How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (58 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

*

One of the tour’s most celebrated concerts was at Newport TJs. A recording of the banter between the audience members and bands was eventually released on vinyl. One memorable heckle aimed at Huggy Bear includes the repeated phrase ‘less structure, less structure’.

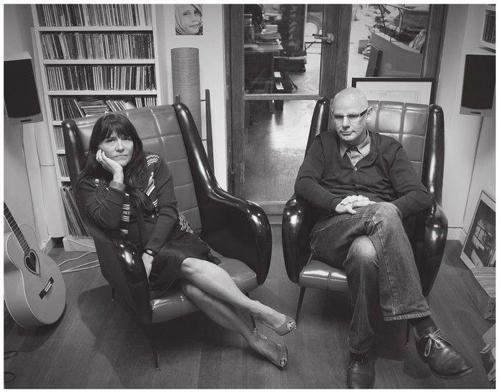

Jeannette Lee and Geoff Travis in the offices of Rough Trade (

photograph by Rob Murray used by kind permission of the photographer

)

‘

C

hampagne Supernova’, the final song on Oasis’s second album

What’s The Story (Morning Glory)?

contained the lyric, ‘Where were you when we were getting high?’ It could have been directed to Alan McGee, who had been almost entirely absent from the band’s tumultuous ascendancy. After a

year-long

period of recovery and convalescence McGee reacquainted himself with the label, which had moved to newly acquired offices, a converted school building in the salubrious Primrose Hill, a location that suited Creation’s rising profile as Britain’s most successful record company.

To long-term employees, it seemed that McGee had weathered his problems with alcohol and drugs reasonably well. In his sobriety he had a new-found relish in the more mundane and technical aspects of the company; the drug-fuelled talk of a band on Creation selling a million was now, thanks to Oasis,

stone-cold

sober fact. ‘I think, in some ways Alan returned and enjoyed himself with more satisfaction,’ says James Kyllo. ‘It was a very, very dynamic time, so much had to be dealt with and our release schedule got very heavy, especially after Oasis.’

McGee also found he was the head of a company that had shifted its emphasis. Creation’s principal marketing device had consisted of providing vicarious rock ’n’ roll thrills and

guest-list

places for journalists, record-store buyers and distribution companies. Tim Abbott had harnessed such devil-may-care amateurism into an aspirational and inclusive USP for Oasis;

the rest of Creation’s roster would now benefit from the cold and exact science of competitive, target-led, High Street marketing. Creation released three singles from Teenage Fanclub’s

Grand Prix

. Each one was accorded a budget of £100,000 to enable a guaranteed Top Twenty chart position. Before the additional costs of promoting and marketing the album were considered, Creation were spending more on each of

Grand Prix

’s singles than the band had spent on recording their last two albums.

Upon his return McGee embraced something of a portfolio career. As well as being MD of Creation he was now advising New Labour on its Creative Industries strategy and the party’s rather vague ideas about engagement with young people. While in recovery, McGee had rediscovered his childhood love of Rangers. As football became a key signifier of the period, McGee’s renewed interest in the game was focused on Chelsea, where he and Ed Ball took up their positions in a box every Saturday.

*

As a man now in demand in the broadsheets and business press – where he was usually profiled as Mr Oasis – his opinion was regularly sought and he became something of a celebrity. Behind the smartened-up high-flyer executive image, flashes of the former, quixotic, McGee still surfaced. In 1997 he and Ed Ball made a drum-and-bass LP.

The Creation tradition of hangers-on was maintained, along with the ritual of finding jobs for the boys and the girls. The new, user-friendly Creation drew its support staff from a different set of characters from those with which it had once partied hard. Rather than drug dealers and club promoters, Creation now offered short-term employment to associates of the era’s rising

celebrity class. ‘Ed Ball gave up Chelsea when they sacked Vialli,’ says Kyllo, ‘but we had Chelsea footballers come to the Primrose Hill office and Alan would take them round the warehouse and hand out CDs to them. We even had a Chelsea footballer’s girlfriend join the staff at one point.’

Whatever his own lifestyle regime, McGee was aware that some of the rock ’n’ roll behaviour that had made Westgate Street’s reputation had survived the move to Creation’s new offices. ‘They had orgies in Primrose Hill apparently,’ he says, ‘but they were all too scared of me and I was never invited.’

A consequence of Oasis’s unprecedented success was that Creation became heavy with bands beholden to their sound and image, most notably Heavy Stereo and Hurricane #1. For a label that was now marketing-led and experiencing era-defining volumes of sales, such bands were duly expected to succeed. While no one at Creation was anticipating Heavy Stereo or Hurricane #1 to reach the sales heights of Oasis, the bands were duly processed through the marketing machine at Primrose Hill, all to very little effect.

Mark Bowen had been brought up in the hand-to-mouth culture of pre-Sony Creation and was now the label’s A&R. The change in the label’s climate provoked the odd moment of culture shock. Creation was now a highly staffed operation and one that had adjusted to the requirements of the Top Ten market. ‘There was probably a point in about ’98,’ he says, ‘where for the first time I’d go and see a band and think, this is amazing, I love it, but obviously it’s not so good for Creation.’

The rest of the industry was equally well positioned to sell guitar bands, as the second or third wave of Britpop saw

major-label

A&Rs stick rigidly to the formula and sign up anyone playing Camden who exhibited the necessary hallmarks of braggadocio and a retro guitar. ‘Suddenly you’d go to the Falcon or the Dublin

Castle,’ says Bowen, ‘and there’s basically a load of blokes with their metaphorical chequebooks out. You’re watching the same band and thinking, whether good or bad, these are bands that would’ve signed to indies, and made records, and suddenly, before they’d made a demo or done three shows, they were signed to major labels and off you go.’

Bowen ignored the Camden hopefuls and signed a group that was in the experimental-melodic tradition of Creation’s early Nineties vintage: Super Furry Animals, a Welsh band based in Cardiff. ‘It was pretty old-school Creation in how it all happened,’ he says. ‘The demos were amazing and Alan didn’t care that they’d sing in Welsh. He was very supportive. Later on it was Alan who insisted that we put out “The Man Don’t Give a Fuck” as an A-side.’

Bowen’s experience of the Welsh language punk scene of the late Eighties, when bands like Datblygu and Y Cruff mixed nationalist politics with a ferocious, angry, noise, was a cultural heritage he shared with the band. ‘These were people my age with my background,’ he says. ‘Slightly different, given that they were north Wales and Welsh-speaking and I was from Cardiff, but they had been Mary Chain tribute bands singing in Welsh, growing up they had been as obsessed with Creation, as I was.’

Behind the monolith of brand Oasis, Creation’s release schedule started to reveal hints that McGee had refamiliarised himself with some of his impetuous and mischievous tendencies. Along with encouraging and financing Super Furry Animals’ purchase of a tank, he had used Oasis’s money to finance releases by Nick Heyward and offered the Sex Pistols’ bassist Glen Matlock a deal. Some of the Creation old guard were also encouraged to enjoy themselves. At any given point Ed Ball had at least two records in production; he even reconvened his pre-Television Personalities band, the Teenage Filmstars, for an

album. Joe Foster returned from the wilderness and a mooted Slaughter Joe LP was pencilled in for release. Most improbably of all, Pat Fish, the Jazz Butcher, started a new project, Sumosonic, that explored keyboards and techno rhythms. Sumosonic’s

line-up

consisted of Fish and three female models.

†

McGee was no longer as close as he had been to Primal Scream; the differences in their lifestyle made it all but impossible for him to spend any kind of time in their company. The band had been through similar highs and lows of the kind that had damaged McGee, and had developed a bunker mentality from which they regrouped to release the album

Vanishing Point

in 1997. A dense and brooding record, it punctured the death throes of Britpop with a sense of anger and dread. In true Primal Scream fashion a rather heavy-handed and curatorial referencing accompanied its release. The album artwork was designed to the exact specification of the house style of the reggae label Blood and Fire, and the album’s second single, ‘Star’, featured a photograph of a Black Panther on its cover. If a little incongruous, it provided light relief from the succession of cagoule-wearing likely lads filling up the racks in HMV.

However much he enjoyed the limelight and Creation’s worldwide reputation, McGee was growing listless. When Oasis played to the multitude at Knebworth for two nights, in his heart of hearts he registered that the moment had peaked. ‘I love rock ’n’ roll,’ he says, ‘but there’s a point, even with me, when Oasis were getting into helicopters at Knebworth and it was a 125,000-crowd giggle. That was the point that I thought, exit, and I didn’t have the balls to do it; and I should’ve done it then. It

would have been a better statement to end it at Knebworth, and let them just start their own record company after that.’

Instead one of his next signings would prove to be one of Creation’s most controversial. Kevin Rowland had endured some painful moments and wilderness years after the million-selling career of Dexys Midnight Runners. Having been in and out of recovery, he was ready to make a new record and McGee had no hesitation in wanting to work with one of his heroes. Rowland recorded an LP of cover versions, whose lyrics he altered to make them more autobiographical and reflect the experiences he had undergone. Entitled

My Beauty

, the record featured some soaring performances from Rowland that were equal to the best of his Dexys work.

My Beauty

should have found a willing audience, one that wanted to welcome a returning hero who had found salvation in a set of poignant life-affirming songs. Along with finding meaning in material that he had first heard as a teenager, Rowland had also taken to wearing a ‘man-dress’, a costume to which he occasionally added jewellery and

make-up

, something he did for the album’s sleeve, which featured the singer in a purple frock.

In more enlightened times, the gesture might have been considered a further example of Rowland’s eccentricities. The singer had often changed his appearance – Dexys Midnight Runners had variously dressed as dockers, gypsies and Wall Street preppies, but at the height of the

Loaded

era, the majority of his original fans found his new wardrobe shocking.

The video for the album’s single, ‘Concrete and Clay’, was also far from straightforward. In between close-ups of Rowland’s stockinged thighs, it featured the singer gyrating provocatively with exotic dancers, as backing singers, dressed as angels, cooed approvingly.

Creation’s marketing expertise and budgets ensured that the

image of a cross-dressing Rowland was fly-posted across the country, something that, rather than promoting the album, guaranteed it almost certain death. ‘If it hadn’t been for the cover with Kevin in a sarong then the bottom line is it would’ve hit the Radio 2 audiences,’ says McGee. ‘It’s an amazing record. But you know what, Kevin was Kevin and there’s nobody can tell Kevin what to do. People thought I’d put him up to it!’

Another factor was playing on McGee’s mind. Without any common purpose or enemy to fight for or against, he had, in its smooth-running success, grown increasingly bored of the label and had mentally begun to wind Creation down. ‘I was left with two choices with

My Beauty

’, he says. ‘Put it out like that or don’t. It was the end of Creation anyway. I was really at the end of it, phoning up Dick and saying, “Fucking hell, I’ve just got so fed up with this label,” and I think it was like a breath of fresh air for him to actually tell the truth finally: “I’ve been fed up for years, Alan, and I’ve been waiting for you to tell me that you couldn’t be bothered any more.”’

As McGee started examining the paperwork of the Sony/Creation deal to assess the ramifications of closing the company down, it also became apparent that the label might end on a high. Primal Scream had recorded a new album,

XTRMNTR

, that not only matched the creative peak of

Screamadelica

, it was its menacing, nihilistic animus.

Jeff Barrett had always been involved with Primal Scream, either formally or informally, or usually both. He was significantly involved in

XTRMNTR

as he helped supervise the release in the absence of Creation’s MDs, who were distracted by the winding-down process, as Sony, McGee, Green and their lawyers negotiated a settlement. ‘Bobby [Gillespie]’s really upset that we weren’t around for

XTRMNTR

, which is fair enough,’ says McGee, ‘but I couldn’t stand Sony. Sony realised that on our

overhead they could actually save half a million by letting us go six months early and at that point I was like fucking off the roof, man, “Come on!”’

XTRMNTR

was Creation’s last album and its last masterpiece. After a long succession of half-baked, marketing-heavy records, the label had returned to its roots and released a record of energised, mercurial rock ’n’ roll. As well as featuring one of Kevin Shields’s finest guitar lines, the closing track, ‘Shoot Speed/Kill Light’ reintroduced the word ‘speed’ into the Creation lexicon. During its early, folded-sleeve years, speed had been Creation’s key signifier and featured in many of its song titles. On its final release the label was once more celebrating velocity.

McGee encountered no little degree of rancour at his decision to close Creation. Primal Scream especially, the band whose members he had known since their teens and been the label’s hallmark, felt abandoned. ‘I never said it was for life. I never said I was going to be Primal Scream’s dad,’ he says, ‘and you know what, I’m not perfect and maybe I did leave at a really rotten time for them in particular, and, you know what, I apologise. I fucked off, and people got pissed off. But this is where people don’t understand me, I don’t care about indie music, and it’s not because I think I’m better than indie music, it was a means to an end.’

Away from the fall-out of the label’s demise Dick Green had quietly approached Bowen about the possibility of doing something together. They had developed a close working relationship separate from the Oasis engine room, one in which they had maintained the label’s rapport with bands that had been signed before the move to Primrose Hill, notably the Boo Radleys and Teenage Fanclub. Green suggested to Bowen that if they were to work together, then the pre-gold-record era of Creation, for which Green held the most affection, should be

their inspiration. ‘Dick was sat there and said, “Look, I’d really like to do another label,”’ says Bowen, ‘“but it’d be really totally different to what we’re doing: no staff, no office, just real back to basics, start again, start right at the beginning, get away from all this,” and I didn’t even have to think twice.’