How They Started (13 page)

Authors: David Lester

“We went from idea to launched product in just over a month,” Andrew says. “And it was a success—25 people had to buy in, and it tipped.”

Encouraged, Andrew tried more deals. But in 2008, Groupons were still a sideline to The Point. Revenue for the year was just $5,000.

For Andrew, a couple of key deals that came shortly afterward demonstrated the potential of Groupons. One was for a stay in a sensory deprivation tank, an offbeat service Andrew was unsure would sell—but it did. Another notable offer was for a $180 tooth-whitening treatment, a much higher price than Andrew had yet tried. When hundreds of people signed up, the team knew Groupons could be a real revenue stream for The Point.

“We realized we’d tapped into this insane demand,” says Eric. “People wanted to go skydiving, try that massage parlor, become a member of the Art Institute, or go on an adventure trip—but they needed something to push them. Groupon was that thing.”

In January 2009, Chief Technology Officer Ken Pelletier threw a late holiday party at his small apartment for the entire The Point staff, their spouses and friends. It would be the last time the company would fit in such a small space.

“People wanted to go skydiving, try that massage parlor, become a member of the Art Institute, or go on an adventure trip—but they needed something to push them. Groupon was that thing.”

It was clear Groupon wasn’t a revenue model for The Point—Groupon

was

the point. The company was reorganized and renamed that month, with Brad serving as a director. One year later, Groupon would have 300 employees. The year after that, Groupon would have a staff of 5,000.

Chicago clearly loved Groupon, snapping up $100,000 worth of deals in the first quarter of 2009. It was time to test Groupon deals in another market to see if Groupon would work beyond the founders’ home turf. The second Groupon market, Boston, opened in March.

Any doubts about the business model were quickly laid to rest. Boston took off just as Chicago had. Everyone realized Groupon wasn’t just a good local money-making idea—it was a huge, global idea.

As it happened, Groupon’s timing was perfect—the economy had just gone into the tank, and bargains were hot. Bloggers raved, the mainstream media took note, and a media honeymoon began that would boost the company’s early expansion efforts.

Corporate missives were often playful, as in a blog post noting that the black background of the Groupon logo “symbolizes the constant darkness that would plague a world bereft of daily deals.”

After Boston’s success, board members urged Groupon to expand as fast as possible, fundraising aggressively to pay for staff and online advertising. Groupon needed to build brand recognition and acquire scale to operate efficiently. Also, the barrier to entry for daily deals was fairly low. Competitors would be coming soon, NEA’s Weller forecast—and in fact one of Groupon’s most successful competitors, Living Social, launched that year.

Groupon quickly added New York, San Francisco and Washington, DC, and second-quarter revenue shot to $1.2 million. Another dozen markets were opened in the third quarter, the subscriber base grew to 600,000, and sales leapt to $4 million. The pace continued in the fourth quarter, with another 13 markets opening. Groupon would close out the year with a total of $14.5 million in revenue.

The company was a venture capitalist’s dream: an almost endlessly replicable model that promised good profit margins once each market was established. At year-end, the company raised nearly $30 million from Accel Partners and NEA to fuel yet more growth.

As it grew, Groupon asserted a fun, wacky corporate personality. The company hired squadrons of copywriters to create amusing ad copy for the deals. Corporate missives were often playful, as in a blog post noting that the black background of the Groupon logo “symbolizes the constant darkness that would plague a world bereft of daily deals.”

Beneath the levity, growing like a weed taxed the limits of Groupon’s executive team. Ostensibly an investor, Eric found himself sucked into the day-to-day operations, reporting on his blog that he served as de facto chief financial officer for nearly a year until Jason Child was hired at the end of 2010.

One big problem was employee pay. The sales staff was on a commission program initially premised on modest sales. Instead, some Groupon offers sold in the thousands, and salespeople could earn as much as $300,000 a year. This enraged some salaried support staff, many of whom were working long hours as well. After one staffer sued for equitable pay, some raises were given.

On the tech side, the company was constantly scrambling to bring on enough talent. Andrew says his biggest mistake was not opening a branch office in Silicon Valley until 2010. Chicago was not a tech hub, and it was hard to lure Californians to the Midwest.

By 2010, more than 2,500 merchants had participated in Groupon deals. As each market could only do 365 offers a year, most cities had long waiting lists. While the majority of merchants were happy and often signed up again, a distinct minority were displeased.

Reports surfaced of merchants who lost money after offering a Groupon. In a widely circulated blog post, Posies Café owner Jessie Burke in Portland, Oregon, said she had to pay $8,000 in payroll out of savings after throngs of customers bought her half-price Groupon deal, which was a money-loser.

In a Rice University study, 40 percent of Groupon merchants said they wouldn’t do another offer. Groupon countered that the vast majority of merchants were happy, and the number of participating merchants continued to climb. It became clear that offers needed to be carefully structured, though, to avoid burning the merchant.

In 2010, Groupon continued its stiff pace of entering new US markets, adding 13 more in the first quarter alone. The company began acquiring small competitors to add more markets quickly, along with tech companies to build out the platform. But the year’s defining event was the acquisition of CityDeal, for a reported $100 million.

Forbes magazine would proclaim Groupon “the fastest-growing company … ever.”

Overnight, Groupon was a global brand, adding major European markets including London and Berlin. Groupon was able to scale these markets at a breathtaking pace, taking the London market from $1.7 million to $27 million in revenue just over a year later, for example. Masterminding much of the overseas expansion were CityDeal’s owners, brothers Marc, Oliver and Alexander Samwer, savvy Germans with a history of creating acquisition-worthy European clones of US companies.

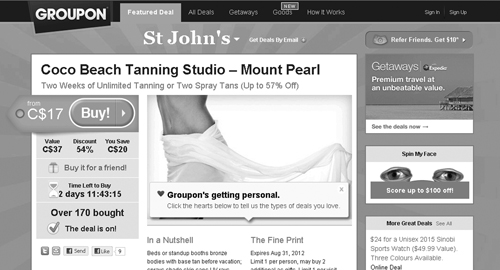

A screenshot of Groupon’s website today.

In all, Groupon entered 45 new countries in 16 months flat, a boggling feat. Eighty markets were added in the second quarter alone, taking Groupon from zero to more than $100 million in overseas business in 2010. Investors liked what they saw. In April, Groupon raised $135 million, from Accel, NEA, Battery Ventures, and Russian tech mogul Yuri Milner’s Digital Sky Technologies. In August,

Forbes

magazine would proclaim Groupon “the fastest-growing company … ever.”

Besides its overseas expansion, Groupon broke new ground by offering its first national deal. An offer for $50 worth of clothes for $25 from apparel chain Gap sold 433,000 Groupons for $10.8 million. The Gap deal generated tons of press, and better yet, 200,000 new subscribers.

With small imitators springing up in many cities, Groupon differentiated itself by introducing a “Preferences” feature, enabling subscribers to receive offers in categories of interest only. The company also introduced a Groupon Rewards program, in which customers earn more discounts by shopping a merchant more frequently.

By now, Groupon had grown successful enough to attract not just media attention, imitators, and investors, but also buyout offers. But the team wasn’t keen to sell, preferring to continue growing the company themselves.

In mid-2010, Yahoo! made an offer rumored to be between $3 billion and $4 billion, only to be quickly rebuffed. The struggling search engine had its own problems, and the Groupon team wasn’t interested in an alliance.

The next offer was harder to turn down. It was from Google, for a whopping $5.75 billion. But reports were that antitrust concerns shot the deal down. Instead, Groupon turned to private-equity investors again, raising $450 million at the end of the year, which dwarfed 2010’s $313 million in revenue.

The funds kept flowing in, with Groupon raising another $492.5 million in early 2011. Interest from funders grew as the inevitable next step for the fast-growing phenomenon neared: a public offering.

As the company prepped its IPO in early 2011, the executive team seemed to crack under the strain. First, President and Chief Operating Officer Robert Solomon quit in March after one year, followed by founding CTO Pelletier, who cited exhaustion. His replacement, former Google executive Margo Georgiadis, lasted only a few months. One communications head, Bradford Williams, lasted just two months. The C-suite turnover foreshadowed the rough waters ahead.

After Groupon filed its IPO papers in June 2011, the company was criticized for both the form and content of its filing. It used unconventional financial-reporting methods, prompting restatement requests from the SEC. Eric and Andrew made statements that leaked to the media and were viewed as potential violations of SEC “quiet period” rules. An aura of suspicion enveloped the company.

Groupon’s restated figures showed $1.1 billion in revenue for the first three quarters of 2011 and a $214.5 million loss—a surprise, as Andrew had said Groupon was profitable the prior year. Also news: over $940 million of the $1.2 billion in venture capital Groupon raised had been paid out already to its founders and a few early backers, rather than being used as working capital at Groupon. As a result, the company had more payables due than cash in hand. The filing also revealed that the number of US merchants placing Groupon deals had begun to decline in the second quarter, although the international merchant base continued to grow.

Critics charged that Groupon’s daily-deal model was too easily replicated and would be outdone by competitors such as Google Offers, which launched in April 2011. Others opined that group coupons were a fading fad.

“Groupon is a disaster,” proclaimed Forrester Research analyst Sucharita Mulpuru in one widely circulated article. Meanwhile, the US stock markets tanked in summer 2011 after Standard & Poor’s downgraded the nation’s credit rating, putting the IPO on hold.

In the end, investors turned a deaf ear to the media din, as did Groupon subscribers, who continued to buy. Groupon’s IPO effort survived all the travails, and the company went public in November 2011. The IPO priced at $20 a share, above its planned $16–18 range, raising $700 million in the highest-valuation IPO since Google in 2004.

Where are they now?

At the time of its IPO, Groupon offered more than 33 million deals in a single quarter, to nearly 143 million subscribers in 175 cities across 45 countries. Sixty percent of Groupon’s business is now international.

In early 2010, Eric and Brad co-founded the venture fund LightBank, which focuses on disruptive technology startups. Eric also serves on the boards of several nonprofits. Brad serves on several company and nonprofit boards, and he and Eric teach at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. Andrew continues as CEO of Groupon.

In May 2011, the company introduced Groupon NOW, which enables merchants to implement short-term flash sales. In early 2012, the company reported it was nearing its break-even point.

Connections are key

Founder:

Reid Hoffman

Age of founder:

35

Background:

Technology and product development

Founded in:

2003

Headquarters:

Mountain View, California

Business type:

Professional networking site