How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (39 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

After scrubbing ourselves thoroughly with well water and changing into wonderfully clean clothes, we ransacked cupboards and finally assembled a Christmas dinner of dried fruit, potatoes, a few stringy winter vegetables, and fresh water. There was also bread, but Arthur, Alan, Elizabeth, and I had already consumed quite enough bread during our week in prison. We wouldn't want any more for quite a while. Afterward, I produced some candy canes for dessert, and we sang a few more carols. Almost as soon as it was dark, we all felt quite exhausted and were ready for bed. Arthur, who was staying with us for the night, paused as he prepared to go outside for a final washing-up at the well.

“Now,

that

was quite a Christmas!” he declared. By the time he came back inside, everyone else was already asleep.

that

was quite a Christmas!” he declared. By the time he came back inside, everyone else was already asleep.

I settled, over the next forty years, for watching her whenever I could. I personally delivered Christmas presents to her son, Michael, and to her daughters. The three youngest were Elizabeth, Gabriella, and Rose. The oldest girl, the first child born to Sara, was named Layla.

CHAPTER

Twenty-four

Twenty-four

Â

Â

Â

Â

H

istory includes many great events, but very few neat, tidy endings. What happened in Canterbury on December 25, 1647, did save Christmas. It also contributed to the eventual fall of the Puritan government and the restoration of the monarchy in England. But all this took quite a long time. We didn't wake up on December 26 to find everything back the way it was before the king lost his throne and Christmas was abolished.

istory includes many great events, but very few neat, tidy endings. What happened in Canterbury on December 25, 1647, did save Christmas. It also contributed to the eventual fall of the Puritan government and the restoration of the monarchy in England. But all this took quite a long time. We didn't wake up on December 26 to find everything back the way it was before the king lost his throne and Christmas was abolished.

What we did find was that, sometime during the night, Margaret and Sophia Sabine were whisked off by carriage. Word reached Canterbury later that the mayor's wife and daughter had moved permanently into the family's house in London. Margaret Sabine informed all her new neighbors that Canterbury was no longer a fit place for godly people to live. Sophia Sabine, I suppose, soon did meet a suitable husband, and I hope she enjoyed a long, happy marriage. What a brave girl she was, rushing out to save her father from the clubbing he was about to receive! But I really don't know what happened to Sophia. I do know that she and Sara never saw each other again.

Mayor Sabine stayed behind in Canterbury. It quickly became clear that most of the people there now thought of him as a laughingstock. Whenever he would bellow out commands, nobody listened. His reputation among the Puritan leaders in London suffered, tooâall of England heard about the Canterbury Christmas March, and how the city's mayor had acted like such a coward. Avery Sabine never did get the high position in government he had both coveted and expected. Instead, he had to keep operating his Canterbury businesses. Customers came into his mills and shops because it was convenient, not because they respected the owner.

In the spring of 1648, Sabine made one last attempt to regain his local influence. He formally charged Arthur, Alan, Elizabeth, and me with assault. Sabine also brought assault charges against a dozen or so other protestors who he had noticed during the demonstration, John Mason among them, and the man who had nailed the “Christmas and King” proclamation to the mayor's front door was accused by Sabine of treason. But this time, there was no Blue Richard Culmer swooping into Canterbury to arrest us. After our impressive Christmas march, Culmer never came to Canterbury again. He was a cruel man, but also a clever one. He realized his nasty tactics would not be effective anymore in a community where ten thousand people were ready to stand up against him. Instead, Colonel Hewson politely notified us all that we would be tried by a jury of our peers, as traditional English law required. He and his men escorted usâ

not

in chainsâto Leeds Castle, where we were kept in comfortable quarters rather than cells while the trial took place. Elizabeth arranged for Sara to stay with John Mason's wife. Mayor Sabine testified at the trial that he had been pulled down by Arthur, Elizabeth, Alan, and me and thoroughly beaten by our “hooligans” before he had been able to fight his way to freedom. His ability to make up stories was amazing, but in May the jury unanimously found us all not guilty, and we were free to get on with our lives.

not

in chainsâto Leeds Castle, where we were kept in comfortable quarters rather than cells while the trial took place. Elizabeth arranged for Sara to stay with John Mason's wife. Mayor Sabine testified at the trial that he had been pulled down by Arthur, Elizabeth, Alan, and me and thoroughly beaten by our “hooligans” before he had been able to fight his way to freedom. His ability to make up stories was amazing, but in May the jury unanimously found us all not guilty, and we were free to get on with our lives.

And those lives were different. Elizabeth could no longer work for the Sabines. She had to take a job as a milkmaid on a local farm. She was paid much less, and the work was harder. But she gladly accepted this, saying it had been well worth the sacrifice to speak out on behalf of Christmas. Because his role in the protest had become well known and because Puritans still controlled most of England's shipping business, Alan could not find a place on any crews. So he had to start doing farmwork, too. At least he was no longer away from his wife and daughter on long voyages.

Sara, of course, had no more daily lessons with Sophia. But she did, finally, have lots of friends her own age and that helped ease her sense of losing someone who had been as close to her as a sister.

Just as soon as the jury set me free, I left Canterbury. I had to. I had been there almost six years and hadn't aged a bit. It was very hard to go. I told my friends there that I was going to briefly visit people I knew in Nuremberg, and then finally cross the Atlantic Ocean to reunite with my husband. Alan and Elizabeth told me I was always welcome in their home and that they would miss me very much. Sara cried, and begged me to never forget her. That was an easy promise to make. I had plans for my precious girl. As part of them, I did sail for Germany in the summer of 1648, but I had no intention of making the longer journey to America for some time yet.

Arthur guessed the reason. “You mean to ask Sara if she will become one of our gift-giving companions,” he said one night in Nuremberg, where he and Leonardo were helping at the toy factory until they felt the time was right to reopen their factory in London. “That's why you've written to Nicholas that you can't come to the New World immediately.”

“She is perfectly qualified to join our company,” I replied. “You saw for yourself during the protest that she is brave and intelligent and completely dedicated to Christmas. I would reveal our mission to her now if she weren't still a child. I know if I did, she would come with me immediately, but it would break her parents' hearts to lose her. So I'm waiting until she is completely grownâtwenty or twenty-five, let's say. Then she can come with me to America, and we'll join Nicholas and Felix in spreading Christmas joy there.”

“What if she doesn't want to go?” Arthur asked. “I know she's told you she dreams of traveling to great cities, but young people do change their minds.”

“Sara won't,” I said confidently, and I waited. While I did, the events in Canterbury on Christmas Day 1647 had further effects on the future of England.

All over the country, people who were unhappy with heavy-handed Puritan rule took note of the march and how it intimidated their new, rigid rulers. They were also pleased when the grand jury refused to convict the march's leaders of any crimes. Support for King Charles spread to the point that, by the summer of 1648, there was civil war again. It was eventually put down by Oliver Cromwell, who led his army all the way into Scotland and Ireland, ruthlessly beating back opponents until, finally, England was really run by the military rather than Parliamentâand Cromwell led the military. I hated the fighting, of course, and was especially grieved when King Charles I was executed in January 1649. It was Oliver Cromwell's idea, and I was so sorry that this essentially decent man had decided it was all right to use such awful tactics to achieve his purposes.

For Oliver Cromwell, afterward, things only got worse. Like King Charles before him, he became frustrated when Parliament wouldn't do exactly as he wanted. When its members voted to keep themselves in office rather than schedule elections, Cromwell dissolved Parliament and ended up creating a new one composed entirely of his own trusted supporters. These included the street preacher Praise-God Barebone, and the group became known as “Barebone's Parliament.” They really had no power. Cromwell was named Lord Protector of England. He could have called himself the king, but that office had been legally abolished in 1649.

Oliver Cromwell tried hard to rule fairly, based on his religious and political beliefs. Non-Puritans like Catholics and Jews were allowed to quietly worship as they pleased, though they were given no power in Cromwell's government. Cromwell tried to establish schools for working-class children and to make laws based on the best interests of everyone instead of just the rich. He never wavered in his hatred of Christmas, and, while he reigned, celebrating it was still against the law. But, after what we did in Canterbury, there were no more threats of punishment for those who wanted to sing carols or feast on goose or exchange gifts in the privacy of their homes. Parliament couldn't risk more rebellion. The Puritans could, and did, pretend they had ended Christmas forever because there was no longer singing in the streets, and because many shops remained open on Christmas Day. But everyone knew better. Still, without public festivities there was a difference. We had managed to

save

Christmas, but it would be quite a long time before it was entirely restored as a wonderful holiday.

save

Christmas, but it would be quite a long time before it was entirely restored as a wonderful holiday.

The anti-Christmas laws remained in partial effect until 1660. When Oliver Cromwell died in 1658, Puritan rule was highly unpopular with most of the English people. Cromwell was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son Richard, but Richard had little of his father's charisma and determination. Two years later, he stepped down and Parliament invited Prince Charles, the oldest son of the former king and queen, to come back to England and rule. King Charles II immediately announced “the Restoration,” which effectively abolished all the laws passed by the Puritans.

So, celebrating Christmas, in private

and

in public, was once again perfectly legal. But, for more than another one hundred and fifty years the magic and wonder of the holiday didn't entirely return to England.

and

in public, was once again perfectly legal. But, for more than another one hundred and fifty years the magic and wonder of the holiday didn't entirely return to England.

Many business owners

liked

the idea of their employees having to come to work on December 25, instead of enjoying a paid holiday. Working-class people still felt intimidated by the long years of holiday oppression. Arthur returned to London and reopened the toy factory there, since enough families once again allowed their children to receive gifts from Father Christmas. But no more happy crowds marched through cities singing and playing games and calling on their richest neighbors to share holiday snacks. Most people only dared to celebrate the holiday in their homes. And not all of Britain enjoyed even that limited pleasure. Christmas was not officially restored as a full holiday in Scotland until 1958. So, while Christmas flourished across the English Channel in Europe, it remained almost a half-hearted holiday for many in England until two important events.

liked

the idea of their employees having to come to work on December 25, instead of enjoying a paid holiday. Working-class people still felt intimidated by the long years of holiday oppression. Arthur returned to London and reopened the toy factory there, since enough families once again allowed their children to receive gifts from Father Christmas. But no more happy crowds marched through cities singing and playing games and calling on their richest neighbors to share holiday snacks. Most people only dared to celebrate the holiday in their homes. And not all of Britain enjoyed even that limited pleasure. Christmas was not officially restored as a full holiday in Scotland until 1958. So, while Christmas flourished across the English Channel in Europe, it remained almost a half-hearted holiday for many in England until two important events.

First, in 1840, England's young queen Victoria married a German prince named Albert. Albert loved all Germany's wonderful Christmas traditions, including caroling in the streets, church services thanking God for sending his son, and even Christmas trees. With their queen encouraging Christmas celebrations, people in England began to openly enjoy the holiday. Then, in 1843, a fine British author named Charles Dickens published a short novel called

A Christmas Carol.

(I'm glad to say my husband and the rest of our company played a part in this; that story is included in Nicholas's book.) Mr. Dickens's amazing tale of an old miser named Scrooge and a crippled boy named Tiny Tim was a sensation all over the country. Between Prince Albert and

A Christmas Carol,

by 1844 Christmas in England was once again a time of great happiness, even for the poorest people.

A Christmas Carol.

(I'm glad to say my husband and the rest of our company played a part in this; that story is included in Nicholas's book.) Mr. Dickens's amazing tale of an old miser named Scrooge and a crippled boy named Tiny Tim was a sensation all over the country. Between Prince Albert and

A Christmas Carol,

by 1844 Christmas in England was once again a time of great happiness, even for the poorest people.

By then, of course, I had been reunited with my husband for almost one and a half centuries. But Sara was not with us.

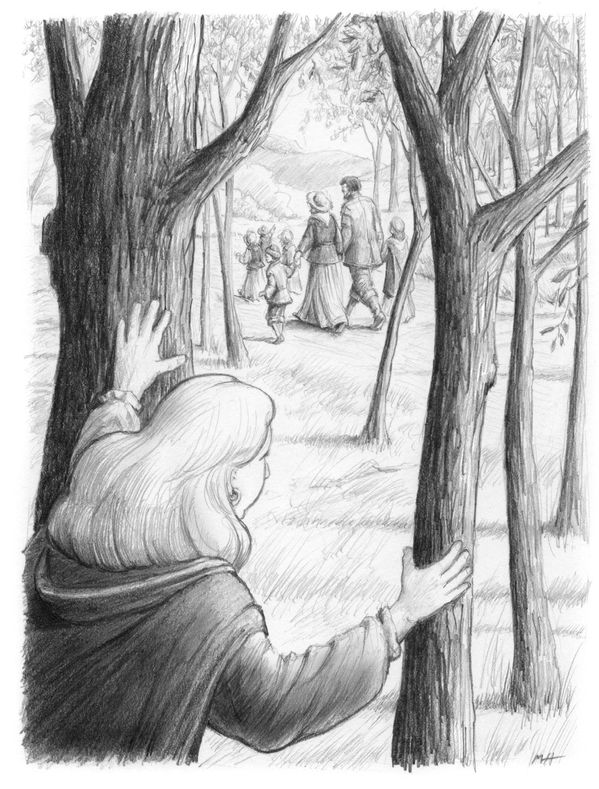

After I left Canterbury, I stayed with Attila and the others in Nuremberg. Several times each year, I would go back to England, and, from a distance, feel my heart swell with pride as I watched my beloved girl continue to grow up. Sara was so intelligent, so

good

!

good

!

Though, for the time being, I could not let her see me, I still could enjoy being near her. When she was sixteen, she started a free school for farm girls, teaching them to read and write and do sums. Only three or four came at first, for it was unusual for girls to learn these things. But they told their friends, and more girls came, until finally Sara was giving lessons to a hundred. This was, I knew, more proof that Sara not only deserved but needed to join our gift-giving mission. If she took so much pleasure in helping a hundred children, how much more delightful she would find bringing gifts and hope to hundreds of thousands! I decided I would reveal myself and our secrets to her when she was twenty. I was anxious to be with her again, and also anxious to join Nicholas in America. When I arrived with Sara, it would be like presenting my wonderful husband with a grown daughter! He would love her as much as I did, I knew.

Other books

Italian Billionaire's Black Love (BWWM Interracial Romance) by Mya Black, Nicki J.

Bobcat: Tales of the Were (Redstone Clan) by Bianca D'Arc

The Mob and the City by C. Alexander Hortis

Taming Graeme (Taming the Billionaire) by Britton, Kate

Green Tea and Black Death (The Godhunter, Book 5) by Sumida, Amy

Master of the Inn by Ella Jade

Heart of Perdition by Selah March

Now You See It by Richard Matheson

Legacy (Alliance Book 3) by Inna Hardison

Guardian of the Gate by Michelle Zink