Read How the French Invented Love Online

Authors: Marilyn Yalom

How the French Invented Love (16 page)

At the beginning of the book, the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, once lovers, remain friends who share a common agenda: to indulge their erotic appetites through successive affairs but never to fall in love. Both think of these affairs as conquests and, following the military vocabulary that informs their speech, they must always be the ones who decide when to invade, when to withdraw, and when to seek revenge. Madame de Merteuil’s desire for revenge sets the plot in motion. She enlists Valmont to seduce the young Cécile, who has been promised by her family to the Comte de Gercourt, one of the Marquise’s former lovers. Because Gercourt had left Madame de Merteuil for another mistress, she will not be satisfied until he finds himself with a thoroughly debauched bride.

But Valmont has his own program. When he receives his orders from the Marquise to seduce Cécile, he is already in pursuit of Madame de Tourvel, the notoriously chaste wife of a provincial dignitary. Valmont has built his much-envied reputation on the basis of multiple conquests, and he has no intention of flubbing this one. Handsome, endowed with title and fortune, he represents the consummate libertine seducer. The three female characters incarnate various aspects of womanhood. Cécile is a sensuous ingénue, ready to be plucked. Madame de Tourvel is a repressed sentimentalist, also ready to be plucked. Madame de Merteuil is a perverse feminist, in her words to Valmont, “born to avenge my sex and to dominate yours.”

7

Compared to the sublimely virtuous characters in

La nouvelle Héloïse

, the main figures in

Les liaisons dangereuses

are either perpetrators of vice or their victims. The perpetrators—Valmont and Merteuil—are ingeniously cruel, she even more than he. The victims—Cécile, Danceny, and Tourvel—are trusting and gullible. Two of them end up dead, one retires to a convent, another becomes a knight of Malta, and one lives on with disfiguring smallpox and the loss of an eye. You will have to read the book to find out who gets what. Believe me, once you start to read it, you’ll be transfixed till the end.

Yes, I cannot deny it—

Les liaisons dangereuses

is a more compelling work than

La nouvelle Héloïse

. As in Dante’s

Divine Comedy

, which offers better material for the Inferno than for the Paradiso, Laclos’ depiction of evil has an irresistible demonic appeal. In addition, the epistolary style he borrowed from Richardson and Rousseau turns out to be the perfect medium for conveying the relentless progress of Merteuil and Valmont’s infernal strategies. Not a single word is wasted. Everything proceeds with machinelike efficiency. Whatever goodness existed in the fledgling love between Cécile and Danceny, and in Madame de Tourvel’s tender feelings for Valmont, and even in Valmont’s attentions to Madame de Tourvel, will be swept away by gallantry run amok. Laclos’ contemporary, the writer Nicolas Chamfort, succinctly expressed this dissolute and solely materialistic aspect of gallantry in one of his most famous epigrams: “Love, as it exists in society, is only the contact of two epidermises.”

And yet, hidden within

Les liaisons dangereuses

, one finds whispers of Valmont’s love for Madame de Tourvel and even that of the Marquise de Merteuil for Valmont. Ironically, it is this tender love—this love engaging the heart as well as the body—that dares not say its name. Madame de Merteuil spots true love in Valmont’s letters about Madame de Tourvel, and, motivated by jealousy, she forces him to live up to his reputation as a coldhearted seducer. So true love, though still capable of sprouting within a hostile environment, is ultimately crushed by sadistic libertinage.

Having consciously avoided the word “sadistic” up till now, I have intentionally used it here to imply that at least one of the perpetrators—Madame de Merteuil—gets pleasure out of inflicting pain on others. The word “sadism,” meaning a sexual perversion characterized by the enjoyment of cruelty to others, derives specifically from the work of the Marquis de Sade. His novel

Justine

, published in 1791 at the height of the French Revolution, and others that appeared despite his many years in prison and the madhouse, carry the libertinage of Crébillon fils and Laclos to new depths of horror. Sade’s heroines are submitted to verbal abuse, physical torture, rape, and other repugnant forms of violence. His fictional libertines lack guilt and remorse and do not get their just desserts. What, you may be asking, does any of this have to do with love? It’s a good question, one that I pondered when asked by a French friend if I intended to address Sade in this book. My friend insisted that I must do so since Sade understood the link between love and evil better than any other thinker. To admit that I can’t bear to read Sade, that he makes me sick, and that I don’t intend to inflict him on my readers may speak to intellectual cowardice. So be it.

I’ve heard enough personal stories in my life to know that some people, mostly men, get their sexual highs by manipulating, abusing, or beating up on women. Here is one told to me not long ago by a Frenchwoman.

Dominique is a lively lady nearing sixty, well bred, nice looking, divorced, and the mother of two ravishing daughters. Since her divorce, she has worked part-time in a fine jewelry store, where her taste and warmth are much appreciated. I’ve never met a person who seemed happier.

Yet, as I learned recently, Dominique lived a secret horror for almost thirty years. Her husband was a sadistic pervert. He could make love only by humiliating her, insulting her, making her cry, then taking her violently.

On top of that, she discovered fairly early in the marriage that he was bedding anyone else he could lay his hands on, mostly young women working in the company he directed, women wanting to get ahead professionally in return for sexual favors.

Why did Dominique stay in the marriage so long? Her answer: because of the children. She got some satisfaction by taking a lover, who helped restore confidence in herself as a sexual being. Then, with the aid of a

psy

(that’s the French term for a shrink), she ultimately asked for a divorce, at which point her husband ran off with someone the age of their daughters. Dominique still has nightmares about her husband’s sadistic practices, but in the daytime she leads a very active life. No, she is no longer with her former lover, who was offered a job in another country. She would like to find someone else, just a decent man who has normal sexual needs. Still, she considers herself lucky to be rid of a husband who was, in her words, “right out of a novel by the Marquis de Sade.”

T

o schematize the period stretching from the death of Louis XIV in 1715 to the end of the century, I have tried to show how the French repackaged love in two competing brands: libertinage and sentimentalism. The first brand exaggerated the immoral aspects of gallantry, spreading sexual license from the nobility to the middle and lower classes, and to women as well as to men. The fictions of Prévost, Crébillon fils, and Laclos bore witness to the corrosive presence of libertinage in

ancien régime

France. The second brand of love accentuated feeling. Sentiment, emotion, tenderness, passion—these were the hallmarks of a true lover. With Rousseau leading the charge, sentimentalism spread its empire among the entire reading public, starting with the bourgeoisie and extending upward to the nobility and downward to the lower classes. Lawyers and administrators, the wives of merchants and doctors, unmarried governesses and shop girls—all professed devotion to sentimental love.

These four novels reflected the practice of love in prerevolutionary France. And they did more than that: they created new ways of feeling, behaving, and expressing oneself. How many men read and reread the pages in which Versac told them how to conduct themselves so as to seduce as many women as possible and still maintain the reputation of a gentleman? How many parents advised their offspring to read

Manon Lescaut

and

Les liaisons dangereuses

as cautionary tales? How many men and women, reborn as sons and daughters of Saint-Preux and Julie, turned their own lives into epistolary novels? One of the latter group, Julie de Lespinasse, provides an extraordinary example of this interplay between fiction and life, so much so that I’ll devote the next chapter to her alone.

Love Letters

Julie de Lespinasse

I

REGULARLY RECEIVED TWO LETTERS A DAY FROM

F

ONTAINEBLEAU. . . . HE HAD ONLY ONE OCCUPATION, HE HAD ONLY ONE PLEASURE: HE WANTED TO LIVE IN MY THOUGHTS, HE WANTED TO FILL MY LIFE.

Julie de Lespinasse, Letter CXLI, 1775

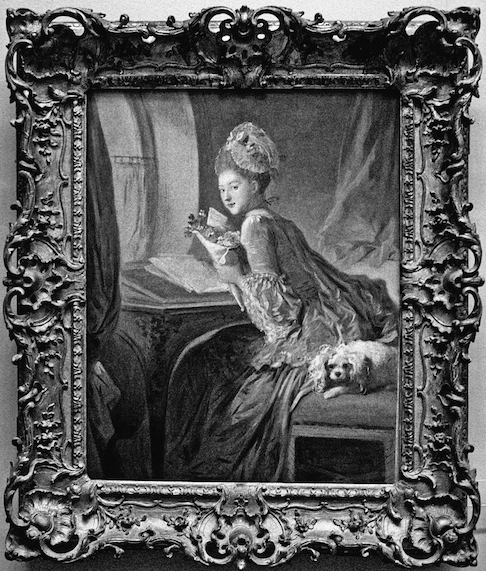

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, “The Love Letter,” circa 1770–1790. Copyright Kathleen Cohen.

J

ulie de Lespinasse thought of herself as the heroine of a novel. She considered the facts of her life more fantastic than the fictions of either Samuel Richardson or Abbé Prévost.

1

While she never wrote her memoirs for public consumption, the hundreds of letters she left behind read like one half of an impassioned epistolary novel.

During her lifetime, letters were the staples of human communication within cities, throughout Europe, and across the seas. What the telephone was to the twentieth century, and email, texting, and tweeting are today, letters were to our ancestors. People stayed in touch with each other on a regular basis, sometimes weekly, biweekly, or daily, and these letters were not just short telegraphic messages. They were well-written and lengthy, containing descriptions of one’s experiences and observations, as well as feelings that might have been awkward to express face-to-face. Within Julie’s Parisian circle, which contained many of the best-known figures of her day, letters were often written so as to be read aloud to others or copied for circulation or saved for posterity.

Love letters constituted a prized category. Would he have the nerve to declare himself in writing? Would she respond with the appropriate dose of encouragement? Would they manage to keep their correspondence free from snooping eyes? How could they endure silences due to illness or distant travel or letters that simply went astray? What should she surmise if he sent letters less frequently than before? If she was approached by another suitor, could she write to the second man as well as the first? Love letters were meant to be treasured, to be read over and over again while passion burned, and again in old age when the fires of youth had cooled. If the affair didn’t turn into a lifetime attachment, the right thing to do was return the letters to their author. People died with love letters stashed away in boxes and desks, leaving instructions in their wills that all their papers should be destroyed. Though most of the love letters written to Julie were indeed burned right after her death, a few others managed to survive; and, above all, the 180 letters she wrote to the Comte de Guibert bear witness to her incredible life story.

2

When Julie de Lespinasse died at the age of forty-four in 1776, she was famous as the muse of the

Encyclopédistes

—d’Alembert, Condorcet, Diderot, and so many other luminaries who had been regulars at her lively salon. For twelve years, the cream of French literary, scientific, and artistic society streamed into her apartment almost every day from five to nine in the evening for the sole pleasure of conversation. Her demise was mourned by Enlightenment leaders from Paris to Prussia. Frederick II sent his condolences to Jean le Rond d’Alembert, and d’Alembert wrote her two intensely moving love letters several weeks after she had died.

Who was d’Alembert and why would he have written to Julie after her death? D’Alembert was a renowned mathematician and philosopher and Diderot’s first collaborator on the

Encyclopédie

—a mammoth dictionary of eighteenth-century knowledge. Between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-five d’Alembert wrote the numerous treatises that would place him in the ranks of the greatest Enlightenment intellectuals: Fontenelle, Montesquieu, Buffon, Diderot, Voltaire, and Rousseau. Nearing forty, he fell in love with Julie, who was fifteen years his junior. For twelve years, from 1764 to 1776, their shared life was a matter of public record. For the sake of form, they lived in separate quarters of the same building, although everyone assumed they were lovers. They probably were for a time, and then they were not. But whatever the exact nature of their relationship during all the years they were together, d’Alembert never stopped loving her and treating her as the exclusive mistress of his heart.

But Julie, after her first years with d’Alembert, was not satisfied with the love of one devoted man, however distinguished. There would be two other lovers during this same period. Somehow she managed to keep the depths of her great passion for the Marquis de Mora hidden from d’Alembert. Similarly, he didn’t know the true nature of her relations with her last lover, the Comte de Guibert.