How Music Works (26 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

though a

true

nighttime ambience would likely include distant traffic, wind, a faraway plane, a couple of barking dogs, and, yes, a whole bunch of crickets. All of this would be, if heard all together, perceived as sonic chaos, and wouldn’t convey the tranquil nighttime mood that was intended. Our brains

organize the sound we hear in the same way our eyes selectively see. Recre-

ating what something sounds like, what a sound or sonic environment

feels

like, in a music recording or a film, has become an art that some people are better at than others.

Some musicians and producers ignored this isolate/deconstruct/recon-

struct dogma. The Cowboy Junkies made their first record using one mic to

record the whole band, and Steve Earle did something similar with a bluegrass 144 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

band. In 2012, I participated in some recordings on which some brass players were seated next to one another (which meant their playing wasn’t isolated)

while others were in completely isolated booths. Furthermore, the guitar and vocal tracks had been recorded beforehand in an apartment with no sound

isolation at all. Nowadays the dogma isn’t adhered to quite as strictly; it’s one of a number of approaches one can take, and sometimes many approaches

coexist on the same recording.

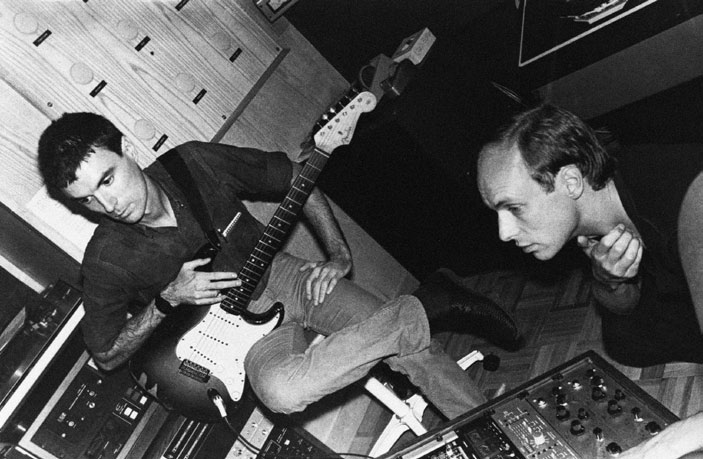

By the time Talking Heads recorded our second record,

More Songs About

Buildings and Food

, we had become friends with Brian Eno. We liked his music, so we asked ourselves, “Why not have him be our producer? At least he gets

what we’re about, and we’re already friends.” Friendship, common interests,

and sensibilities seemed more important to us, especially based on our previous experience, than whatever technical skills or hit-making track record he might have possessed.

Seeing that we had turned into a pretty tight live band, Eno suggested we

play live in the studio, without all of the typical sonic isolation. His semi-blasphemous idea seemed worth a try, despite the risk of it resulting in a

muddy recording. Removing all that isolating stuff, or at least most of it, was like being able to breathe again. The result sounded—surprise!—more like

us, like the way we were used to hearing ourselves on stage, and so our playing was more inspired (or so we felt). Removing some of the sound-absorbent

stuff meant that you could hear the faint sound of guitars in the background of the drum tracks, and maybe an electric piano might be audible in the background of the bass track. There wasn’t absolute separation of instruments,

but we felt that the comfort factor more than compensated for this technical challenge. Eno even believed that the two mics he placed in the center of the room might be all that was needed to capture the entire band. That proved not to be entirely the case, though the sound of those mics did come in handy as a kind of supplementary ambience.

Eno suggested we try some fairly unconventional vocal recording approaches

also. Sometimes I sang along to all the music after it had been recorded, mic in my hand, often right in the control room with the speakers blasting, like a big live sound system positioned on either side of me. This wasn’t a kosher

recording technique back then. The sound of the band coming through the

speakers behind me could be heard on my vocal tracks, and typically producers would insist that singers go into silent padded booths. That isolation works DAV I D BY R N E | 145

for some, but it requires a leap of faith, as even the greatest headphone mix doesn’t sound as good as singing in front of a live band or blasting speakers.

You have to imagine while you’re singing in the booth that the not-so-exciting band you’re hearing over the headphones is one day going to sound better

than it does. I wondered how those professional singers did it. I wasn’t going to acquire those skills instantly, so, to his credit, Eno’s suggestion was a good workaround. I’ve heard this is what Bono does, too.

Most of the songs we recorded we had been performing live for a while,

though a couple—“Found a Job” and “The Big Country”—were brand new,

written for that record. In subtle ways those songs were shaped in the stu-

dio, though I’d initially written them as something I could play solo on my

guitar. This process of learning new songs just before recording them would

become commonplace for us. It was practical, but it meant that the songs

often didn’t get as “broken in” before recording as they would have after a

series of live performances.

More Songs About Buildings and Food

took three weeks to make. I think

77

might have taken two weeks, including mixing. That meant that the recording costs advanced (i.e., loaned) to us by the record company were low enough that, even with modest sales, we were able to pay them back relatively quickly. It also meant that the record company itself would probably

make a profit on the record, ensuring (we hoped) a continuing relationship

between them and the band.

Did we think about those costs, and did they affect the way we recorded

the music? Do music-business finances, especially those dictated by record-

ing technology, in some ways determine what music sounds like? Absolutely.

Limited finances acted as a set of creative restrictions, which, for us, was generally a good thing. Decisions about whether an overdubbed part worked or

was well played had to be made relatively quickly. Indecision cost time, which we knew was constrained by our budget. The question of whether to rear-range a song or try it in a manner different from how we played it live often never came up—these were non-decisions that saved time and money. Using

few outside players, who would have had to be paid, was another cost-saving

move. These factors make certain records sound the way they do; they are not purely the result of musically inspired directives. Financial strictures don’t determine a melody, the lyrics, or harmony, but they do affect how a record is recorded, and therefore what it ultimately sounds like.

146 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

For

Fear of Music

, the next Talking Heads album, we worked with Eno again. We decided to take our comfort level one step further: we recorded all the basic tracks (the four of us playing together, without me singing) in the loft where we rehearsed, which was also where Chris Frantz and Tina Wey-mouth lived. We hired one of those mobile recording studios that are used to record live concerts and sporting events, and parked it outside on the street, stringing the various cables through the window.A, B

I’m not sure why, but it sounded far better than the messy lo-fi sound one

would expect from recording outside of the pristine studio environment. We

were finally beginning to capture what we sounded like live! Stepping outside of the acoustically isolated recording-studio environment wasn’t, it turned

out, as catastrophic as it was made to sound. Hmmm. Maybe those rules of

recording weren’t as true as we thought.

This wasn’t the only way our recording process had changed. We also

recorded some basic tracks for songs that I hadn’t written words to yet, and later we altered and supplemented some of the sounds of the instruments

well after they had been recorded; some now-familiar arrangements were

actually created after the performance. Recording songs that were “incom-

plete” was risky for me. I wondered, could I really create a song by sing-

ing over prerecorded riffs and chord changes? In some cases I did so quite

successfully (“Life During Wartime”), but other tracks never got finished

(“Dancing for Money”). But succeeding even half the time meant that this

was indeed a feasible working method. I knew that in the future this meant

I might be able to write words that responded to and were guided by pre-

recorded music, instead of getting all bent out of shape trying to get the

music to fit—not just melodically, but sonically and texturally—prewritten

lyrics. Others do this all the time now. St. Vincent (Annie Clark) went into the studio to do her second record,

Actor

, with no complete “songs” written;

A

B

she had only musical fragments. You wouldn’t know this immediately from

listening to her records, but it can be evident when others write their vocal melody over a sample of someone else’s song. In those instances, you know

that the music existed years before the new song was written. The author-

ship is dislocated in such cases, both temporally and spatially. There can be no illusion that the music and lyrics were conceived together. Sometimes

the writer of the music and the writer of the lyrics never meet.

Eno was the one who encouraged us to mess with the sounds after they

were recorded. He’d done a little of that on our previous record, but now

the gloves were off. The furthest we went was on the song “Drugs.” We had

initially recorded a fairly straightforward backing track that seemed a bit

conventional, so we began to mute some of the instruments, sometimes just

silencing specific notes. This made some parts open up; there were more

gaps, more air. I had a recording of koalas that I’d made while we were on

tour in Australia (they mainly grunt and snort, in contrast to their cutesy

appearance), and that got added in here and there. The grunts worked like

indeterminate animal answers and echoes to my singing. More sounds went

on—an arc-like melody created using an echo machine, and then a guitar

solo at the end that was made by selecting fragments from a number of

improvised solos. Finally, I sang the song after jogging in the studio, because for some reason I wanted to sound out of breath. Of course, I was singing the same words and melody as I had been on the earlier, straighter, version of

the song, but now to a vastly altered musical track—a fact that also affected how I sang. The song, as it was released, was an arrangement of sounds that

one would never have come up with in rehearsal or by sitting writing with

a guitar. It could only have been created in a studio. As Eno observed at the time, the recording studio was now a compositional tool.

IMAGINARY FIELD RECORDINGS

(MY LIFE IN THE BUSH OF GHOSTS) 1980

Around this time, Eno and I were listening to a lot of the beautiful record-

ings released on the French Ocora label.C Some of these were typical field

recordings, similar to the ones Alan Lomax had collected in the United States: they were often made with one mic and a portable recorder and featured

148 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

African guys playing rocks, Pygmies singing their intricate hocketing songs, and Muslim calls to prayer. Other Ocora releases were recorded in more controlled situations: in concert halls, churches, temples, and maybe even a few studios. There were Georgian choirs, classical Indian musicians, Iranian traditional music, and North African griots, or praise singers.