER

Eighteen

Eighteen

Â

Â

Â

Â

S

ara didn't like strangers coming into her home. When Arthur arrived for dinner, she nodded stiffly in his direction, then resisted all his efforts to coax her into conversation. But Alan and Elizabeth warmed to my old friend quickly, so despite Sara's shynessâwhich, I informed her afterward, bordered on rudenessâwe shared a happy meal and pleasant talk. Arthur told about himselfâthat he was a native of England who'd been living in London, then moved abroad for a bit “because of political and religious discomfort” before returning to his homeland, since he missed it so much. By apparently telling everything, he was able to conceal his deepest secrets, specifically how he was about eleven hundred years old and an important member of Father Christmas's gift-giving companions. Once again, I marveled at his amazing ability to draw people to him. After an hour of his company, I could tell Elizabeth and Alan would have followed Arthur anywhere. Only Sara didn't seem captivated by him. As soon as dinner was over, she excused herself and climbed up to the loft.

ara didn't like strangers coming into her home. When Arthur arrived for dinner, she nodded stiffly in his direction, then resisted all his efforts to coax her into conversation. But Alan and Elizabeth warmed to my old friend quickly, so despite Sara's shynessâwhich, I informed her afterward, bordered on rudenessâwe shared a happy meal and pleasant talk. Arthur told about himselfâthat he was a native of England who'd been living in London, then moved abroad for a bit “because of political and religious discomfort” before returning to his homeland, since he missed it so much. By apparently telling everything, he was able to conceal his deepest secrets, specifically how he was about eleven hundred years old and an important member of Father Christmas's gift-giving companions. Once again, I marveled at his amazing ability to draw people to him. After an hour of his company, I could tell Elizabeth and Alan would have followed Arthur anywhere. Only Sara didn't seem captivated by him. As soon as dinner was over, she excused herself and climbed up to the loft.

“I don't think your young friend likes me,” Arthur commented when the dishes were cleared away and he and I had gone outside to walk a bit and talk. “Did I say or do something to offend her?”

“That's just Sara's way,” I replied. “She is bashful around those she doesn't know very well, but she must learn to be friendly and gracious even when she feels uncomfortable. I'll speak to her about it. Now, last night you mentioned a letter from my husband. Did you bring it with you?”

“Of course,” Arthur said, reaching into a pocket and handing me several pages of creased, well-worn paper. “After Leonardo and I arrived in Nuremberg I wrote to Nicholas right away, telling him we'd closed the London toy factory, at least for a while. I

didn't

tell him you'd remained behind in Canterbury. Perhaps you wrote him about that yourself? You didn't, did you? Well, that, of course, is your decision. Anyway, it must have taken him a long time to receive my letter, and it certainly took months for his reply to reach me. Here it is; I'll just wander around a bit while you read.”

didn't

tell him you'd remained behind in Canterbury. Perhaps you wrote him about that yourself? You didn't, did you? Well, that, of course, is your decision. Anyway, it must have taken him a long time to receive my letter, and it certainly took months for his reply to reach me. Here it is; I'll just wander around a bit while you read.”

Arthur disappeared over a small knoll, and I settled down in the fading fall grass with Nicholas's letter. Even his handwriting, so grand and flowing, made me miss him. It had been so many years since we had been together! Well, we wouldn't be apart much longer.

The first part of the letter described his life with Felix in the New World. They were now living in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, and very much enjoying the holiday customs there. Dutch children expected visits from St. Nicholas on December 6, and there were enough of them to keep Nicholas and Felix quite busy making and delivering toys on time. But the British colonies were still Puritan-dominated, and Father Christmas was not welcome in themâan extension, Nicholas noted, of the Christmas troubles in England.

“Though I'm sorry you felt the London toy factory must be closed, I certainly understand and agree with that decision,”

he wrote.

“What a terrible thing it is when a few close-minded people force their own prejudices on everyone else. But I hope that, like me, all of you continue to believe in the overall goodness of human nature. Bad times do not last forever. Because the vast majority of the English people want Christmas, I know that they will, somehow, get it back again.”

he wrote.

“What a terrible thing it is when a few close-minded people force their own prejudices on everyone else. But I hope that, like me, all of you continue to believe in the overall goodness of human nature. Bad times do not last forever. Because the vast majority of the English people want Christmas, I know that they will, somehow, get it back again.”

Then, to my amazement, my husband addressed me directly. He had not done this in his previous letters. After more than twelve centuries of marriage, we did not need to constantly reassure each other of our love. But, separated from his wife by a vast ocean, Nicholas still instinctively understood that just now I did need some extra words from him.

“Layla, none of Arthur's recent letters have made much specific mention of you,”

Nicholas wrote.

“I don't know for certain, but I suspect that you are planning, in some way, to challenge the English Parliament's outlawing of Christmas. I won't insult you by pointing out the dangers of such action. You will have considered them for yourself. I will only remind you that whatever you do, you have my complete support. We are now, as we have always been, equal partners. Though I can't share these difficult times with you in person, I am always with you in your heart. Do whatever you believe is right, and then board a ship and come across the ocean to me, so I can put my arms around you again after so many years.”

Nicholas wrote.

“I don't know for certain, but I suspect that you are planning, in some way, to challenge the English Parliament's outlawing of Christmas. I won't insult you by pointing out the dangers of such action. You will have considered them for yourself. I will only remind you that whatever you do, you have my complete support. We are now, as we have always been, equal partners. Though I can't share these difficult times with you in person, I am always with you in your heart. Do whatever you believe is right, and then board a ship and come across the ocean to me, so I can put my arms around you again after so many years.”

I suppose I sat there for a half hour or more, tears dripping down my cheeks onto the grass, before Arthur returned. He sat down beside me and patted my shoulder.

“I miss my husband so much,” I murmured. My throat felt thick, and my eyes burned from the salty tears.

“Of course you do,” Arthur said. “You know, Layla, we have received these wonderful giftsâapparently endless life, the ability to travel at amazing speeds, the opportunity to spread joy and comfort to children through our holiday mission. But they come with a price, as all worthwhile things do. You can no more let the Puritans' banning of Christmas go unchallenged than you can resist breathing. That's why I came back to England. I knew you would be planning something, and now the moment draws close. I'll help in any way I can and, afterward, I'll take you to the dock and smile as you board a boat that will take you across the ocean to your husband.”

“Thank you,” I gulped. Then I resolutely wiped my eyes, cleared my throat, put Nicholas's letter in the pocket of my cloak, and got to my feet. “All right, Arthur,” I said. “I've had my weepy moment, and that is the end of that. Now, we have a Christmas Day protest to plan.”

And we did. Back in the Hayes cottage, gathered with Alan and Elizabeth around the table while Sara sulked up in her loft, Arthur and I discussed what might happen, and where. His experience as a war chief came in handy, because he could guess how the Canterbury authorities and Trained Band would react.

“If we have two thousand protestors, and I believe we will, we can't have them all trying to enter the city through the same gate,” Arthur warned. “The guards will see them comingâthe town is in a valley, after allâand simply shut the gate tight. The protest won't be as effective if Mayor Sabine and his holiday-hating cronies stroll the streets while the demonstrators are held outside the city walls. There are six gates in all. We'll need to have the protestors divided into six groups, each entering the city at the same time through a different gate. That way, even if one or two of the gates are closed to prevent some of us from entering, the others will still get inside the walls.”

“What about once we all are inside?” Elizabeth wanted to know. “If we're in six different parts of the city, won't that lessen the impact of having thousands of people involved?”

Other books

Caress of Flame by King, Sherri L.

Fairer than Morning by Rosslyn Elliott

Til Death (Immortal Memories) by R. M. Webb

The Orchardist by Amanda Coplin

6.The Alcatraz Rose by Anthony Eglin

The Jewel Collar by Christine Karol Roberts

Tempted by Rebecca Zanetti

Beautiful Sacrifice by Elizabeth Lowell

Falling Softly: Compass Girls, Book 4 by Mari Carr & Jayne Rylon

Slightly Sinful by Mary Balogh