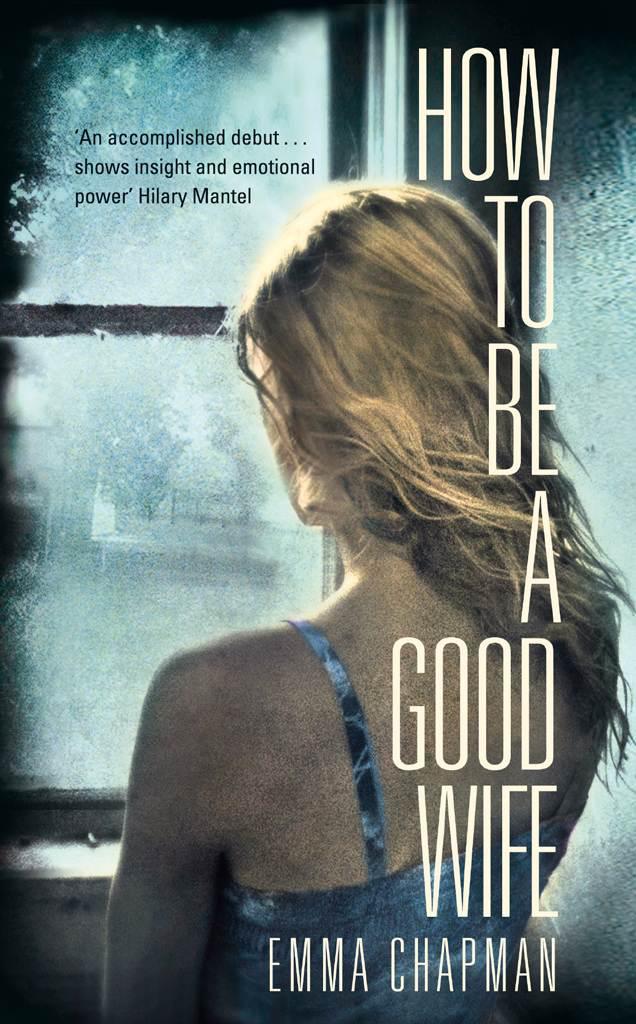

How to Be a Good Wife

Praise for

H

OW

T

O

B

E A

G

OOD

W

IFE

ILARY

M

ANTEL

, Man Booker Prize-winning author of

Wolf Hall

AVID

H

EWSON

, author of

The Killing

LIZABETH

H

AYNES

, author of

Into the Darkest Corner

How To Be a Good Wife

is at once claustrophobic, startling and hauntingly beautiful. It’s that amazing, awful kind of book that will stay with you long after you wish it would let you go’

IZA

K

LAUSSMANN

, author of

Tigers in Red Weather

VIE

W

YLD

, author of

After the Fire, A Still Small Voice

UTH

D

UGDALL

, author of

The Woman Before Me

, winner of the CWA debut dagger award

IMON

L

ELIC

, author of

Rupture

and

The Child Who

YLAND

, Man Booker Prize-shortlisted author of

Carry Me Down

and

This is How

How To Be a Good Wife

in one sitting’

ANE

R

USBRIDGE

, author of

Rook

and

The Devil’s Music

USANNA

J

ONES

, author of

When Nights Were Cold

NDREW

M

OTION

First published 2013 by Picador

This electronic edition published 2013 by Picador

an imprint of Pan Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-1-4472-1620-9 EPUB

Copyright © Emma Chapman 2013

The right of Emma Chapman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Housekeeping ©

Marilynne Robinson and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit

www.picador.com

to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you’re always first to hear about our new releases.

For Kate and Keith Chapman

for teaching me everything I know

‘Come on my history horses!’

‘And below is always the accumulated past, which vanishes but does not vanish, which perishes and remains’

– Marilynne Robinson,

Housekeeping

1

Today, somehow, I am a smoker.

I did not know this about myself. As far as I remember, I have never smoked before.

It feels unnatural, ill-fitting, for a woman of my age: a wife, a mother with a grown-up son, to sit in the middle of the day with a cigarette between her fingers. Hector hates smoking. He always coughs sharply when we walk behind someone smoking on the street, and I imagine his vocal cords rubbing together, moist and pink like chicken flesh.

I rub the small white face of my watch. Twelve fifteen. By this time, I am usually working on something in the kitchen. I must prepare supper for this evening, the recipe book propped open on the stand that Hector bought me for an early wedding anniversary. I must make bread: mix the ingredients in a large bowl, knead it on the cold wooden worktop, watch it rise in the oven. Hector likes to have fresh bread in the mornings.

Make your home a place of peace and order.

The smoke tastes of earth, like the air underground. It moves easily between my mouth and my makeshift ashtray: an antique sugar bowl once given to me by Hector’s mother. The fear of being caught is like a familiar darkness; I breathe it in with the smoke.

I found the cigarette packet in my handbag this morning underneath my purse. It was disorientating, as if it wasn’t my bag after all. There were some cigarettes missing. I wonder if I smoked them. I imagine myself, standing outside the shop in the village, lighting one. It seems ridiculous. I’m vaguely alarmed that I do not know for sure. I know what Hector would say: that I have too much time on my hands, that I need to keep myself busy. That I need to take my medication. Empty nest syndrome, he tells his friends at the pub, his mother. He’s always said I have a vivid imagination.

Outside is a clear circle of light. Hector’s underpants, shirts and trousers move silently in the breeze. Holding the cigarette upright, the glowing tip towards the ceiling, I notice the red-rimmed edges of my fingernails. A shadow shifts across the table. I see a hand, reaching out: the fingers spread open to take it. It is small, with bitten-down nails, a silver ring gleaming on the index finger. Without thinking, I offer the cigarette, but when I look again the hand is gone. The hairs on my arms rise. I turn quickly, my heart beating, but the room is empty.

With a shaking hand, I stub my cigarette against the delicate china and cross the kitchen. Folding a piece of paper towel around the butt, I wrap it with an elastic band, trying to trap the smell. It still emits the stench of stale smoke. Dropping the sugar bowl into the steaming water in the sink, I hide the cigarette packet in the teapot. I put the paper parcel on the window ledge outside the front door. The air is fresh and cold, like plunging my face and chest into ice water. I will dispose of it later, on my way to the market.

I check my watch again. Twelve twenty-five. I set it every day by the clock on the evening news: it is important for me to know the correct time.

Standing at the open front door on the raised porch, I look out at the dirty stretch of lane. Beyond it, the wide green fields spread towards the edge of the rising valley. The clear blue sky opens up above the darkness of the mountains, and as I look up, I feel dizzy.

The tree at the end of our drive is losing its browning leaves: they pool deliciously at its trunk. I long to hear them crunch under my shoes, to run across the valley and through the dark forest until my lungs burn. The cold wind would lash my face, blowing through my hair: my feet would kick up the dirt. I wouldn’t stray from the path.

Holding on to the wooden door, I don’t step outside. At one o’clock, I will go to the market.

Your husband belongs in the outside world. The house is your domain, and your responsibility.

I look at my watch again. Twelve thirty.

Behind the closed front door, it is silent in the house. There is no microwave beeping, no sound of a car door slamming in the drive outside. The washing machine is not even churning: I couldn’t scrape together enough for a wash today. The only sound is my breathing, in and out, in and out. The house is always empty now, except for me and sometimes Hector.

The weak midday light slants across the beige carpet. Kylan smiles down from the various pictures on the walls. His first day at school, standing proudly beside Hector’s car with his socks pulled up and his new blazer over his arm. In skiing goggles, his face pink and lips rubbery around slightly crooked teeth. Several of him as a baby, his hair sticking up unnaturally and the same gummy smile. I miss him: the stiffness in his crying body, his tense screams, and how he would calm when he found himself in my arms. He has forgotten now, but he felt like this once.

There is only one picture of Hector and me together: our wedding photo. We stand in the church doorway, Hector looking straight at the camera, while I smile up at him. He looks like a husband should: strong and protective and content. If I look closely, I can make out the few grey hairs on his head, the lines around his eyes. My white face is startled by the new light of the churchyard: I was just twenty-one, like a child, my body impossibly slender in the narrow wedding dress. I look happy, but I can’t remember if I was. It’s so long ago that a dull fog has fallen, and no matter how I grasp, only a few details remain. The particulars of running the house have taken up the space, replacing the old moments. I have a few: Hector’s rough hand clasping the top of my arm as we walked through the dark church towards the bright square of daylight. And the feeling of exposure: the eyes of the photographer on my face; Hector’s parents standing to one side, watching.

Hector’s mother organized everything: she liked things to be done right, and made it quite clear she thought I was too young to understand. Her wedding present to me had been a book:

How To Be a Good Wife

, which she said would teach me everything I needed to know. I still have it somewhere, old, and well-thumbed. I learnt every page by heart.