How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (50 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

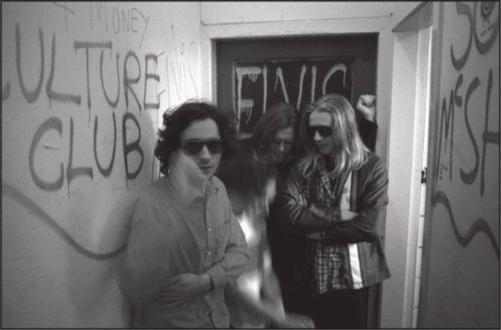

Teenage Fanclub outside their Motherwell rehearsal room where they wrote

Bandwagonesque

, 1991 (

photograph by Sharon Fitzgerald used by kind permission of the photographer

)

C

reation had avoided being affected by the collapse of Rough Trade by changing its distribution to Pinnacle. McGee had been waiting for an opportunity to leave Rough Trade since

Upside Down

. When Kimpton-Howe took over at Collier Street, McGee and Kyllo went to Kimpton-Howe’s former boss, Steve Mason at Pinnacle, to inform him that Creation would soon be in a position to move and would be willing to listen to what Pinnacle had to offer. Creation’s finances were in no better health than Rough Trade’s, as the auditors moved in on Seven Sisters Road in the spring of 1991; Creation was itself weeks away from bankruptcy. All McGee’s hopes were resting on two records on its autumn release schedule: the much delayed and as yet untitled My Bloody Valentine album and

Screamadelica

by Primal Scream.

Screamadelica

’s genesis lay in the band’s encounters with the free-thinking experiments of acid house, as McGee and Jeff Barrett had continued to make connections with the scene’s leading evangelists and DJs. ‘It sort of seemed like shit was possible,’ says Barrett. ‘Seemingly different musical cultures coming together. It was really exciting for me as an indie guy going to acid house clubs, meeting new people and trading ideas. I remember there being so much optimism in the ether, as it were.’

Barrett had left Creation and gone into partnership with a friend, Martin Kelly, to form a new label, Heavenly. The label’s

first three releases were testament to the sense of possibility abroad at the beginning of new decade: an acid house club track by Sly and Lovechild, a Neil Young cover by St Etienne and ‘Motown Junk’, a righteous song of Welsh Valleys indignation by Manic Street Preachers. ‘The Manics is the most flak that we’d ever had for any band that we’ve signed,’ says Kelly. ‘I really remember it being quite vehement but enjoying the fact. I used to get calls from McGee going, “Fucking Manics, man? What have you done? You’ve signed a fucking dodgy punk band. It’s all about acid house now.”’

Kelly had gone to work at Creation for a few months and acted as a bridge between Barrett, McGee and Primal Scream as

Screamadelica

was gradually being made. ‘We were seen as being at the epicentre of something,’ says Barrett. ‘We were the guys who’d worked for Factory and Creation who also took pills with the

Boy’s Own

lot. We were the crossover guys. We were the blah blah. Everybody said, “Why the fuck have they signed a fucking punk rock group?”’ After a second single for Heavenly the Manics signed with CBS imprint Columbia and, in an act of almost unheard-of generosity, reimbursed Heavenly for the expenses they had incurred. ‘They said, “Right, the deal’s done and we’re going to give you the money back,”’ says Barrett, ‘“and we’re going to give you a point on the record.” I hadn’t got a clue what that meant and a cheque arrived for ten grand, which had never been discussed or anything. James Bradfield’s a very generous person and it was a moving and touching thing, and I’d been surrounded by Alan, for one, calling everyone and everything in the industry a cunt, so when something uncunty like that happened, it was very nice.’

The biggest, if not the only, fan of the Manics within the wider Creation circle was Andrew Weatherall, whom Barrett had met DJing in the upstairs room at Shoom and at Future,

where Weatherall had played a filters-off mix of anything he thought would suit the mood. ‘Me and Andrew pretty much hit it off straight away,’ says Barrett. ‘We just hung out a lot and one thing led to another. I took the Scream guys out down to Future … Future was a good club. Andrew Innes liked it there and they all met Weatherall, and boom, boom.’

One evening in late 1990 Barrett, Kelly, McGee and Bobby Gillespie went to see St Etienne and Manic Street Preachers play in Birmingham. Backstage the entourage were introduced to the concert’s promoter, Tim Abbott. A quick-witted and gregarious raconteur, Abbott reminded St Etienne’s Bob Stanley of David Essex, and the Creation/Heavenly party accepted an invitation to repair back to Abbott’s house for an extended aftershow.

‘I had Martin Kelly and Jeff round at our house in Birmingham,’ says Abbott. ‘Did my bond with Bobby Gillespie, “Let’s drink some goat’s blood,” and Alan and Bobby went through my record collection. Me and Alan got on to this big, deep chat about black and white music, linear dance grooves versus structured verse chorus verse, and he said, “Well, what do you do?” and I said, “I’m a marketing consultant. I work for blue-chip companies. I promote a house club. I’m a bon viveur,” and he says, “Great, man, what’s consultancy?” And I said, “Oh, you know, I’m a fucking hired gun, you know, I’ll come into a company …” like, necking Es, and he said, “Well, come down.”’

Whatever his levels of intoxication or stimulation, McGee was also becoming immersed in the role of rock ’n’ roll mogul. Creation was totally reliant on his ability to fast-talk the American major labels into giving him advances on the US rights for future releases; while his Glaswegian burr was rendered occasionally incomprehensible by the jetlag and the drugs, his arm-waving body language meant McGee was starting to be taken seriously by the American labels, who recognised one of their own in his

hunger for success and reward. While hustling and negotiating in America, McGee had also learnt to talk the language of the industry. ‘I remember that night in Birmingham,’ says Barrett, ‘sitting there, pilled out of my mind, and he’d be like, “Barrett, market share’s fucking better than it was a week ago.”’

To Tim Abbott, who was well versed in the manager-class language of market share, presentational skills and targets, the identity of the effusive red-haired companion of Bobby Gillespie rifling through his records was a mystery. ‘I hadn’t got a clue who he was,’ he says. ‘I knew who Bob was, ’cause of

Psychocandy

. I said, “What do you do, then?” He went, “I’ve got a record company,” and I said, “Well – what do you turn over?” and he said, “Just under a million pounds,” and I said, “Well, that’s not bad. It’s great you’re doing what you love. How many do you employ?” and he said, “Well, fifteen sometimes,” and I went, “That’s far too high, but anyway, great, I’ll come down,” and I put on my day-wear and went down to Westgate Street. The big Turkish dude Oz was there on the door, thinking I’d come to buy some gear.’

Stepping into what he assumed might be a record company run along the lines of a service-sector small business, Abbott was astonished to see the warren of offices staffed by an indeterminate group of employees and hangers-on. Abbott was escorted down into the bunker, where he found Green and McGee ensconced in their own nerve centre, a space where Green’s nerves in particular had been tested by My Bloody Valentine’s

Loveless

and its protracted recording and release. ‘I got in there,’ says Abbott, ‘and Alan’s there – like, “Alreet man, alreet.” It was like … fucking hell!’

The gestation of

Loveless

had been a long, painfully drawn-out process of aborted sessions, a never-ending series of mid-range studios and worsening relations between the band and label, particularly Shields and McGee. It had been a morale-draining

period at Westgate Street, especially for a company that had grown used, in its penury, to running on the cheerleading euphoria of McGee. Green and James Kyllo had monitored the recording’s spiralling budget as a trail of invoices from abandoned recording sessions passed across their desks. ‘Week after week we’d be having to find a new studio somewhere that they hadn’t rejected, or [where they’d] found an inaudible frequency or something,’ says Kyllo. ‘They’d stay in a new studio for a while and nothing would happen.’

The myths associated with

Loveless

, that Shields had had a Brian Wilson-style breakdown, that the record’s recording costs were over a quarter of a million pounds, and that they all but rendered Creation insolvent, made great copy. Upon its release the record was rightly heralded as an extraordinary and

ground-breaking

achievement, and the sense of the against-the-odds perfectionism of Shields added to the drama. The reality was more straightforward. While the studio bills for

Loveless

certainly added to Creation’s problems, the label was already bordering on insolvency, but nevertheless the sales of

Loveless

were healthy. ‘If you look at the amount spent over what it actually sold, we probably made a profit in the end,’ says Kyllo, ‘but in terms of what we had and what we were able to do, it was very draining for everybody.’

Aside from the constant anxiety about the scale of the record’s costs and the interminable delays, a significant factor counted in Shields’s favour. However much bad blood there would be after its release, and whatever the intemperate language used to describe

Loveless

later, nevertheless, when the tapes were finally delivered, they were treated with reverence at Westgate Street. ‘We kept going with what they wanted,’ says Kyllo. ‘What else could we do? We knew we needed that record and we did think at the time, and Alan certainly did, that Kevin was a genius.’

As well as Ride, there were other bands signed to Creation who shared the view that Shields was the innovative and visionary auteur of his generation. Both Slowdive and the Telescopes had released records on the label that had partially filled the demand for My Bloody Valentine in their absence. ‘I don’t know if any of those groups broke even,’ says Kyllo, ‘but they were a very worthwhile second string, and we felt that we were surfing the

zeitgeist

and we were putting out the best records of the time.’

However much Creation felt it was at the heart of the culture its finances remained desperate. In the hangdog environs of Hackney, and in the middle of a recession, McGee at least felt at home. ‘The bank on Mare Street got robbed so many times,’ says McGee. ‘I’d come off a tour and needed to put some cash in and taken the Abbott with me for protection. These guys in a car rolled down the window and went, “Don’t fucking bank there, we’re robbing it Monday!” and they weren’t taking the fucking piss – every week that bank got robbed. They had to shut it down.’

It was a miracle that Creation continued to escape the same fate. An endless stream of creditors were ringing the offices for settlement on long overdue invoices or sending written

confirmation

that matters were now in the hands of their solicitors. ‘We were trying to keep some accounts going just by paying the very bare minimum of what we owed,’ says Kyllo. Tim Abbott had carried out an evaluation of Creation in his own inimitable style, which had included a hands-on audit of the various drug dealers that visited Westgate Street for comparison and appraisal. As Abbott and McGee became deeper and druggier friends, Abbott was impressed by McGee’s day-to-day ability to focus on keeping the company afloat but he had yet to uncover a long-term strategy. ‘Alan’s commitment to work rate was quite amazing,’ says Abbott, ‘but as for the future it was just, chuck enough in the air and assume it would always be OK. There was no planning whatsoever.’

In an attempt to reposition Creation in a more inclusive context within the rest of the industry, Abbott concentrated on developing a relationship with Creation’s distribution company, Pinnacle. ‘On my first consultancy with Alan I said, “Tell me about your sales team,” and he went, “They’re cunts,” and I said, “Oh, that’s empowering, then.”’

Creation had high hopes for

Giant Step

s

the forthcoming album by the Boo Radleys. The record, a deliberate mix of studio-

as-instrument

experimentation and pop-song craft, was trailed by a hook-laden single, ‘Lazarus’, which Creation had thought would breach the Top Forty. Abbott devised a campaign for

Giant Steps

, including Creation’s first marketing plan, which saw the band scrubbed up in suits and a lengthy series of advertising that ran long past the record’s release date. Pinnacle were informed that

Giant Steps

was the label’s priority and they were to be given all the necessary tools, including a re-release of ‘Lazarus’, to ensure that

Giant Steps

was a crossover success.

‘I said to Alan, “I’m taking you down to Pinnacle,”’ says Abbott. ‘“I’m going to brush you off right, and you’re going to shake everybody’s hands and I’m going to say, ‘This is the great god, Alan McGee of indie records,’ and they’re going to meet you and realise that you’re human.” He said, “D’you think that will work?” and it’s like, if it was fucking hairbrushes we were selling, and you were the king of the bristles … so all of a sudden, it changed his whole perception.’

There was another significant change at the Creation offices: the more hard-edged peaks of cocaine had replaced the euphoric highs of Ecstasy. While the drug provided a

backed-into

-a-corner focus for McGee, it also meant his mood swings, already amplified by the relentless stress of perpetual near bankruptcy, were becoming more volatile. ‘Coming out of the house scene, everybody switched to cocaine,’ says Abbott. ‘Alan,

as he was on E, became very much an obsessive on it. I think he got a bit blurred on it. It became a way for him to deal with his impatience.’

In a sign that Creation had at least decided to become a little more professional, Dave Barker had taken over what had been the Ecstasy party room and set up an office. His A&R brief was to be himself, which often largely consisted of him playing excellent records while fielding calls from whichever of his many Glaswegian friends had started a band that week.

‘There was a few parties went on,’ says Barker, ‘but people weren’t off their nut all day long. They fuckin’ worked hard. Occasionally the tannoy would crank up, “Everybody get down the old bunker, we’re gonna have a party.” And you’d go down there and Alan’s got all these bottles of champagne, there’s lines of Charlie chopped out and fuckin’ Es and stuff, and everyone’s getting into it.’

Barker’s links with Teenage Fanclub and Eugenius ensured Creation had high cultural capital in the States, where few British bands were considered part of the prevailing musical trends. In turn McGee had signed Sugar, Bob Mould’s perfectly timed return to power-trio dynamics, which gave Creation a great cachet – and healthy sales – in the post-

Nevermind

landscape. ‘The Fanclub/Nirvana link with Sub Pop and everything meant we were deemed as extremely cool in the States,’ says Abbott. ‘The likes of Slowdive and all that were gone, dead.’