How to Become Smarter (30 page)

- Improved attention control can enhance memorization by giving a person enough self-discipline to read a text not just once but several times.

- Good attention function can allow you to understand complex texts, sooner or later, by helping you to read sufficient amounts of introductory material.

[

Previous

][

Next Key Points

]

Studies show that high-protein diets cause some biochemical changes in the brain that are similar to those caused by attention-enhancing drugs, such as

Ritalin

®. In addition, research shows that a restrictive elimination diet, which is devoid of artificial ingredients, benefits patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Therefore, this chapter proposes a high-protein diet that is free of junk food and food additives as a method of improving attention. One possible diet (I call it the “balanced high-protein diet”) consists of boiled meat, poultry, fish, raw nuts, fruits, and vegetables. Another diet, the “modified high-protein diet,” is similar but also includes substantial amounts of raw wheat extract (Appendix I) and pasteurized low-fat dairy. The latter diet has fewer adverse effects than the former.

Several published studies and personal experience of the author suggest that increased intake of high-quality protein, such as meat, improves the ability to concentrate. You can achieve even better results, in particular better reading comprehension, if you simultaneously increase protein intake and eliminate artificial chemicals and junk food from the diet. A reverse approach, almost complete elimination of protein from the diet (for example, a fruit-and-vegetable diet) reproduces most symptoms of ADHD: distractibility, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. You can reverse these symptoms if you add protein-rich foods back to the diet.

Several studies suggest that ADHD patients exhibit signs of low consumption of dietary protein. These signs include a somewhat smaller brain size in ADHD children compared to their peers and lowered levels of total protein and some amino acids in blood.

[

Previous

][

Next Chapter Summary

]

- The concept of emotional intelligence

- Treatments that may reduce or increase emotional sensitivity

- Why high consumption of cooked meat and cooked grains can cause symptoms of depression

- The “antidepressant diet,” or why a safe raw high-protein diet can improve mood

- Lifestyle changes that reduce anxiety

- A lifestyle that can cause hypomania and boost creativity

- Is constantly elevated mood desirable?

- A possible anger management protocol

- Summary of Chapter Four

As we saw in Chapter One, there are types of intelligence different from academic intelligence, also known as “intelligence” or IQ. Just to remind you, academic intelligence includes mental abilities related to understanding and manipulation of words, numbers as well as geometrical shapes of objects and spatial relationships among them. The other two more or less validated types of intelligence are emotional intelligence and social intelligence. Social intelligence is the ability to understand and behave intelligently in social relationships and we will talk about it in Chapter Six. It is possible that there are additional types of intelligence, for instance, practical intelligence and spatial intelligence. This topic is outside the scope of this book.

According to the researchers who formulated this scientific concept, emotional intelligence is “the ability to carry out accurate reasoning about emotions and the ability to use emotions and emotional knowledge to enhance thought” [

23

]. These psychologists, John Mayer and Peter Salovey, have devised a model of emotional intelligence that combines abilities from four related areas: (a) accurately perceiving emotion, (b) using emotions to facilitate thought, (c) understanding emotion, and (d) managing emotion. To avoid ambiguity, we will use the following definition of an emotion: “an integrated feeling state involving physiological changes, motor-preparedness, cognitions about action, and inner experiences that emerges from an appraisal of the self or situation” [

23

]. Both the definition of emotions and the concept of emotional intelligence are not without controversy in the field of psychology. There are different models and definitions, advocated by different authors [

434

-

439

]. At present, many researchers view the model developed by Mayer and Salovey as the best-validated model of emotional intelligence. The initial enthusiasm and hype related to emotional intelligence in the 1990s have subsided by now. Many preliminary claims and assumptions made by other authors turned out to be incorrect. In particular, later studies have shown that emotional intelligence does not predict academic performance and job performance better than IQ. Some studies have even shown that emotional intelligence does not predict them at all. At this point, it is safe to say that the IQ is still relevant, whereas emotional intelligence has some unresolved issues and needs further validation. For example, there are competing definitions and models of emotional intelligence, and different tests of emotional intelligence show poor correlation among themselves. It is still unclear how one should measure certain components of emotional intelligence [

23

]. This is not the case with academic intelligence and IQ tests. Readers can find a good critical overview of emotional intelligence research in these sources: [

440

-

442

].

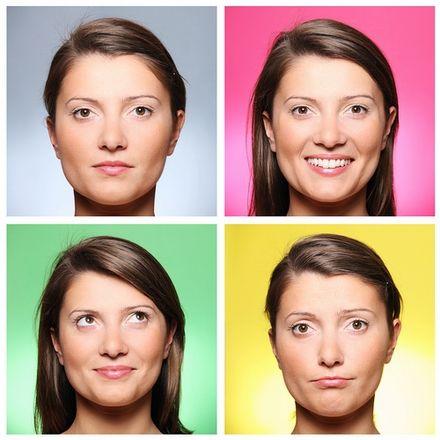

The MSCEIT (Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test) is thought to be the best-validated test of emotional intelligence, although it is not perfect. For example, the ability to perceive emotions of other people, as measured by the MSCEIT, does not correlate well with this ability as assessed by other well-designed tests [

23

,

435

,

436

]. Here is how the MSCEIT test works [

23

]: trained technicians administer the test, which consists of a series of multiple-choice questions, some of which contain pictures. The test contains 141 questions distributed among eight tasks. Each task assesses a different component of emotional intelligence: (1) emotional perception in faces and (2) in landscapes; using emotions (3) with objects not normally associated with emotions and (4) in facilitating thought; (5) understanding emotional changes across time and (6) blends; (7) managing emotions in oneself and (8) in relationships. The MSCEIT test produces the score for overall emotional intelligence as well as four subscales: perceiving, facilitating, understanding, and managing emotions.

There are a number of other tests of emotional intelligence. Some of these tests consist of self-rating questionnaires [

434

,

443

]. Research shows that this self-assessment produces results that are different from the results of more objective tests, such as the MSCEIT [

444

]. If different tests show divergent results, we can assume that many of the existing tests measure something other than emotional intelligence, for example, personality traits or psychological well-being. Consequently, readers need to exercise caution when interpreting findings about possible real-world applications of emotional intelligence testing. Even the best-validated tests still have unresolved issues, as discussed above.

Preliminary findings suggest that there may be a weak-to-moderate correlation of emotional intelligence scores with the following life outcomes [

23

]:

- better social relations for children and adults;

- better family and intimate relationships;

- higher academic achievement (academic degrees) but not better grades;

- better psychological well-being.

Some studies did not find these correlations and further research is needed. Additionally, there may be some overlap between the abilities related to social intelligence and those related to emotional intelligence [

31

]. In contrast to academic and social intelligence, it seems impossible, at present, to distinguish the crystallized and fluid components of emotional intelligence by means of existing tests. Most tests, including the MSCEIT, assess crystallized emotional intelligence, that is, knowledge and skills related to emotions [

445

]. Since one can acquire knowledge and skills, it is possible that emotional intelligence will improve as a result of special training [

23

]. Further research is needed in this area.

In conclusion, the research of emotional intelligence is a growing and promising field. Tests of emotional intelligence await further validation and resolution of inconsistencies. Some self-rating tests are available free of charge [

443

]. When interpreting the results of self-rating tests please keep in mind the limitations discussed above. The mental clarity questionnaire presented in this book (

Appendix IV

) is designed to assess some components of emotional intelligence. The number of questions, however, is too small and this test does not provide a separate score of emotional intelligence.

The sections that follow describe techniques that may improve some components of emotional intelligence. We will talk about management of internal mood, suppression of undesirable emotions such as anger and resentment, and regulation of sensitivity to emotions of other people. For the above reasons, this book cannot supply readers with an instrument for measuring improvements in emotional intelligence. Nonetheless, an honest assessment of the effectiveness of my advice is still possible. For example, if you find the creativity regimen to be effective (the section “A lifestyle that can cause hypomania and boost creativity”), this means that you can gain greater control over your emotional state. If the anger management protocol (last section of this chapter) does not prevent fits of anger, you can conclude that this method does nothing for your emotional intelligence.

- Emotional intelligence is thought to encompass abilities from four areas: (a) accurately perceiving emotion, (b) using emotions to facilitate thought, (c) understanding emotion, and (d) managing emotion.

- The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) is probably the best-validated test of emotional intelligence to date.

- The field of emotional intelligence research still has some unresolved issues, such as the lack of consensus on definitions and low correlation among different tests.

[

Previous

][

Next Key Points

]

One of the components of the emotional intelligence model of Mayer and Salovey is the ability to perceive other people’s emotions accurately. There are several well-designed tests of accuracy of perception of emotions, but they do not correlate well among each other. The reason for this lack of correlation is unknown [

23

]. There is a similar concept, which is related to perception of emotions, which I call

emotional sensitivity

. This chapter defines that term as the ability to pay attention to the emotions of other people and willingness to foresee emotional responses of other people to one’s actions. As you can see, emotional sensitivity is related to two components of the Mayer and Salovey model: perception and understanding of emotion. Yet emotional sensitivity as defined above also includes the component of interest in (or indifference to) other people’s emotions. Most people can accurately perceive and understand others’ emotions, but an emotionally sensitive person is also interested in (or unable to ignore) other people’s emotions. An

emotionally insensitive

person is indifferent to (or able to ignore) others’ emotions. The word “sensitivity” in English has an additional meaning: the propensity to take offense. For simplicity’s sake, we will assume that “emotional sensitivity” only deals with perception of emotions of other people and does not have the additional meaning in the context of this chapter.